A Muslim man and his Christian bride, both Nubians, were married at night recently to avoid upsetting too many people, but they had a traditional ceremony nonetheless. Nicola Kelly described the events that took place in the Aswan area for the BBC last week.

Akram, the groom, told the reporter on the morning of the wedding the circumstances of the romance. He was advised by many Muslim Nubians to marry within their community, “but it was impossible. I couldn’t stay away from her,” he said, referring to his betrothed, Sally, the Christian girl. But it would not be a traditional wedding ceremony: he would go to the mosque and say his vows alone, while she would stay at home and recite her prayers.

Although Muslim and Christian Nubians have mostly gotten along, this romance has been quite unusual and difficult. The man and woman are both from Shadeed, a village that is part of the Aswan metropolitan area located on the west bank of the Nile. They met seven years ago across the river in the city of Aswan. They were hanging out in a spot where young people eat ice cream. They flirted; she enjoyed his jokes; he looked forward to seeing her. But as things became serious, both families tried to keep them from seeing one another. For seven years they only met sporadically. Although marrying someone from the other community is not absolutely forbidden, it is highly frowned upon.

During the week before the marriage, Akram has gone from door to door in his community issuing oral invitations to his evening wedding. It’s a Nubian tradition, Kelly writes, since people would feel insulted if they only received written invitations. “Speaking to our neighbours, singing songs, eating and dancing. That’s more important to us grooms than the religious part of the day, anyway!” he told the BBC.

Heading into the mosque, he pointed out to the reporter the ruins of some Christian buildings that were destroyed by outsiders. Christian facilities have been attacked by the majority Muslims in Egypt in recent years, but the Nubians apparently wouldn’t allow any more. They drove the outsiders away, he told the Ms. Kelly.

The reporter found the imam to be a humble, scholarly man; he told her that marrying someone of the other faith was no big deal. “I want people to accept each other. Muslims and Christians, we can live in peace,” he said. He went on to say that Christianity in the Nubian community has had a very positive effect on the young Muslim men.

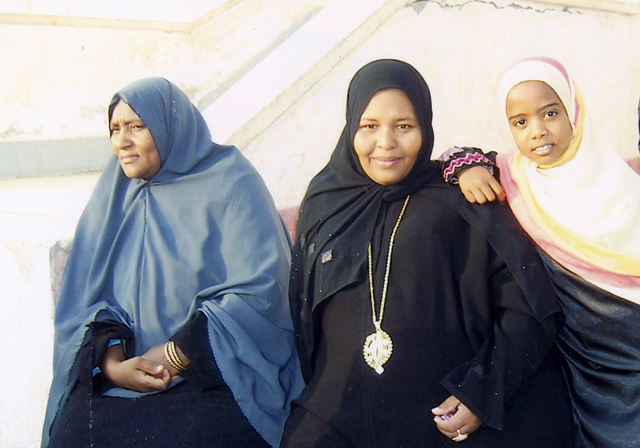

Sally spent most of the day in her home on the other side of Shadeed preparing herself for the wedding. There was a cross above each doorway in the house and she had a rosary necklace around her neck. She needed the time to settle her nerves and get the traditional henna painted on her hands and arms so she would be beautiful. As evening approached, she and the other women took a ferry across the river to a hairdresser, emerging a couple hours later looking much different than she did as an 18-year old girl that same afternoon. “I feel very confident. I am very beautiful now,” she told the reporter with a lot of self-assurance. The photos that accompany the BBC story confirm her opinion.

She told Ms. Kelly that it had taken years of quiet discussions with her husband to be—and many not-so-quiet conversations with her father. He had sternly forbade the marriage until both the imam of Akram’s mosque and their own pastor had agreed, and he finally relented.

At the salon where the ceremony would take place, Akram arrived, hours late, shortly before midnight. Goatskin drums were distributed among the guests as he entered the salon—and then ululations and applause when the happy couple emerged with their arms linked. But the important part of the event was the dance. At first, the women danced separately from the men. They danced in a circle around the bride.

Then, Akram’s relatives and friends raised him up onto their shoulders and they threw him into the air in time with the beating of the drums. He hollered that that was the best part of the evening so far. Next, the crowd parted to allow the bride and groom to face each other and dance around one another, though still not touching. After five minutes of that, the drumming stopped and the husband and wife stood beaming at each other.

Akram exclaimed that now they could go home, eat, and begin living together. The reporter asked Sally if she was looking forward to the next phase of her married life. She replied that she was certainly eager to have lots of children, and added, “I hope now everyone will accept our marriage and it will become easier for us.”

In her book Nubian Women of West Aswan, Jennings (2009) provided a recent ethnographic analysis of the situation that women in communities such as Shadeed face when they contemplate marriage. A lot of her descriptions of the typical Nubian courtship customs clearly didn’t apply to the interfaith romance between Akram and Sally—the BBC account supplements her engaging stories and scholarship—but the anthropologist provided useful background information. She wrote, for instance, that “Nubians tend to be intensely romantic, and young men in love press their suit with poetry, songs, and beautifully worded compliments (p.59).”

In her book Nubian Women of West Aswan, Jennings (2009) provided a recent ethnographic analysis of the situation that women in communities such as Shadeed face when they contemplate marriage. A lot of her descriptions of the typical Nubian courtship customs clearly didn’t apply to the interfaith romance between Akram and Sally—the BBC account supplements her engaging stories and scholarship—but the anthropologist provided useful background information. She wrote, for instance, that “Nubians tend to be intensely romantic, and young men in love press their suit with poetry, songs, and beautifully worded compliments (p.59).”

She wrote, however, that it is the Nubian woman who establishes the nature of the courtship rather than the man. In that vein, it is clear from the BBC article that it was Sally who had to win over her father, with the help of the imam and the pastor, not Akram. But Jennings emphasized that the family, especially the father, usually has the final say about the man that his daughter will be allowed to marry.

But the anthropologist discovered many shades of permissiveness in the West Aswan Nubian fathers. Some were skeptical of their daughters’ abilities to choose a man who would be a stable, reliable provider over the long term. Older heads are wiser. Other parents that Jennings spoke with told her that they felt that romantic love was a really essential component of successful marriages. People she interviewed pointed to examples of successful marriages in the village that had been based on love matches—but others pointed to unsuccessful matches to support their opinions.

If Jennings returns to the West Aswan area to work on a third edition of her book, one can hope she will be able to locate Akram and Sally in order to find out how their marriage has been working out.