Many Mbuti in the eastern D.R. Congo, particularly those living north of Goma near the Virunga National Park, survive by growing and selling marijuana. Last week the National Geographic published on their website a lengthy piece on the story, complete with many interesting photographs.

Twice a week, Nina Strochlic wrote, a group of Mbuti from a village located an hour from Goma get up at dawn to hike three hours up into the forests of the national park. The summit of the volcano Nyiragongo loomed above them as they illegally entered the forest. A dozen people in the group gathered medicinal plants, potatoes, and honey. One member of the party was after marijuana, both the plants and their seeds, since stocks in the village were getting low. The plants are cultivated in the park and they also grow there wild.

The Mbuti take the marijuana plants back to their village where they dry them in the sun to either sell or to use as medicine. Much like reports from the same area of Virunga last year, this National Geographic investigation emphasized the way the park guards hassle, arrest, beat, and even torture the people when they gather plant products in the forest from which they were expelled over 60 years ago when the national park was created.

The Mbuti chief of the village, Mubawa, said that members of his community had been arrested and even killed by the park rangers. Compared to many other protected areas in Africa, however, Virunga is often cited as a park that successfully achieves at least some of its sustainable conservation goals. The famed mountain gorillas are prime attractions for tourists. A community development program, the Virunga Alliance, is a major employer in the region.

The Chief Warden of the park, Emmanuel de Merode, said to the Geographic his administration believes that, for the Mbuti, “the community’s sense of alienation [is] a major problem in terms of environmental and social justice.” He told the reporter that sometimes park rangers have even accompanied the indigenous people on their foraging trips into the park. Mr. de Merode said that, on the whole, park rangers arrest about 20 people per week. He could not recall any arrests, much less killings, of Mbuti.

For their part, the Mbuti told the Geographic that they have been harvesting marijuana in the forests of the mountain range for a very long time. Since they were forced to move out of their forest homelands in 1952, however, they have had to sneak into the park illegally to gather the marijuana plants.

The people in Mubawa’s village work as day laborers in the surrounding fields, or they sell bundles of firewood gathered illegally in the park. Many have resorted to growing marijuana right in the village. Mubawa showed the writer a handful of marijuana plants in a garden plot, worth the equivalent of 50 cents. The plants could earn a family the equivalent of U.S.$8 to $100 per week.

The Mbuti will save and use for medicinal purposes the marijuana that they don’t sell. A traditional healer will grind the seeds and mix them with water to cure stomach aches. They will knead the seeds into a starch that they believe improves the appetite. They will make a tea from the leaves to help treat fevers, flues, coughs, parasites, and fainting. Mubawa told the National Geographic, “Like in America you take coffee—it makes you strong.”

But there is a significant cost to their growing, selling, and using the illegal plants. Soldiers from the Congolese army frequently patrol the village. During the author’s two-hour visit, three or four of them kept patrolling the community. But it wasn’t clear whether they were there to buy marijuana or to enforce the law. The villagers told her that if the soldiers have just been paid, they’ll be there to buy; if not, they will confiscate the plants and demand “fines.” Mubawa told her, “If you have money, you pay, if not, they beat you until they get tired. He has a gun; I have an arrow.”

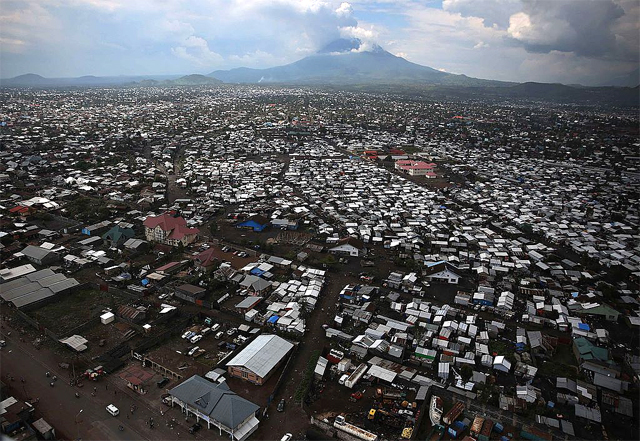

The author visited places in the city of Goma where the marijuana is sold and used. One sub-lieutenant in the army said that using and selling marijuana in Goma is certainly a better way to supplement his salary than looting or stealing. He does it so his family can survive. Besides, the sale of the drugs allows him to send his six kids to schools, where the fees for uniforms and books would otherwise make their attendance impossible. He has been arrested for selling the drugs, but he simply pays a $50 bribe to avoid spending any time in jail and gets back to his normal life. “My children have grown up because of marijuana,” he said.

The Mbuti appear to have a similar attitude of the need to be practical with existing realities. The international aid organizations that are active in the region are involved with all the problems of North Kivu province except those of the indigenous people, they feel. At a shantytown for the Mbuti outside the city, at a place called Bulengo, one Mbuti father sat outside and told the reporter that he does not have a job. He said he is only able to feed his 10 children because he is growing marijuana right next to his hut; because of it, he is able to provide at least some food for his family.

However, people who agree to stop growing marijuana—only six out of the 65 families in the camp do agree—are the only ones who are registered as internally displaced people and are therefore permitted to receive assistance. The other families, who refuse to agree, are only allowed access to water and to the health clinic. They get no food supplements. However, the leader of the shantytown reasons, “this clinic won’t stay here forever [but] we will always have marijuana.”