A nonprofit business flourishing in a village of Mexico’s Oaxaca state is inspired by traditional Zapotec values and the ideals of Mohandas Gandhi. A story in Yes! magazine last week describes the revival of the traditional spinning culture of the village, its adoption of effective business practices, and the influence of the Mahatma.

The story begins in San Sebastian Rio Hondo, a poor Zapotec town in the rugged, forested hills of the Miahuatlán District, in the Sierra Sur Region of Oaxaca State, about 75 miles south of Oaxaca City. Around 50 years ago the economy of the town changed in part from spinning and weaving in homes to the purchase of cheap, industrial clothing.

Eliseo “Cheo” Ramírez, born in the town 32 years ago, tried at age 16 to flee the growing poverty by heading north toward the U.S. But he nearly died while crossing the desert, so he gave up that prospect and focused his energies on co-founding a nonprofit textile business called Khadi Oaxaca. His vision, shared with his co-founder, was to regenerate a sustainable way of life for his community based on their traditional economic activity.

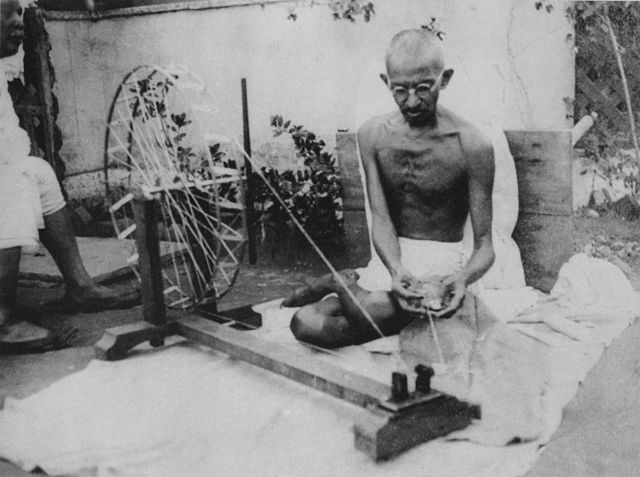

The co-founders of the new business were Mark “Marcos” Brown, the son of an American businessman, and his wife Kalindi Attar. A much older man than Ramirez, Brown had spent time in 1974 as a teenager in San Sebastian and had developed a life-long fondness for the town. He later traveled to India and had the privilege of living for two years in Gandhi’s ashram. There he learned about satyagraha and the importance to the Mahatma of handspun cloth called khadi, which had become symbolic of India’s independence. Khadi signified local pride and resistance to the outside, British industrial, control of the economy.

Brown vowed to live according to Gandhian values and to see how, based on them, he could help his friends in San Sabastian. In 2010 he moved to the town with a charkha, a Gandhian spinning wheel, and a plan to get the women of the community involved with spinning once again. The village carpenter replicated the charkha and Brown gave it to Ramirez and his wife Felipa, teaching them how to spin with it.

With Ramirez and his wife in charge of spreading the spinning, the partners soon had 20 women, most of whom were grandmothers, involved. Their hand labor, combined with the skills of other artisans, began producing a range of textiles that the businessmen were selling widely in Mexico and the United States. The profits went back to the spinners, weavers, and others who had produced the cloth.

Until this spring, Attar and Ramírez attended fashion shows representing their company and found that people would often ignore other exhibitors but stop at their small booth. They were attracted by the hand-crafted textiles on display.

Brown, in his comments to the journalist, Tracy L. Barnett, quoted Gandhi’s outlook on small communities like San Sebastian and their ways: Brown said, “(Gandhi) would always say, when we talk about village economics, if it comes from a place of nonviolence, of a truly sacred economics, then you don’t need any commercialism; you don’t need to market that which has its essence and its beginning in goodness.”

The nonprofit business has grown rapidly over the past ten years. The managers have raised the pay scale for the thread spinners nearly four-fold, from 400 to 1500 pesos per kilo of thread the spinner produces. The thread production employs 350 spinners, a cottage industry that has revived the prospects for prosperity in the community.

The pandemic, however, has shut down the expos, which drew tourists to the Khadi Oaxaca textile products. This development is hurting the sales in a variety of ways that Ms. Barnett explains. In response, the company has developed an online presence and it has not had to cut back on the extent of the spinning. Despite the lockdown policies in effect in Mexico, Khadi Oaxaca has been able to expand its number of active spinners by adding 100 more.

Gandhi would be proud of them.