Mexico has doubled its wind power generation capacity during the past year but the Indian people, mostly Zapotec, who live in villages near the industrial projects are none too pleased. In fact, many of them are heatedly opposed to what they feel is the destruction of their environment.

People often think of wind power as being a benign source of alternative energy, but that is often not the case. Some environmental groups, such as one prominent organization in Central Pennsylvania, recognize the harm that the large industrial wind plants can cause to migrating birds, bat populations, and the integrity of the natural environment. Evidently, some of the Zapotec communities in Mexico that have to cope with the massive wind towers feel they are being marginalized, exploited, and their environments and resources severely impacted.

People often think of wind power as being a benign source of alternative energy, but that is often not the case. Some environmental groups, such as one prominent organization in Central Pennsylvania, recognize the harm that the large industrial wind plants can cause to migrating birds, bat populations, and the integrity of the natural environment. Evidently, some of the Zapotec communities in Mexico that have to cope with the massive wind towers feel they are being marginalized, exploited, and their environments and resources severely impacted.

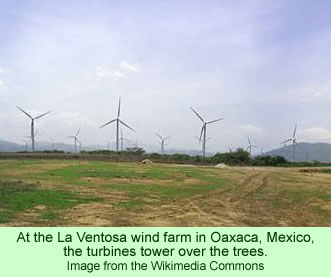

According to an Associated Press report last week, the huge wind farms—the towers and blades are hundreds of feet tall—are being built at a frantic pace along the Pacific Ocean coast of the Isthmus of Tehauntepec. Some of the developments are taking place near the Zapotec town of Ixtepec, about 115 miles east southeast of the city of Oaxaca, the center of Zapotec culture. The temptation to build the huge projects—hundreds of turbines are involved—is great since the Pacific coast in that region receives constant winds off the ocean to the south. There are now 14 completed wind farms on the Isthmus, four are under construction, and three more are scheduled for 2013. From 6 megawatts of installed wind capacity in 2006, when Felipe Calderon became the Mexican president, the country has grown to 519 megawatts today.

The politicians, bureaucrats, and corporate executives assure everyone that the developments will only be good for local residents. People are misled by suits who show up at meetings with small-scale models of the wind towers but don’t explain just how huge, noisy, and destructive the towers will really be.

At a meeting two weeks ago inaugurating the opening of yet another project, President Calderon extolled the rapid wind development. He said enthusiastically, “you can fight poverty and protect the environment at the same time.” He has pledged to cut Mexico’s carbon emissions by 30 percent by 2020, and he praised the added income the projects have provided.

The local people are not buying it. They are protesting, forming barricades, and risking beatings by thugs allegedly hired by corporate interests. Irma Ordonez, a Zapotec activist from Ixtepec, said it clearly: “We are asking these multinationals to please get out of these places. They want to steal our land, and not pay us what they should.” She added, “when they come in they promise and promise things, that they’re going to give us jobs, to our farmers and our towns, but they don’t give us anything.” She, along with other activists, traveled to Mexico City in October to protest.

In recent weeks, major confrontations have occurred at some villages belonging to Indian groups located near a spit of land that bounds a coastal lagoon about 30 miles southeast of Ixtepec. Many people there are fiercely opposed to the development of a 396 megawatt wind project offshore. A tense standoff occurred in late October when proponents of the project blocked a road against opponents who were planning to demonstrate.

Opponents believe that the project would damage a mangrove swamp, the breeding grounds of fish and shrimps which are the economic lifeblood of the coastal fishing communities. “Just when they were doing soil studies, there was a mass die-off of fish,” said Saul Celaya, a farmer who has become an activist. He added that opponents of the project “are being intimidated, they’re afraid to leave their houses, they’re threatened.” Industry sources deny that anyone has been threatened or intimidated.

Part of the problem is the way these projects are developed, which clashes with local Zapotec culture. Much Zapotec land is owned communally. “There is probably no worse place to make a land deal in Mexico,” said Ben Cokelet, the founder of a group called the Project on Organizing, Development, Education, and Research. Furthermore, local leaders are sometimes paid much higher prices than other people for their cooperation, which fosters tensions in the communities.

Promised benefits, such as lower electricity rates to the poor villages, have not materialized. The corporate officials bribe local authorities, sometimes with huge sums of money, to get them to sign away the lands that really belong collectively to the people. So far, those contracts have not been abrogated by higher government officials, most of whom follow the lead of the president and remain in favor of wind development.

In 2011, for example, a local official near the lagoon where the protests have been so active lately admitted he was paid between 14 and 20 million pesos ($U.S. 1 – 1.5 million) for granting, without consulting his village, the right to build a wind farm. When the outraged citizens demanded that he rescind the permission, he refused. Opponents fear that vibrations from the turbines along the coast will harm the aquatic life in the lagoon and, like the environmentalists in Pennsylvania, they realize that the spinning blades pose a serious danger to birds.

The resistance movement, in sum, is growing, despite intimidation and threats by the squads of hired goons who are trying to protect the industrial interests and their spree of construction projects. Leaders of the resistance movements are receiving death threats, and resisters who dare to demonstrate are threatened by gun-carrying thugs and, at times, by the police.

A news story earlier this year reported on the concerns in other Zapotec communities to the devastation caused by gold and silver mining. Two years ago, the news focused on the way some Zapotec comunities carefully manage their forests. The Zapotec people live in a resource-rich area of Mexico, but it is clear that many treasure their lands. They are unwilling to allow the for-profit interests to destroy their resources and their livelihoods.