July 2nd marked the 50th anniversary of a grim event: the first atomic test by the government of France on the island of Mururoa in French Polynesia. Radio New Zealand last week remembered the 30-year series of nuclear tests, from 1966 to 1996, by reviewing their effects on the Tahitian people and the protests that have been roiling the South Pacific over the past half century.

France, seeking to build its own nuclear arsenal, first started testing weapons in Algeria in 1960. However, the independence of that country in 1962 prompted the French government to seek another location to do the testing necessary for perfecting atomic bombs. It selected Mururoa and Fangataufa, two remote atolls in the Tuamotu group of French Polynesia, 750 miles east southeast of Tahiti for the testing.

Mr. Winiki Sage, the head of the Economic, Social and Cultural Committee of French Polynesia, told the reporters that there were some protests in the assembly of French Polynesia when the government announced that the tests would be taking place. The protests were overruled. The government’s assurances that the testing would be safe were accepted by many people who also believed arguments that the build-up of military forces needed to conduct the testing would bring economic benefits to the territory.

Mr. Sage said that President de Gaulle went to the territory to reassure the Tahitians, and more broadly all the Polynesian people; everyone accepted what he told them. “I can tell you that in the house of my grandmother there was a nice picture of a big nuclear bomb test,” he said, “and everybody was thinking it was something nice. We didn’t really know that it was something bad for us.”

That nuclear explosion 50 years ago on Mururoa was the first of 193 tests set off in French Polynesia over the following 30 years, until the government finally stopped the testing in 1996. Some of the devices tested were 200 times more powerful than the bombs dropped by the U.S. on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

The fallout from the bombs affected the health of the Tahitians off to the northwest, and the condescension of the French government in the matter has persisted to this day. According to Mr. Sage, the testing program was cloaked in complete secrecy by the French government. The potential harm that could be caused by the radiation was not revealed to the thousands of people who worked near the test sites—they were only protected by their t-shirts and shorts. Some were employed as close as 15 km from the test site. The Polynesian employees near the test site were not warned of the dangers of eating fish that they caught.

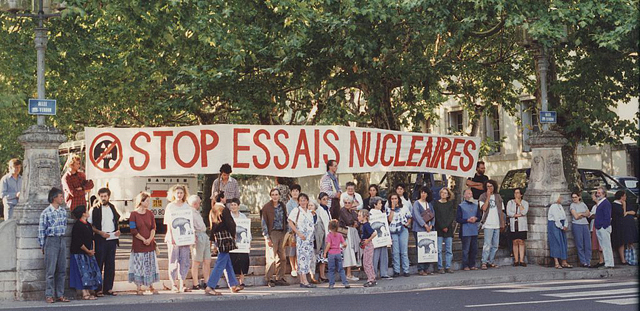

The testing soon became controversial, however. The USSR, the United States, and the United Kingdom had concluded their nuclear testing in 1963, but the French continued. By 1973, protests by environmental groups were becoming common, both in Polynesia, France, and elsewhere.

The government placed a moratorium on testing but President Jacques Chirac authorized a resumption of testing for the warheads of submarine missiles in 1995. This prompted strong protests from other Pacific countries and intense anger among the Tahitians. Riots broke out in Papeete, the capital of French Polynesia, causing damage amounting to millions of dollars. The rioters burned down the terminal at the airport. President Chirac ended the testing the following year.

The government of France insisted throughout this period that the testing program posed no threats to human health or to the environment. However, Richard Tuheiava, a senator in the territorial assembly, strongly disagreed. An outspoken advocate of the Tahitian language, Tuheiava argued that the effects of the testing are quite clear.

He pointed out that since the nuclear testing, the rates of cancers and leukemia have risen considerably according to scientific studies. Despite the evidence, the government of France, until 2009, denied that the testing program harmed the health of the Tahitians. Then, it introduced a program to grant payments to victims of radiation. Out of over 1,000 people who have submitted claims, however, only 19 have been awarded any compensation.

French President François Hollande visited Tahiti in February this year and urged the Tahitians to “turn the page” on the testing issue. He made promises for more compensation; he authorized funding for the oncology department at the hospital in Tahiti. Perhaps of greatest significance, he admitted “that the nuclear tests that took place between 1966 and 1996 in French Polynesia had an impact on the environment, and caused a plethora of health issues among its populace.”

But the Tahitians are becoming tired of promises from the government. Ten years ago, the news media carried reports about the health effects of the testing program during the 30 years it was carried out. People today are reacting with more than just cynicism. On the 50th anniversary less than two weeks ago, Tahitians held marches and ceremonies to protest the residue of the atomic testing program that they still have to live with—and suffer from. Mr. Sage said that the people of Papeete opened an exhibition to retell the story of the atomic testing and its lasting effects on their heath.

Senator Tuheiava told Radio New Zealand that he doubted that President Hollande will ever carry through on his promises to the 280,000 people of French Polynesia. Mr. Tuheiava has recently taken the issue to the United Nations. He said that he is going to make it very hard for France to continue to avoid taking responsibility for what it has done to so many Tahitians over the past half century.