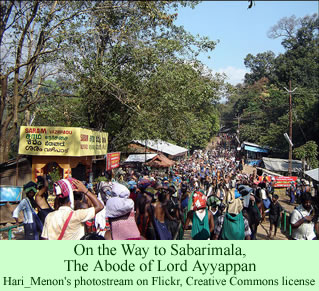

During the annual pilgrimage season which just ended, more than 30 million Hindu devotees visited the temple of Lord Ayyappan at Sabarimala, India, almost without incident, the Times of India reported on Friday. One source points out that the Hindu rituals at the Ayyappan temples, in the forested hills of Kerala state, represent the largest pilgrimage in the world.

But just as the Times of India filed its story, disaster struck. Reports differ, as with any epic tragedy. One news story said that a vehicle crashed into a crowd of devotees, setting off a stampede which resulted in over 100 people being trampled to death. Other news sources indicated that a jeep traveling on a forest path hit an auto-rickshaw, which overturned, sparking the stampede. In either case, large numbers of people were injured and killed. The accident occurred on a path which leads out of the hills of Kerala, down toward the plains of Tamil Nadu.

But just as the Times of India filed its story, disaster struck. Reports differ, as with any epic tragedy. One news story said that a vehicle crashed into a crowd of devotees, setting off a stampede which resulted in over 100 people being trampled to death. Other news sources indicated that a jeep traveling on a forest path hit an auto-rickshaw, which overturned, sparking the stampede. In either case, large numbers of people were injured and killed. The accident occurred on a path which leads out of the hills of Kerala, down toward the plains of Tamil Nadu.

The Malapandaram live in the same forests as the Ayyappan temples—in close proximity to them, in fact. The tragedy prompts a closer look to see if they might have been involved. To judge by the literature, it is unlikely.

For one thing, the Malapandaram would not have been walking back along a pathway toward the plains. More to the point, they don’t get involved with Hindu religious festivals. They have very different religious and spiritual beliefs from the Hindu pilgrims who visit the Ayyappan temples in their midst.

Brian Morris (1992) describes the differences between the religious beliefs of the Malapandaram and the Hindus. The Malapandaram believe in hill spirits, supernatural beings associated with particular hills or landscape features. There are many of them. They identify one hill spirit for every 8 square kilometers of forested land, Morris estimates. They also believe in ancestral shades, spirits which generally have beneficent intentions, protect the people against misfortunes, and offer advice when needed.

Morris (1981) goes into greater detail about the Ayyappan cult in the hills of Kerala and the religious practices of the nearby Malapandaram. There are four major Ayyappan temples, he writes. Kulathupuzha and Arienkavu are holy sites associated with the deity when he was a youth. Achencoil is where he hunted as a young male god. In this area, Ayyappan had, in the words of Morris, “amorous affairs with two particular young women (p.222).” Sabarimala, where the tragedy occurred this weekend, is the major Ayyappan temple, one built by a local king at the request of the god himself.

The anthropologist explains that although the Malapandaram describe themselves as Hindus when outsiders ask them about their beliefs, they really are not. Morris spent some time doing field research among the Malapandaram in the immediate vicinity of Achencoil, which is located about 20 miles south of Sabarimala. He explains that while the Malapandaram trade with the Hindus at Achencoil, they have little interest in their religious beliefs, myths, or deities.

The Malapandaram only recognize Ayyappan, and his associated deity, Karuppaswami, in a peripheral fashion. They have minimal knowledge of these two locally-venerated gods and they know almost nothing about the nationally recognized deities of the Hindus. They visit the Ayyappan temples during the pilgrimage season, November through January, only for secular purposes.

The primary difference between the minority population and the Hindus is that the hill people contact their spirits through trances and possession rituals, Morris explains. They have no shrines or temples and, unlike the Hindus who attend the Ayyappan pilgrimage in order to make personal appeals to the god, they have no interest in propitiating any spirits. Furthermore, unlike Hindus, they have no use for regular ceremonies or formal rituals, they do not observe religious periods or dates, and they do not venerate sacred spots.

Unlike the Hindu Brahmins, they do not allow any hierarchical relationships to develop between their ritual specialists and the rest of the community. The caste system of the Hindus is absent in Malapandaram society.

Morris (1981) observes that some other South Indian tribal societies, such as the Paliyan and the Kadar, have become more integrated into the lives of the surrounding Hindu people than the Malapandaram. As a result, their religious beliefs and practices have adopted some of the trappings of the wider society.

For example, the Paliyan and Kadar, increasingly, have begun to represent their deities in the form of icons. Also, they are adopting propitiatory rites, practices derived from the Hindus that the Malapandaram so far (as of 1981, at least), have not adopted. The Malapandaram remain quite distinct from the Hindus, so their religious practices show little Hindu influence.

Furthermore, as people from the plains have moved into the hills, primarily as workers in forest extractive industries, they have begun to adopt the Malapandaram spirits and imbue them with their own religious values. Outcroppings in the hills, associated by the Malapandaram with spirits, have been adopted by these people from the plains as deities. They have begun marking the rock outcroppings with stone piles or other iconic markers.

As part of their veneration, the forest workers have left groves of large trees standing around these sites to mark their sacredness. The workers may stop and salute the stone piles as they walk past them, or light incense sticks in front of them. The Malapandaram dismiss this veneration and are irreverent toward these places.

A much more recent account by Morris (1999) adds some brief details to our knowledge of Malapandaram religious practices. He writes that their interactions with the mountain sprits normally include prayer and meditation, offerings of betel leaves and honey, and possession rites.

Their ritual specialists, called Tullak-aran/i, are men or women who go into dance-induced trances, accompanied by drumming and singing, in order to be possessed by a deity. They handle misfortunes and crises, such as illnesses or hunting problems, during their trances. Their ritual specialists do not act as mediators between individuals and their gods.

While the Malapandaram doubtless were not involved in the pilgrimage fervor, the tragedy this weekend serves as a reminder that small, peaceful societies can exist in the midst of the vast Indian ferment, but still retain their distinct identities and beliefs.