The Yanadi in Andhra Pradesh are asking why their customs do not seem to have any standing with local officials. They are upset that a marriage between a 17-year old Yanadi boy and a 13-year old girl was broken up by officers who decided that the girl was too young to be married. The Yanadi claim that child marriages are part of their customs. The Hindu broke the news about the intervention by officials in their family affairs in late May, but an account on June 18 in The Indian Express provided better details about the clash.

The parents of the young people had worked as guards at a mango orchard so they had grown up as playmates eating mangoes under the trees. At some point the two became inseparable, fell in love, and decided to marry. The parents of the girl proposed marriage to the boy and he agreed. In their community, marriages as young as 14 or 15 are still common, according to The Indian Express.

The couple lived with their families in the Yanadi hamlet of Eguva Bandarlapalle, in the Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh. A government official with Integrated Child Development Services heard about the love match while doing work in the tribal hamlets that surround the Koundinya Wildlife Sanctuary. With police support, she went to the hamlet and told the Yanadi that the impending marriage violated national law, the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act. Citing the law, the officials seized the girl and sent her to a hostel run by a group called the Rural Organization for Poverty Eradication.

The Yanadi strongly opposed the intervention by the officials. It was their tradition for girls to marry when they reached puberty, they said, and if a couple had decided to marry, age was not an issue with them. They added that marriages depended on work being available, and a boy who had a job was free to marry a girl, even if she was under 18.

The official who had intervened spoke defensively to The Indian Express. Ms. M. Nirmala, the Child Development Project Officer, said that the wedding ceremony had not taken place yet when she heard about it and intervened. She continued, “Irrespective of their customs and traditions, it amounts to child marriage.” She did not accept that the young people are in love. The girl had dropped out of school while she was a member of class 5, and it was the families that had decided to marry them, she asserted. Ms. Nirmala is attempting to convince the parents to prevent the girl from getting married until she turns 18.

If the parents do not agree to prevent the marriage, the girl will be required to remain at the hostel where she will receive training for tailoring. If they do, the agent has made arrangements for her to be admitted to a Kasturba Gandhi Balikala Vidyalaya school in Andhra Pradesh. The KGBV schools are residential facilities set up by the government of India to provide schooling for girls from disadvantaged groups such as scheduled tribes like the Yanadi who would not otherwise get an education.

The families of both the girl and the boy objected to the intervention by the officials and the police. Chibasa Seetaiah, the father of the boy, spoke forcefully to the reporter: “When the girl’s parents do not have any objection, why are these women [the officials] objecting? Government rules do not apply to us because we follow tribal customs. My son has not said anything to me but the girl’s father said they already got married in the forest, so why are they now being separated?’’

The father of the girl, Rajababu, told the police that he was not opposed to the marriage, which he said had already occurred, because the boy was also a Yanadi. Furthermore, he was employed as a worker at a dhaba, a roadside restaurant.

S. Kamarunissa, an official for the Palamner Police Division, told The Indian Express that the families had shown the officials the mangalasutra, the necklace that had been used during the wedding ceremony of the young couple. A mangalasutra, literally a sacred thread that a groom ties around the neck of his bride to signify that they are married, is widely used in India.

Despite the evidence of the sacred thread that the families produced, the officials were unrelenting. “However, since it is a child marriage, we seized it and told them the marriage was illegal,” the official said. Although they resisted initially, it appears from the conclusion of The Indian Express news story that the Yanadi are not going to contest the issue any farther. The boy, fearing the police, changed his story and lied to officials, saying that he and the girl had not gotten secretly married in the forest. (The earlier news report in The Hindu gave more details about their forest wedding.) But the Yanadi have a long tradition of accepting the dictates of authority figures: the parents of the girl relented and said they would agree to allow her to remain in the hostel.

The literature on the Yanadi provides a lot of information about their marriage customs, including their tradition of allowing child brides. The scholarship supports their position in this controversy. Rao (2002) wrote that a Yanadi girl could be married traditionally around age 13, as soon as she reached puberty, while a boy was considered ready for marriage when he started growing a mustache, or about age 15. At Rao’s study site—Sriharikota Island in the late 1970s—out of the 234 married couples he surveyed, the men were two to five years older than their wives in 229 of them.

“Marriage is seen as a natural phenomenon and it is considered unnatural to be a bachelor or a spinster,” Rao wrote (p.142). He added a most interesting observation: Yanadi believed that if men didn’t get married, they would fight for females and, similarly, if women didn’t marry, they would fight for males. Hence, without marriages, disorder, chaos and violence would reign.

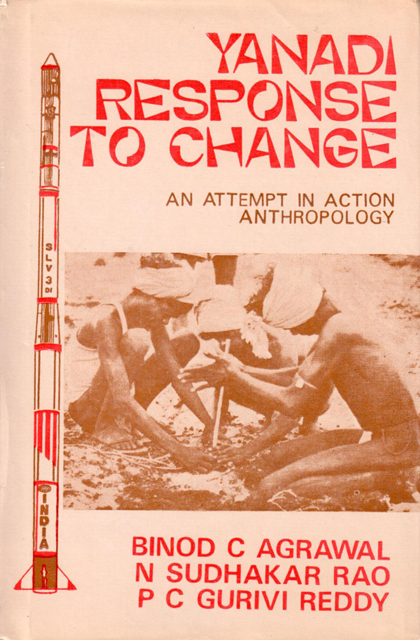

According to the book Yanadi Response to Change, an Attempt in Action Anthropology by Agrawal, Rao and Reddy (1985), in traditional Yanadi society the consent of the girl was essential when marriage negotiations were taking place between families. Perhaps the earliest account of the Yanadi, made by one John Shortt in 1864, confirmed Agrawal, Rao and Reddy. According to Raghaviah (1962), Shortt wrote that a Yanadi marriage was based only on the consent of the couple. The young man and woman would arrange their wedding themselves. He would tie the marriage string on the neck of his bride and they would then go to the husband’s home. Yanadi women were never married before they had reached puberty.

According to the book Yanadi Response to Change, an Attempt in Action Anthropology by Agrawal, Rao and Reddy (1985), in traditional Yanadi society the consent of the girl was essential when marriage negotiations were taking place between families. Perhaps the earliest account of the Yanadi, made by one John Shortt in 1864, confirmed Agrawal, Rao and Reddy. According to Raghaviah (1962), Shortt wrote that a Yanadi marriage was based only on the consent of the couple. The young man and woman would arrange their wedding themselves. He would tie the marriage string on the neck of his bride and they would then go to the husband’s home. Yanadi women were never married before they had reached puberty.

But things are changing. A recent study of the Yanadi by Stanley Jaya Kumar (1995) noted that while marriage is a universal practice among them, in his study community Yanadi women married when they were between ages 15 and 20 and men when they were between 18 and 25.

Perhaps if the child welfare and police officials in the Chittoor District had been aware of their traditions and history, they might have been more sympathetic to the Yanadi perspective. They should have realized how strongly the Yanadi feel about marriage, yet how they are recently adapting to the demands of the nation by marrying when they are older. And the questions the Yanadi are asking remain challenging: how much should the spirit of their ancient traditions be followed when they conflict with the laws of the nation?