A young Lepcha woman who has professional university degrees and works as a librarian in Gangtok, northern India, is pioneering the revival of traditional women’s clothing. Tshering Lhamu Lepcha, who goes by the alias Tshela, experiments with fashion designing, particularly clothing that revives the styles worn traditionally by Lepcha women. The regional Indian publication The Northeast Today published a profile of Ms. Lepcha last week.

In November 2012, Ms. Lepcha presented her first designs of modified traditional clothing at an exhibit called the Himalayan Ethnic Lepcha Fashion Event (HELFE) in Gangtok. The 29-year old emphasized to the interviewer that “Lepcha costumes need not be just regularly traditional with monotonous designs and fabrics but [they] can also be interpreted with modern or contemporary aesthetics yet with the traditional essence and ethos.” Her designs, she said, made a favorable impression on viewers plus the 20 or so other designers present.

The reactions she received at the HELFE event prompted her to persist in her creativity and she exhibited at another fashion show in the city of Kolkata in 2013. She hired a tailor and opened a tiny shop that year, and launched her business on a Facebook page, which prompted more orders. Soon she was getting orders for festivals, school events, weddings, and for formal office wear.

Ms. Lepcha has no formal training in fashion design—she has a master’s degree in library science—but that doesn’t lessen her passion for her art, her urge to experiment, and her determination to build a business. The growth of her business forced her to move out of her first space into a larger boutique called “Tshella’s Traditional One Stop” in Gangtok, the capital of the state of Sikkim. She has a support staff of two tailors, two craftsmen who do embroidery work, and a manager. She continues her librarian profession and does her fashion work in her spare time.

She makes it clear that her mission is to foster “professionally designed Himalayan ethnic attires.” Tshela’s Traditional One Stop is designed to promote pride in ethnic clothing—and to improve on it. She acknowledges that the Lepcha ethnic dress is perceived as having been quite limited in fabric choices and styles. She wants her creations to not only be worn on special occasions, but as regular, daily clothing. “This would also give the wearer a sense of pride and belonging to her/his heritage,” she said.

Ms. Lepcha spends a lot of time shopping for high quality fabrics, researching trends in the clothing markets, and searching for ideas for her growing business. She told the journalist interviewing her that she has no particular approach for gaining inspiration for her new designs. She gets ideas wherever she goes around Sikkim.

In addition to her regular profession as a librarian, she also spends some time as a social worker—her second master’s degree was in sociology. She regularly pursues a variety of social initiatives and participates in events organized by the Sikkim Lepcha Association. But to judge by the article last week, one of her foremost passions is her evening work managing and developing her fashion design business.

It remains a challenge for her. She tells the journalist that ethnic dress is rarely seen in Gangtok except at religious occasions, cultural events, or weddings. This is not a recent phenomenon, however. Halfdan Siiger, a Danish scholar who did ethnographic field work among the Lepcha over 50 years ago, wrote in 1967 that their fondness for their traditional clothing was fading at that time.

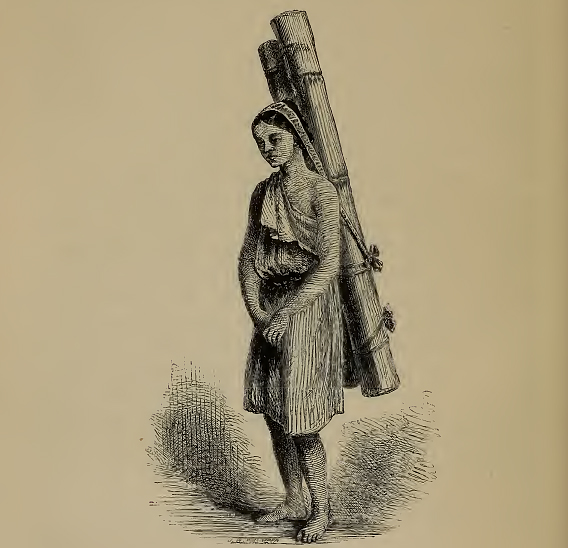

Siiger wrote (1967, p.71) that “owing to the increasing influence of the bazaars, where piece goods are sold and entire garments are made on sewing machines, the former types of clothes, as we know them from … about a century ago, are more and more falling into disuse, and nowadays few Lepcha women know how to make the clothes of the members of the family, as they used to do.”

On the other hand, a much more recent book on Lepcha culture by Sharma (2013) provides a somewhat different perspective on their clothing. She writes that the “traditional dress of the Lepchas is woven in exquisite colour combinations (2013, p.117).” Sharma goes on to briefly describe the ankle-length traditional flowing woman’s dress, called a dumvum, or dumdyam. It finally becomes clear why Tshering Lepcha called her first creation at that HELFE event in November 2012 “dhumdhem,” the traditional Lepcha female article of clothing.

Sharma says that today some younger Lepcha women have taken to wearing trousers and, less commonly, the shalwaar kameez, a generic term for various types and styles of popular Indian clothing. Sharma provides 91 color photos at the beginning of her book, some of which give good impressions of sometimes colorful—and sometimes drab—clothing worn by the Lepchas of Sikkim. Tshering Lepcha has an interesting tradition to enrich.