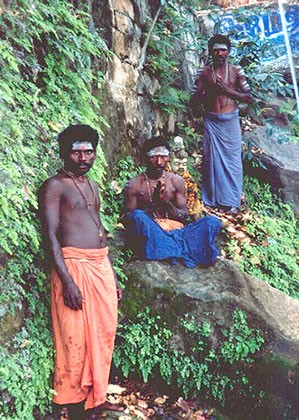

Location. Nearly 5,000 Paliyans live in the forested hills of western Tamil Nadu state in southern India and in villages in the nearby plains. Gardner (2000b) studied Paliyan conflicts, and the resolution strategies they employ, in numerous settlements in the forested mountains and in the plains villages, especially in one village at the edge of the mountains that he called Cempaka Tooppu, near the town of Srivilliputtur. Cempaka Tooppu is now called Shenbagathoppu (with various spellings). It is still a Paliyan village and is a major entry point for the enormous Shenbagathoppu Grizzled Squirrel Wildlife Sanctuary. The 2001 Census of India lists the people variously as Palleyan, Palliyan, or Palliyar.

Economy. Some Paliyans still subsist on gathering food and other products in the forests, which they supplement with wage labor for plantations and farms in the nearby valleys. Many have settled in the plains and have taken up farming near their Tamil neighbors. Some of the people who live in Shenbagathoppu have jobs helping care for the endangered giant grizzled squirrels in the Grizzled Squirrel Wildlife Sanctuary. The economies of some of the Paliyan families depend, in part, on bartering forest produce such as honey for manufactured goods such as tools, pots, clothing, and ornaments. Gathering honey from wild bee colonies remains an important economic resource—and cultural inspiration—for the Paliyans. They also continue to gather and use wild plants from the forests, particularly for their medicinal values. However, many of them live in poverty and are exploited by nearby Tamils. In 2015, forestry officials in Tamil Nadu trained 16 Paliyan youths as trekking guides in the mountains near their settlement.

Beliefs that Foster Peacefulness. The Paliyans have a very atomistic, anarchistic society, with each individual making his or her own decisions. They have a strong desire for autonomy, which shows up in their psychological structures. They refrain from forming emotional ties except within their nuclear families. Ties with other relatives will be friendly but not effusive. They emphasize their autonomy through their code of nonviolence—and they will express their belief that one should turn the other cheek if one is struck in the face. A blog post in 2012 indicated proudly that the peaceful structures still persist in their society, though they are threatened by corrupt outsiders. A different Paliyan blog post indicates that while they cherish their traditions, many adapt to modernity and are settling into stable village life.

Avoiding and Resolving Conflict. The Paliyans maintain order and resolve conflicts through the use of several control mechanisms.

- Self-restraint. One mechanism is self-restraint, repression of anger, and suppression of hostile feelings. In order to help achieve this, they avoid the consumption of alcohol, which they feel would make them aggressive.

- Dissipation of anger. They also dissipate anger by pressing a plant called sirupani pu, or “laughing flower,” to their foreheads. They sometimes redirect their feelings of aggression through dreams, fantasies, and watching violent films.

- Intervention. Community leaders may sometimes intervene in conflicts and attempt to conciliate through joking or soothing.

- Separation. If other methods fail, the parties to a dispute will separate. Villagers may move away or form new villages to avoid disputes. Normally the injured person or group feels the obligation to withdraw, to avoid the danger of retaliation.

- Supernatural. Another conflict resolution mechanism is the belief in supernatural forces—people fear that conflict might prompt revenge through sorcery. This prompts circumspect behavior.

Gender Relations. Paliyans prefer to be married, frequently with simple ceremonies that involve exchanging vows of fidelity for life. The ceremonies include exchanges of salt and betel leaves. Conflicts, however, cause spouses to terminate their marriages quickly, so while some marriages really are for life, most Paliyans marry one person after another, ending each union when a dispute arises. Neither spouse has authority over the other; they both have equal rights and independence. Nuclear families usually cooperate as social units, though there is no division of labor between the sexes. The Paliyans are so atomistic that some married people, at times, do not even share their food for months, though they continue to cooperate in feeding their children.

Raising Children. Paliyan parents indulge their infants constantly. Babies sleep next to the mothers, who give them their breasts at the slightest whimper. They are not disciplined, restrained, or punished.

