Early last week some people in Ohio organized a wild weekend party in a farm field that was attended by about 1,000 Amish youngsters, of whom 73 were arrested for underage drinking. One news story reported that over 40 police officers converged on the field in Hardy Township, west of Millersburg in Holmes County, Ohio, on Saturday the 3rd in response to reports coming into the county sheriff’s office.

Police officials said that of the 73 people arrested, 35 were juveniles. Some were charged with resisting arrest and a few were taken to a hospital for alcohol-related problems. The Millersburg police assisted deputies from Holmes and numerous surrounding counties in rounding up the Amish people and transporting them to the county jail.

According to another news report, Holmes county Sheriff Tim Zimmerly said that it was a record-setting bust. A video accompanying that news report, filmed a couple days after the party, showed lots of trash still littering the out-of-the-way field owned by one Clarence White. Mr. White said that he has been renting his field to the Amish kids for parties as part of their well-known “rumspringa” activities for 12 years.

Years ago, he said, the Amish young people ordained him as “the party pope.” He charges them $20 per person, which brought in $20,000 for the 1,000 who attended. Expenses came to $15,000 for bands, tents, and portable toilets for the event, he told the reporter. He said he is opposed to underage drinking, and that plenty of people who attended were over 21, the minimum legal age for consuming alcohol in Ohio. But he was candid: “There was a lot of alcohol being consumed here.”

Mr. White said that there was a sign posted warning attendees that the county sheriff would be monitoring the party for illegal drugs and underage drinking. He said he was irritated that some of the kids who were arrested had not touched a drop. In fact, he concluded, “The parents pull in and drop their kids off, because they know they’re going to be safe.”

A different news report indicated that the organizers of the party had rented the property from Mr. White and had charged $25 per person. Mr. White had provided security for the event, but he said the organizers did not ask him to verify the ages of people attending. He insisted that he was providing a service by keeping the Amish kids off the roads at the party on his farm. “It gives them a safe place. They’re not out in the road, and everybody knows they’re going to party,” he said. “They like to drink their beer and everything, so they’re going to party.”

Others disagree. Capt. Doug Hunter in the county sheriff’s office said he is working with the leaders of the Amish settlement to try and prevent their young people from engaging in the rumspringa partying, “but it’s been kind of a heritage with the Amish to go out and do this kind of thing.”

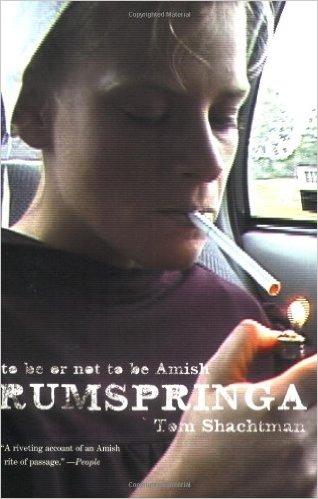

He was right of course. The practice of allowing their youth to run wild in their later teenage years—rumspringa—has gotten a lot of press, and many books on the Amish touch on the tradition. Two published about 10 years ago covered the practice in considerable detail. One, by Tom Shachtman (2006), explained that “rumspringa” simply means “running around.” It’s a simple concept, practiced especially in the larger Amish settlements of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, Holmes County Ohio, and northern Indiana.

Starting at about age 16, the Amish young people in those settlements want to try living more or less like the people in the majority American society. The rumspringa period usually lasts for several years. When the young people reach adulthood, they normally choose to either baptize into the church and become life-long, committed Amish adults, or they drop out and join the “English” society, the majority culture, with all its advantages and disadvantages. Most make the first choice.

A prominent part of that running around period in their lives is the partying in back corners of farms. Shachtman related how a young Amish woman told him how much she enjoyed partying with several hundred other kids, with lots of loud music, smoking, and drinking. Everybody, she told him, was “having a great old time.” This website reviewed the Shachtman book in 2006.

A book by Richard Stevick (2007) further fleshed out the rumspringa period enjoyed by many Amish teenagers. Stevick wrote that the Amish often idealize the activities of their young people, who usually join their elders every other Sunday in the three-hours long worship services held in the home or barn of one of the farms in the church district. The boys and girls will dress exactly as their fathers and mothers do. They will join in the singing from the Ausbund, the book of traditional hymns, and sit quietly during the lengthy sermons. Afterwards, they may go hiking, play games, or join their friends in other activities until the evening supper is ready. After that, they will often join together in the Sunday evening youth singing.

But the reality, in the larger settlements particularly, may be quite different. Beginning on Saturday night, many Amish young people, most changed out of their traditional clothing, hang out around convenience stores and other urbanized locations, waiting for the wild parties to begin in the back corners of fields or the edges of woodlands. Their parties may last until 3:00 or 4:00 am, hindering many from attending church services on Sunday morning. While this second scenario, like the idealized first one, only represents a portion of the young people in the large settlements, both scenarios are part of the changes that Amish youth look forward to when they turn 16, Stevick argues.

A review of the Stevick book in this website pointed out that Amish parents encourage their teenagers “to find out for themselves what the world is all about.” The parents fervently hope their children will remain in the fold and baptize into the faith as adults. They will earn respect when their sons and daughters do so, and they will lose status if they don’t. Even grandparents may feel a sense of shame in some Amish districts if a grandchild decides to leave. Most, however, reject the ways of the broader society and stay.

The process seems to strengthen the Amish society because of the way it prompts commitments by most of their young people to their basic beliefs and to an acceptance of the rules of their group. Uncomfortable as rumspringa may be for Captain Hunter in the county sheriff’s office, it is clearly a successful strategy for the Amish to follow.