The Guardian sent reporter Hannah Ellis-Petersen to Kuala Koh to investigate the tragedy that nearly destroyed the Batek village. Was it just an outbreak of measles that took down so many people starting about four months ago? Are the government analyses that it was just an outbreak of measles accurate or are officials covering up deeper environmental problems that are proving deadly to the defenseless forest dwellers? The journalist teases out the questions even if she doesn’t always provide pleasant answers.

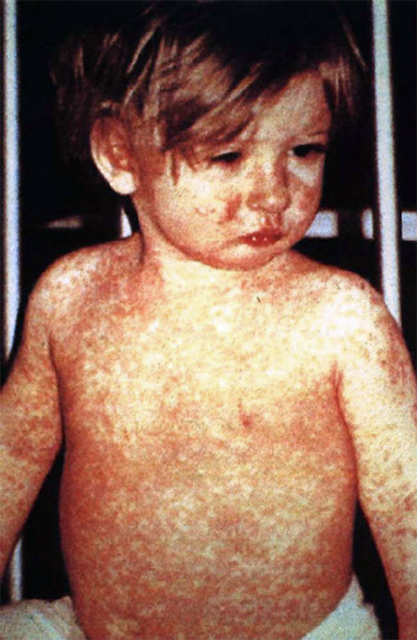

Regular readers of these news stories may recall reports on April 4 and April 18 that described a mysterious illness that was infecting the villagers. Another on June 20 described how the disease had become a deadly epidemic, killing and hospitalizing much of the village. Malaysia became alarmed, various experts were quoted, and the possible causes—rampant nearby mining, logging, water pollution—were debated. The government health authorities fixed the blame on a measles epidemic.

A news story on July 11 sought to wrap up the tragedy with discussions of the measures that the Malaysian government authorities were taking to protect the health of the Batek people. Alberto Gomes was quoted as describing the numerous underlying conditions endured by the Batek that may have contributed to the intensity of the disease.

The latest wrap-up report by The Guardian on September 7 makes it very clear that the Batek themselves still believe they suffer due to a wide range of discriminatory hazards that they must endure. The report by Ms. Ellis-Petersen is well worth careful study.

The final statistics are sobering: only about 20 people out of the 186 Batek living in Kuala Koh, a community at the edge of the Taman Negara National Park, were untouched by the illness. Over 100 were sent to a hospital and 15 died. Sita Keladi, a village resident, told the paper, “It was very scary for us….We did not know what was happening but people were dying around us.”

The government pledged to do a full investigation which would include autopsies of the bodies exhumed from their traditional forest burial sites but, after four months, nothing has been released. Why not, the Guardian journalist inquires, echoing the questions being posed by Orang Asli experts and the Batek themselves.

One question being asked is the relationship of the tragedy to the heartless deforestation going on around them, both for the development of palm oil plantations and for a nearby manganese mine. Johan Tahun, a 60-year-old man, complained to the reporter that their forests have been cut down, their homes destroyed, and their environment poisoned.

Ms. Ellis-Petersen writes that the Batek, much like the other Orang Asli (Original People) groups, are not respected for their indigenous knowledge and way of life. Instead, they have been relocated and integrated, supposedly, into the broader Malaysian mainstream. This makes it easier for the corporations to cut down their forests and for the government agencies to take away their resources. Palm oil plantations make more money for the people who matter.

Kuala Koh was founded in 2010 by the government, which gave them a tract of land and a half-dozen concrete house that the journalist visits. She describes them as dark and dirty with bars on the windows. They look to her like prison cells. The kids can’t go to school—the nearest one is more than 60 miles away—and with their traditional forests destroyed, the Batek are mostly illiterate and do not have much of a future.

Johan Halid from the organization Sahabat Jariah told The Guardian that the government simply doesn’t care what happens to the Batek. “Without the jungle, they have nothing, and without access to power and schools there is also no way for them to integrate into society,” he said. He alleged that when the people of Kuala Koh began dying from their illness this spring, he tried alerting the authorities and got nowhere. It was only when one of his posts on a social media website went viral that the department of health got involved and used a van to take some sick people to a hospital.

More help was needed—others urgently needed care—but the government delayed because of a national holiday. In the five days that elapsed until another rescue van was dispatched to the village, two more people had died, including a young child. Rosli Long, whose three-year old son had died in the hospital, expressed resignation to the reporter: that’s “just how things are for us.”

The Batek, as well as Orang Asli advocates, dismiss the statements that measles was the sole cause of the tragedy. They continue to blame environmental pollution, deforestation, malnutrition, and neglect as major factors in making the villagers so susceptible to the disease. They claim that the villagers are affected by the extensive quantities of pesticides used in the palm oil plantations and they are further affected by the explosives and detritus produced by the nearby manganese mine.

The journalist contacted the president of the Federation of Private Medical Practitioners’ Associations Malaysia (FPMPAM), Dr. Steven Chow, for his reactions. He says that since the Batek immune systems are already compromised from their persistent malnutrition, the harmful health effects of the manganese pollution would be magnified ten times. A visitor to the Batek communities on many occasions, he says that outside environmental factors such as pollution from the mine were at least partially responsible for the deaths. He too remarked that the promised government report about the tragedy has not yet been issued.

An FPMPAM report to the ministry of health described the Batek habitat as “a death trap,” an observation that did not surprise any of the villagers. Their only supply of drinking water comes from a small pond whose waters used to run clear. But since the manganese mine has begun operations, the drinking water now becomes cloudy from the waste generated by the nearby mining.

Mohammad Potok, a 42-year-old villager, tells the reporter how they watch their drinking water change colors due to the toxic mine waste whenever it rains. “But nobody cares if we are drinking poisoned water,” he says. He adds that the Batek think that the polluted water was one of the causes of the epidemic.

Dr. Chow dismisses the claims that measles was the sole cause. He expresses cynicism about the likelihood of the government ever accepting any responsibility for the tragedy. Accountability should go to the top of the government but he doubts it will do anything but seek to bury the matter. “In 20 years I would not be surprised if there is barely any of the tribe left,” he concludes.