A massive industrial wind project is under construction in southern Mexico near the city of Juchitán de Zaragosa, and the local indigenous farm families, mostly Zapotecs, are unhappy about it. Using the Zapotec name Biío Hioxo Energy, the developers are seizing lands in the name of alternative power development.

The project, reported recently from the state of Oaxaca, is one of numerous comparable industrial wind parks being built across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. The isthmus is well known for having average sustained wind speeds of between 20 and 30 meters per second (44 to 67 miles per hour) from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico.

The project, reported recently from the state of Oaxaca, is one of numerous comparable industrial wind parks being built across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. The isthmus is well known for having average sustained wind speeds of between 20 and 30 meters per second (44 to 67 miles per hour) from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico.

The farm of Don Celestino Bartolo is one of the ones affected by the construction. From the farmyard, his son Rosalino Bartolo points to the nearest wind tower, which is quite close to where he is speaking with a reporter. It is located where the family used to fish. Rosalino argues that people living closer than one kilometer away from wind towers may be subject to harm from magnetic fields, but “we see that there is one right here less than 150 meters away,” he says.

A recent article about the project, published by Truthout.org that was reprinted from a report posted on the website of the Americas Program of the Center for International Policy, cites, and disputes, numerous points made in an environmental impact study (EIS) of the project. The EIS was prepared by the URS Corporation Mexico for the developers. For instance, the study stated that waste oil has to be frequently removed from the turbines. It will have to be stored at the project site in Juchitán until it can be transferred to a hazardous waste facility.

The EIS argued that “the project will not generate an impact on indigenous peoples, their communities or their homes. Nor on their existing archaeological, paleontological, historical, religious and cultural resources within the project site.” Indigenous groups dispute those assertions.

Carlos Sanchez, from the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Juchitán, maintains that the wind developers ignore the communal property rights of the indigenous peoples. “Of the 15 parks already built on the Isthmus, 10 are on communal land, a total of 68 thousand hectares. In the Biío Hioxo Park alone there are seven sacred sites in 2000 hectares of communal lands,” he said.

The EIS also predicted hopefully that the project would not have an impact on the local groundwater. Sanchez expresses skepticism about that. He also said he was concerned that many of the indigenous farmers only know their native languages, and are not able to understand the Spanish used in the contracts that wind company representatives shove in front of them to sign. The farmers have been signing away their lands without understanding what they are doing.

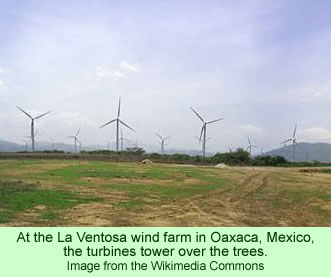

The recent article describes the harm that industrial construction poses for the natural environment, such as the fact that the massive towers kill birds and bats, they fragment the landscape, and they disrupt the foraging and sheltering needs of all wildlife. The article discusses the visual pollution produced by the towers jutting up into the relatively flat landscape. It also points to the high levels of noise that the spinning turbines produce.

The EIS reminds readers that industrial developments such as these require high voltage transmission towers, cables, and pylons—“visual pollution on the scale of big cities.” The environmental impact of the wind projects will be “significant, unavoidable and cumulative across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec,” it indicates. Over half of the projected 28 wind industry sites have already been built.

Earlier news stories have already reported on the controversies these projects generate within the Zapotec communities in the paths of the strong winds. Clearly, the problem is not going away.