While most of the literature about Ladakhi peacefulness focuses on India’s Leh District, the primarily Buddhist portion of Ladakh, the Muslim district called Kargil after its principal town appears to have a culture that is just as nonviolent.

The two districts are populated with basically the same people who have many similar customs. They differ in that most of the inhabitants in the Kargil District, the northwestern part of Ladakh, converted to Shi’a Islam in the 16th century, while the southeastern portion closer to Tibet, the Leh District, remained primarily Buddhist.

The two districts are populated with basically the same people who have many similar customs. They differ in that most of the inhabitants in the Kargil District, the northwestern part of Ladakh, converted to Shi’a Islam in the 16th century, while the southeastern portion closer to Tibet, the Leh District, remained primarily Buddhist.

Several worthwhile articles appeared in major Indian newspapers last week which focused on Kargil, the less famous district. One story described a new film festival being held in Kargil this coming weekend, May 19 and 20. The Awam ka Cinema, which allows free admission for viewers, will offer films in three categories: documentaries, short fiction, and animated shorts.

According to an entry on a Yahoo groups message board, the first Kargil Film Festival will follow the same goals of peace and brotherhood as the earlier Indian film festivals the organizers have held, starting in Ayodhya in 2006. The organizers write that they hope to inspire “social and cultural change” in their country.

“The main motive behind this initiative,” the message states, “has been to create a dialogue between people from different sections of society and country through the medium of art and cinema. This will open up a platform for people to express, share and understand each others’ joys and sorrows, situation[s] and condition[s] in life, a platform that will have infinite space for humanity. In an age and time when the pillars of democracy such as the parliament, legislature and even the media are ambitious about money rather than for the genuine issues of the people, the only hope for the people to develop cultural unity is through such efforts.”

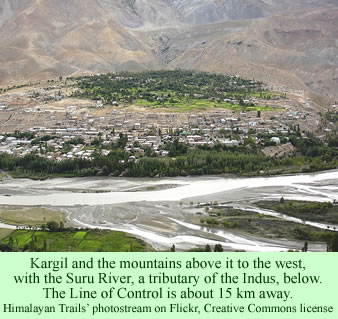

Others consider the problems of Kargil in different ways. The Daily Pioneer, an English language paper, carried an article last week examining the effects of the Line of Control, the cease fire line partitioning India and Pakistan, on the divided peoples in Ladakh, especially Kargil. The division has caused constant conflicts between the two nations and a lot of internal strife among the local citizens.

The partition divided Kargil from the mostly Muslim peoples of northern Pakistan, which used to also be part of Ladakh. Skardu, the major town in what is known as Baltistan, is north northwest from Kargil, down the Indus River valley a distance of 173 km. Driving over the mountains by way of Srinagar and crossing into Pakistan, then northeast to Skardu, is a distance of 1,700 km. In essence, the same Ladakhi people are divided by the militaries of the two countries along the Line of Control.

The argument made by the author of the piece, Zainab Akhter, is that a restored road along the Indus River could become an important trade and tourism route, which would be open 12 months of the year. Adventure tourism, trekking, mountain biking, river rafting, and high altitude mountain skiing all could develop in the region if a good road were open and safe for travel.

Akhter writes that the Hill Development Council in Kargil strongly favors the concept of a Greater Ladakh, the historic approach to the region, which would include Kargil, Baltistan, Skardu, and even Gilgit, still farther to the northwest in Pakistan. Akhter, a research scholar with the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies in New Delhi, argues that opening up the border in the region might begin to pacify, if not to really solve, the Kashmir conflict.

A third article last week in The Hindu, one of India’s major papers, describes in more detail the history of the Kargil District, which was carved out from the Leh District in 1979. The author argues that the problems of the inhabitants do not receive much attention from the rest of India. The people are mostly farmers who keep livestock, the same as rural folks in the Leh District. But it is a poor region, with inadequate infrastructure.

A tunnel is under construction, which will transform the Srinagar-Kargil highway into a 12 month route across the Himalayas. The highway over the Zoji-La, a high pass over the Himalaya Range, is now closed during the winter due to heavy snow. Opening a better road into the district will permit the development of tourism, which has transformed the Leh District. Leh has an airport but Kargil does not. The high mountains, which suggest the possibility of snow sports, are barriers to any economic benefits from Kargil’s winter weather.

The very word “Kargil,” to many Indians, brings back bad memories of the Kargil War of 1999, according to a fourth newspaper article last week. During that war, the Pakistan Army advanced to a position in the mountains directly overlooking the town of Kargil. Their military forces were able to fire down onto Indian troops moving along the highway below. The author of that article interviewed a press photographer who had been assigned to get photos of the war to send to the Indian media back in 1999.

He took as many pictures as Indian army officers would allow, then hurried over the Zoji-La and into Srinagar to process and forward them to the Indian press. He expressed a sense of pride in his ability to record the events of the war, but he was very disturbed by the casualties. “I saw wounded Army personnel; some did not have hands, some had lost legs. It was a very, very sad sight,” the photographer reminisced.

While none of the four newspaper articles directly discuss the peacefulness of the Ladakhi people of Kargil, they all, in various ways, suggest the hope—the possibility—that peace can come to this less known section of Ladakh.