Deutsche Welle, the prominent German international broadcaster, carried a news story about the economy of the Ju/’hoansi on Saturday that provided a fairly hopeful perspective on the prospects for their Nyae Nyae Conservancy in northeastern Namibia. The reporters described, in an English language report, several different ways the people are now able to make money so they can buy supplies in a store in Tsumkwe, the major Ju/’hoansi community.

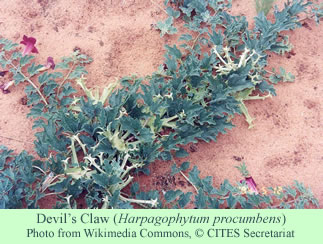

One of the more important economic enterprises in the conservancy is the careful, sustainable harvesting of devil’s claw roots (Harpagophytum procumbens) from the desert floor. These roots, a popular herbal medicine internationally, have to be harvested carefully and dried properly in order to keep the coveted organic certification. Records must be kept meticulously and procedures followed to the letter in order for the products to receive the international certificate of sustainable harvesting that consumers demand.

One of the more important economic enterprises in the conservancy is the careful, sustainable harvesting of devil’s claw roots (Harpagophytum procumbens) from the desert floor. These roots, a popular herbal medicine internationally, have to be harvested carefully and dried properly in order to keep the coveted organic certification. Records must be kept meticulously and procedures followed to the letter in order for the products to receive the international certificate of sustainable harvesting that consumers demand.

Klaus Fleissner from CRIAA, a South African consultancy, explained to the reporters how the inspectors do their work. After checking to make sure all the paperwork is done correctly, he told the authors, “we drive out to the villages where the people are harvesting the devil’s claw and look to see if they’ve filled in the holes again. This guarantees sustainability, and the most important point for organic certification is sustainable harvesting.” Mr. Fleissner admitted that the Ju/’hoansi have been harvesting the roots for centuries, so in fact they needed little instruction on how to protect the plants.

Since a modest number of tourists do visit the conservancy, the people, particularly the women, have learned how to make craft goods that will appeal to the tastes of the visitors. They cut ostrich egg shells into small pieces and string them into bracelets and necklaces. The Deutsche Welle reporters don’t mention that the Ju/’hoansi have been fabricating such things out of ostrich egg shells for a very long time. Making necklaces, bracelets and headbands out of shells used to be an essential part of their culture.

Anthropologists Megan Biesele and Nancy Howell (1981) described how their elders would instruct youngsters in the proper ways of making bead gifts, which they would then give away in order to form reciprocal, giving relationships. An article by Polly Wiessner (1982) described in even more detail the importance to their culture of teaching little children the value of gifting.

Grandmother would give an infant a gift made of beads. Then not long afterwards, she would take it away from the child, despite its protests, and show it how to make a new gift from the same beads to give to another person. The child quickly learned that the acts of giving, and the relationships that were built up, were more important than the actual objects themselves.

Wiessner (1984) subsequently described the headbands that the women made as gifts for one another, intricate works of art that were often the finest possessions of their owners. Doubtless such headbands would be far more work than necklaces and bracelets, and might not sell as well to most tourists from Germany.

Saturday’s news report also mentioned the stores in Tsumkwe—the small gift shop where the bead work is on display for the tourists and a general store for provisions. Frans Labuschagne, manager of the general store, sells mainly staples such as sugar, salt, and maize.

The nearby craft shop is run by a woman named Hoan. She evidently had to learn skills such as bookkeeping and marketing from a consultant named Martha Mulokoshi, who works for the Nyae Nyae Foundation. Hoan had to learn to take stock, write out receipts, and do all the little things that are important to running a business.

The Ju/’hoansi have other sources of income. One elderly man, Kunta Boo, frequently takes tourists on walks to demonstrate how he can live off the land. The tourists can, for five euros per night, stay at a small campsite near his village outside Tsumkwe, where people will perform their traditional dances.

The German International Development Service (DED) is advising the Ju/’hoansi on the advantages of turning their conservancy into a community forest. The authors of the article report that the conservancy will soon be awarded community forest status. Eckhard Auch from the DED argues that giving the community complete control over the resources on its land will be highly advantageous for them. The managers will then no longer necessarily have to get the approval of distant bureaucrats before making decisions that will affect the future of their resources.

Rachel Andima, from the forestry office in Tsumkwe, is similarly enthusiastic. Community forest status will encourage the people to conserve their own resources. “When they conserve them, they can use them for the future generations,” she said. Healthy, sustainable, community forests have been an important element in the culture of some Zapotec communities, as a news story a little over a year ago pointed out. It is good to learn that the model is spreading.