- Achieving Emotional Independence. Mothers wean their children when they are between two and two and one half. This is a traumatic period for children since the mothers will start leaving them with relatives in the village in order to go back to work. Also, for the first time, the children may receive their first mild punishments and the mothers will stop responding immediately to their demands. Children become extremely angry and frequently cry for extended periods, though relatives may sometimes comfort them. The tantrums normally last until the children are four or five years old. The emotional independence that results prompts children to adhere to the social rules, to play quietly without fighting, to be reticent, self-confident, and socially skilled.

- Achieving Social Independence. Between eight and ten years of age children achieve social independence and are considered to be too old to be under the authority of their parents, though they usually do not achieve their full economic independence until thirteen or fourteen.

Social Practices. The Paliyans are very quick to flee from a situation—even to abandon their villages—if they perceive that a threatening situation is developing.

- Example 1. When a contractor killed three Paliyans, the remaining villagers immediately left for the forest. Five years later, as they were slowly moving back toward the frontier zone between the mountains and the farmlands, they were quite willing to be interviewed by anthropologist Peter Gardner on other subjects, but they would still not discuss the violent incident.

- Example 2. When Gardner, dressed in what looked like khaki clothing, appeared in a Paliyan settlement one day among people he already knew, they quietly began gathering their few belongings and leaving. In 20 minutes everyone was gone. He speculates that his clothing may have reminded them of an incident of police brutality a few weeks before. They didn’t return to the area for three months.

Cooperation and Competition. The Paliyans extend their injunction against violence to a prohibition of competition, which arises, they feel, from rivalries and desires for superiority or control. They feel competition leads to social disharmony and threatens self-reliance and egalitarianism. Since they expect to be self-sufficient, individualistic, and socially anarchistic, they also don’t cooperate much. They disapprove of any behavior that appears, to them, to hamper the autonomy of an individual, such as cooperation or competition. Such behavior is disrespectful—or, in their terms, it appears to lower someone’s status.

Cooperation and Competition. The Paliyans extend their injunction against violence to a prohibition of competition, which arises, they feel, from rivalries and desires for superiority or control. They feel competition leads to social disharmony and threatens self-reliance and egalitarianism. Since they expect to be self-sufficient, individualistic, and socially anarchistic, they also don’t cooperate much. They disapprove of any behavior that appears, to them, to hamper the autonomy of an individual, such as cooperation or competition. Such behavior is disrespectful—or, in their terms, it appears to lower someone’s status.

Strategies for Avoiding Warfare and Violence. In order to avoid, as much as possible, any semblances of conflict or violence in their frontier settlements, the Paliyans maintain a humble, self-effacing manner in their contacts with outsiders. However, they are learning the power of nonviolent active protests from Indian followers of Gandhi.

But How Much Violence Do They Really Experience? The forest-dwelling Paliyans will do almost anything to avoid violence or even conflicts. The ones that have lived in the settled villages and been influenced by the majority Tamil peoples of South India for as much as 150 years do experience occasional violence. Even so, physical violence occurs in very mild forms, such as parents giving an obstreperous child a gentle slap on the buttocks on occasion.

Scholarly Resources in this Website:

- “Pragmatic Meanings of Possession in Paliyan Shamanism.” (Gardner, 1991)

- “Respect and Nonviolence among Recently Sedentary Paliyan Foragers.” (Gardner, 2000)

More Resources in this Website:

- A Paliyan man complained on Facebook about being ignored by a government official and he received an immediate response. It took over a year and a half but ultimately the government came through with new housing for the Paliyan colony.

- Some Paliyans help care for baby giant grizzled squirrels, endangered animals which live in a forest reserve near their village.

- Paliyans eagerly voted in the Indian national elections in 2014.

Sources in Print: Gardner 1966, 1969, 1972, 1985, 2000a, 2000b, 2004

Sources on the Web: Collective Action for Forest Adivasi in Tamil Nadu (CAFAT); Paliyar Tribal Empowerment; Wikipedia (English Version)

Updates—News and Reviews:

Selected Recent Stories

August 20, 2015. Paliyan and Kadar Dances

November 7, 2013. Avoiding Conflicts in South Asia [anthology chapter review]

January 31, 2013. Flowering Plants, Tamil Poetry, and the Paliyans

October 18, 2012. Peace March Ends; Paliyans Head Home

All Stories

All stories in this website about the Paliyan are listed in the News and Reviews Subject Listing