Two very different news stories last week relate to the same theme: how should a country like the U.S. treat dissidents who violate its laws when they express their objections to warfare? One article was a reminder about the torture of Hutterites in military prisons in 1918, while the other is about Bradley Manning, a story that gained new depth with his testimony in a military courtroom last Thursday. The two issues raise interesting parallels—such as the use of torture by the army to enforce its way of thinking.

A news story posted last Thursday on a libertarian website from New Hampshire told the tale of two Hutterite men who were tortured to death in 1918. The reason for the torture was that they refused to serve in the army. The story is not pretty, and while it was told in these news pages as recently as March 2012, last week’s article provides some interesting new information.

A news story posted last Thursday on a libertarian website from New Hampshire told the tale of two Hutterite men who were tortured to death in 1918. The reason for the torture was that they refused to serve in the army. The story is not pretty, and while it was told in these news pages as recently as March 2012, last week’s article provides some interesting new information.

Four young Hutterite men were drafted into the U.S. Army in March of 1918 at a time when, in the fervor for active participation in World War I, there were no conscientious objector provisions in the American draft law. The four were ordered to report to Fort Lewis, in the state of Washington.

Other pacifist, Anabaptist groups at the time were willing to at least don military uniforms and to perform non-fighting, supportive work for the army. Not the Hutterites. They were too devoted to their fundamental beliefs, which absolutely forbade any fighting. They accepted, quite literally, the idea that Jesus had prohibited violence. Their faith was based, in large part, on turning the other cheek, as they felt Christ had ordered. Any cooperation with the military was completely wrong.

Because of their obstinacy, their refusal to cooperate in any way, they were sentenced to 20 years of hard labor at Alcatraz prison, in San Francisco Bay. There they were taunted, given minimal food and water, kept in solitary confinement, and subjected to continuous physical torture. For instance, they were kept in a dungeon and chained by their wrists high on a wall, so that their toes barely touched the floor. Medieval torture.

The signing of the armistice on November 11 that year ending World War I did not lessen their suffering. A week later, the Hutterite men were transported to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where two of them arrived nearly dead from their months of harsh treatment. Family members were notified of their condition, but one, Joseph Hofer, died before they could see him, and his brother, Michael Hofer, died a few days later. The other two men were forced to stand for nine hours per day in chains.

They were martyrs for their beliefs—an absolute dedication to avoiding violence. In response to the Hutterite story, Secretary of War Newton Baker issued an order prohibiting what was called “high-cuffing”—chaining prisoners high on walls.

The story of Bradley Manning and his release of state secrets to WikiLeaks in opposition to the Iraq war hardly needs to be summarized here. Manning’s lawyers have submitted a plea-bargaining arrangement for him and during his pre-trial hearing at Fort Meade, Maryland, last week, he took the stand to describe the abuses he suffered in military prisons. Like the Hutterite story, it, too, is not pretty.

By turning over vast archives of American military secrets to WikiLeaks, Manning clearly violated the laws—as did the Hutterite men in 1918. Some sources contend that the diplomatic cables he leaked may have helped inspire the Arab Spring revolutions. Whether or not that is so, his plea bargain suggests that he is willing to be punished for some of the lesser crimes if the government will drop the major charge, of handing over state secrets to the enemy, a form of treason that could give him life in prison.

Manning argues that his treatment during his confinement over the past two and a half years has been punishment enough, particularly his conditions in Quantico, VA, where he was forced to sleep naked in his cell for a while. He was subsequently transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where he was treated much better than the Hofer brothers had been in 1918. His statements at his hearing last Thursday provide graphic details of what happened to him at Quantico. He was clearly not treated as harshly as the Hofer brothers had been, but he did endure mild torture.

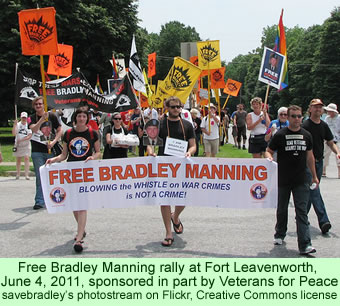

While his beliefs and the nature of the charges against him are very different from the Hutterite issues in 1918, his case has already prompted a lot of protests. His upcoming military trial, now scheduled for early next year, will pose challenges to Americans who follow the story. How much should the nation value people who violate laws in their principled opposition to the horrors of warfare? And perhaps more fundamentally, should the United States continue using warfare as a way of achieving its international objectives?

Comparing these two stories that frame the past century can inspire a bit of hope. The American army no longer tortures objectors to death as it did 94 years ago; it only inflicts relatively mild torture on soldiers who violate laws. Furthermore, to judge by the news accounts, there has been a lot more public opposition to the Quantico torture than there was to the events at Alcatraz and Leavenworth in 1918.

The contrast in the two news stories from last Thursday suggests that, in the long course of history, American attitudes may be slowly changing, toward torture and perhaps even toward warfare. It seems as if a huge nation like the U.S. can, indeed, change course. In the middle of the nineteenth century, some Americans violated their laws by harboring runaway slaves fleeing north toward Canada. And yet, within 94 years after the Civil War, monuments all across the American northern states celebrated so-called “stations” on the “Underground Railroad.”

Popular attitudes can change within a century, both toward lawbreakers who do what their values require them to do, and toward the moral issues they champion. The comparisons between the Hutterite story of 1918 and the Bradley Manning story of today can provide modest ground for hope.