According to a recent news report, the waste pickers in the city of Guntur, in coastal Andhra Pradesh, live in grim conditions right inside the city dump. The story was first published in mid-September and the Global Alliance of Waste Pickers website subsequently provided a link to it.

The story is reminiscent, on a much smaller scale, of the one told in Behind the Beautiful Forevers, Katherine Boo’s entrancing bestseller about a vast slum near the Mumbai airport and the people who live there. But unlike the waste pickers in many other Indian cities, the residents of this slum are all Yanadis.

The story is reminiscent, on a much smaller scale, of the one told in Behind the Beautiful Forevers, Katherine Boo’s entrancing bestseller about a vast slum near the Mumbai airport and the people who live there. But unlike the waste pickers in many other Indian cities, the residents of this slum are all Yanadis.

The author, Kabir Khan, visited the area of coastal Andhra Pradesh in southern India between the cities of Guntur and Vijayawada at the invitation of a group that is working on land rights issues for oppressed peoples. The group, the Dalit Bahujan Resource Center (DBRC), decided last year to become involved with the waste pickers of the two cities.

Kabir provides useful background. He indicates that the state of Andhra Pradesh, which was separated from the new state of Telangana in June 2014, needs to designate a new capital city since Bangalore, its former capital, will remain the capital of the new state. Andhra Pradesh, the author indicates, has chosen the area between the two small cities (small in Indian terms—less than a million inhabitants) to be the location of its new capital, which will probably grow rapidly. While the city dump of the new metropolis will doubtless not come close to the size of the one for the city of Mumbai, the needs of the people living off the garbage—the Yanadi—should be cared for.

The Guntur dump occupies 72 acres of land and receives about 310 metric tons of garbage per day. Comparing data from the city and from other studies, the author argues that roughly 68.5 percent of the waste is organic, 10.5 percent is reject and sanitary, and 21 percent is recyclable. The city dump has 1,000 waste pickers living on the income that they can derive from their informal economy: salvaging and recycling items from that 21 percent.

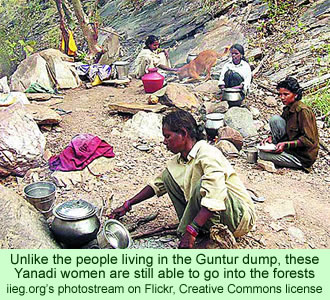

Kabir reviews the background of the Yanadi effectively. He writes that they used to be nomadic forest dwelling people, but they subsequently settled in coastal districts of Nellore and Chittoor, where they became experts in assisting farmers in such occupations as catching snakes and harvesting rats. A news story five years ago describes their continuing occupation—providing rat control in one community. Changing times have prompted some of them living in the Guntur area to change their vocations again, though now their circumstances are worse, the author writes.

The author met waste pickers in the dump area during his visit. He asked them about their traditional vocations and they all replied firmly that they had been waste pickers as long as they could remember. They had been scavenging at an old dump in Guntur, but when it was closed, they moved to the new one. They live a few feet away from the mountains of trash and garbage they search through. They live in temporary huts made primarily of palm leaves on land owned by the government.

Most of the Yanadi the author interviewed had no identity cards except for a few who had obtained their Aadhaar Cards, unique identification documents issued by the Indian government, though those people didn’t know how to use them to obtain benefits. Only one person, Tummalankamma, had a ration card, but it didn’t do her any good since the Public Distribution System shop was too far away.

She told Kabir that she had recently applied for her national identity card, but she didn’t know anything more about it. The author found that the waste pickers can earn only about INR 500 per week, about US $1.00 per day, on which they have to feed their families.

The author saw many children along with their parents in the large dump area. The children generally don’t get much if any education since the school provided by the government is too far from where they live. However, a small church in the immediate neighborhood has started offering classes on a daily basis; the pastor is trying to persuade the Yanadi to send their children to school. The problem for parents is that their children are needed to help pick through the rubbish to find materials to sell.

The pastor, Manik Rao, told the writer that the government had threatened to shut down the more distant public school because few children were attending. To prevent that, he agreed to send the children attending the school in his church to the government school instead. Srinivas, a leader in the local community, has agreed to sponsor the transportation of the children to the public school.

The DBRC, the organization that is championing the Yanadi waste pickers, is opposing the construction of a waste incineration plant for the area. The plans, formulated by a team of engineers from Singapore, were announced in the Indian media about four months ago. The proposed plant will replace the recycling efforts of the poverty stricken Yanadi, and they will have nowhere else to go for income, Kabir predicts. The amount proposed for the large incineration plant could be better spent on safety equipment for the Yanadi, better pay for their work, and effective food, health, and social networks for them, he argues.