Canada’s CBC Radio rebroadcast a documentary on January 4 about Elisapee Ishulutaq, a renowned Inuit artist who died on December 9, 2018. The program had first been aired in June 2014 when she was in her late 80s and was appointed to the Order of Canada.

As a child in the 1930s, Ishulutaq lived with her parents out on the land in Baffin Island. But when she was in her 40s, she moved into Pangnirtung, a community on the island that has become famous for its art scene, where artists do a worldwide business in the sale of traditional subjects depicted in sculptures, weavings, and prints. Ishulutaq, who loved to draw, helped establish printmaking as a prominent art form in Pangnirtung. According to the CBC, “her art has helped define how the Inuit are seen around the world.”

When David Gutnick from the CBC met with her, she was in her late 80s and mostly confined to a wheelchair which her grandson, Andrew Ishulutaq, pushed her around in. He also interpreted for her since she only spoke Inuktitut. The day they met, however, she was kneeling on the floor holding a paintbrush in her hand.

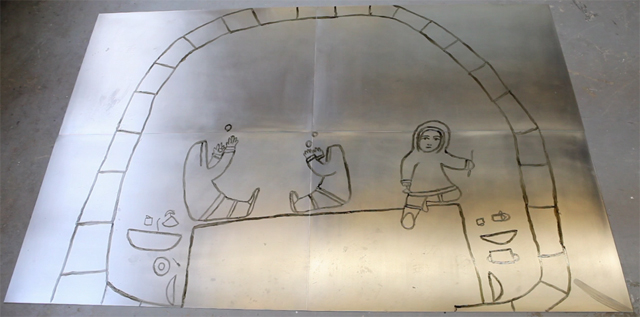

She was singing a song from her childhood, a song about the long, dark winters in an igloo in the North. She sang about children tossing a caribou skin ball for hours to one another, the only light coming from a seal oil lamp. And she spent that recent morning transferring her memories of those times into painted images that would outlast her. She spent over an hour on the floor and painted, as a result, an outline of the walls of an igloo and a girl with a very serious face, a caribou ball suspended above her.

Decades ago, when Canadian authorities decided that the Inuit would no longer be allowed to roam around on the land and had to stay confined to villages, it posed extraordinary hardships on them. Ishulutaq remembered that her father struggled to find enough seal at night to feed his family. They became so desperate that they were forced to eat seal skins. Their dogs were shot to prevent them from continuing to live nomadically. Ms. Ishulutaq had powerful memories to cope with.

Sylvia Safdie, a filmmaker, was also present during the CBC visit that day. She remarked on the deep-set emotions she could perceive in Ishulutaq’s face. The elderly lady has lived through so much, she observed. “It is the way her eyes move, they light up and then they become sad,” she said. She added that the artist does not function in theory. Instead, Safdie said, Ishulutaq functions “from within, and that is the essence of art.”

Ishulutaq suddenly remembered something else and stopped painting. Her memory was of her grandfather and how he used to play the Inuit violin, which nobody plays now. “So many people would be up on their feet, dancing,” she recalled.