While national elections in India made headlines worldwide in recent weeks, a Kadar hamlet decided to boycott the polls in Kerala to make their own statement. An article in The Hindu explained their reasoning.

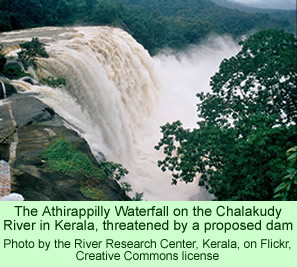

The various candidates for office in the state have not clarified their positions on the controversial 163 megawatt hydropower project on the Chalakudy River that threatens the famous Athirappilly Waterfalls as well as entire Kadar communities. The government calculates that 163 Kadar families would be displaced in the hamlet of Vazhachal and 71 in Pokalappara. Environmental concerns had stopped the dam project several years ago, but the state has revived the planning once again.

The various candidates for office in the state have not clarified their positions on the controversial 163 megawatt hydropower project on the Chalakudy River that threatens the famous Athirappilly Waterfalls as well as entire Kadar communities. The government calculates that 163 Kadar families would be displaced in the hamlet of Vazhachal and 71 in Pokalappara. Environmental concerns had stopped the dam project several years ago, but the state has revived the planning once again.

In order to avoid the polling process, the Kadar left town. Over 340 potential voters fled into the nearby forest to spend the day collecting so-called minor forest products—their traditional occupation anyway. Their boycott was an attempt to clarify what the state is planning to do to them, and to peacefully dramatize their situation.

At dawn on voting day, the people abandoned more than 70 houses in the two hamlets to go out and collect honey and gooseberries. While that sort of collecting is a normal, daily routine, the people hoped to avoid confronting government officials and political activists who might try pressuring them to go to the polls and vote.

M. Lakshmanan, a Kadar elder, told the paper that none of the candidates had been inclined to clarify what was happening regarding the Athirappilly project, which the Kerala State Electricity Board had recently revived. He unloaded his irritation on the reporter. “Politicians [have] always cheated us. We have no agricultural land here and our livelihood is at stake due to climate changes affecting fish wealth in the Chalakudy river and minor forest produce in the Athirappilly forests,” he said.

A mother of two children, J. Vineetha, said at the Pukalappara settlement that employment with the Forest Department does provide minimal earnings, but “we are also facing [a] dearth of health and educational facilities. Some prominent candidates even ignored visiting our hamlets,” she told the reporter.

Some time ago, the Kadar were promised land about 40 km away on which they could resettle, but they found out that the proposed area was too dry for farming—and it had no forests. It would be difficult for them to survive. They indicated that they would be willing to be part of the voting process if their genuine needs would be met. The settlements in the upper Chalakudy River basin represent their original, and only, homeland, The Hindu concludes.