In his book Non-Violent Resistance, Gandhi wrote that satyagraha is not a weapon of the weak, it is a tool of strength. He acknowledged the existence of passive resistance, particularly in the Christian tradition, but he dismissed it as a characteristic of weakness. Passive resistance does not completely exclude violence, he argued, if the passive resisters should turn in that direction. It is not clear if he was aware of the Paliyans and the other tribal peoples in India who express their nonviolence by passive resistance, often called nonresistance, by fleeing from confrontations.

If asked, the Paliyan would certainly not have agreed with Gandhi’s assessment. Anthropologist Peter M. Gardner (1972) quoted a Paliyan man who told him bluntly, “if struck on one side of the face, you turn the other side toward the attacker.” The Paliyan express their reluctance to engage in fighting by retreating from it—sometimes precipitously.

If asked, the Paliyan would certainly not have agreed with Gandhi’s assessment. Anthropologist Peter M. Gardner (1972) quoted a Paliyan man who told him bluntly, “if struck on one side of the face, you turn the other side toward the attacker.” The Paliyan express their reluctance to engage in fighting by retreating from it—sometimes precipitously.

Gardner amplified Paliyan attitudes toward peaceful nonresistance in a 2010 article, which appeared in a book on nonkilling societies. He suggested that Paliyan nonresistance must be seen from their perspective, rather than from the viewpoint of outside societies. Since the Paliyans still confront aggression in the same manner as the gentleman quoted in 1972, they do not see nonresistance in Gandhian terms, as a weakness.

Instead, they view their way of retreating from confrontation as a completely approved social style. They feel no stigma in avoiding conflicts, no humiliation in retreating from fights, no sense of cowardice. Gardner wrote that, for the Paliyan, retreating “is an unambiguous act of strength, strength in controlling oneself.”

Thus, there are two perspectives on peacefulness operating in India—the active, challenging style of nonviolent resistance perfected by the Mahatma, such as marches, sit-ins, and so forth—and the flee-into-the-forests nonresistance advocated by some of the peaceful societies. The differences may be subtle, but they are significant. Several news stories last week suggest that the continuing tradition of satyagraha in India, exemplified this time by a land rights organization, and the nonresistance of the Paliyans may be starting to converge.

On Wednesday, the Indian land rights group Ekta Parishad launched an epic protest by 50,000 landless Adivasi (tribal) people. They started a march from the city of Gwalior about 200 miles (320 km) north by road toward the national capital in Delhi. The protesters are planning to hand a memorandum to the central government describing the difficulties they face since they are still being deprived of their own lands. They hope to reach Delhi by October 29, marching by day and sleeping by night on the highway.

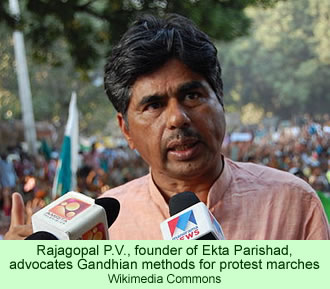

Ekta Parishad (Hindi for “unity forum”), a federation of about 11,000 community organizations, was founded in 1991 by the activist Rajagopal P. V. It focuses on land rights issues of the rural poor in India, particularly the tribal peoples. It follows nonviolent Gandhian strategies, particularly mass protest marches, in its attempts to negotiate with the national and state governments on behalf of the landless people.

Rajagopal led a similar march from Gwalior to Delhi in October 2007 with much the same demands. After several days of negotiations, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and his government agreed completely with the marchers and established a National Land Commission. The commission subsequently issued its report, but the government has not yet acted on it. The march this month is designed to press those demands.

A Paliyan contingent took a train to Gwalior early last week to join the march, and were singled out by a reporter from The Hindu, one of India’s leading newspapers. Priscilla Jebaraj, the reporter, spoke with Dhanalakshmi, a 22 year old Paliyan woman, who was listening at the back of the huge crowd along with others from her community. They were skeptical about a speech by Jairam Ramesh, the national Rural Development Minister. He was in Gwalior on Tuesday trying to head off the march with more promises.

“Discussion is always better than agitation,” he said to the vast throng. He listed the measures the government had already put in place to try and protect the rights of the landless. “Go home … we will find the middle path,” he promised. He had earlier agreed to sign clearly delineated policies that would protect the rights of landless rural people, but by Sunday last week the government had backed down and refused to sign. Ramesh said that land rights are issues controlled by the states, so the central government can’t make commitments.

Dhanalakshmi was not swayed by his reasoning, and told the reporter why. She said that in her state, Tamil Nadu, if she tells the government agent that she wants her rights to land, he says that there is no land for him to deliver. She rejects that, saying that the state government has plenty of land to donate to industries and to special economic zones. “He says, you get an order from above. So we are going to Delhi to get an order from above,” the spirited young woman said.

The young woman had never ridden on a train until she boarded the one for Gwalior a few days before. She crowded into an unreserved compartment with 200 other people to make the journey north. She was eager to tell the reporter her story.

She explained how, in 2010, a group of Paliyans were evicted from their traditional lands because of the Forest Conservation Act of 2006, and they had to work as bonded laborers on a mango plantation to survive. They were unable to obtain deeds to their lands, despite the provisions of the law, so 28 families occupied a plot of land and built small huts to live in at Serakkadu, in the foothills of the Bodi Agamalai.

The Forest Department threatened to demolish their houses, but Dhanalakshmi and the others refused to be intimidated. A news story in The Hindu in November 2010 about the 28 families and their hassles prompted the Chief Minister of the state to get involved and make promises that the tribal people would get the land and houses they were demanding.

Ms. Jebaraj, the reporter, noticed that the speakers at the front of the auditorium, Mr. Rajagopal and the government ministers, were mere specks in the distance for the people from Tami Nadu, and since they were speaking in Hindi, the crowd at the back couldn’t understand them anyway. But another Paliyan woman, Malliga, 35, said it really didn’t matter. She recognized that she didn’t have much in common with the people from the north of India. But she quoted a Tamil proverb to her purposes. “If one hand claps, it cannot be heard,” she said. “But if many hands clap, if we all join together, they will have to hear us.”

It sounds as if the precepts of satyagraha are penetrating into Paliyan society, so they may yet find ways to peacefully win their rights. Could Gandhi be persuaded that there is value in both active nonviolence and passive nonresistance—strength in both?