Meni Mbugha, a Congolese man, has launched a career in Kinshasa designing fabrics based on the traditional art of the Mbuti, which they draw on bark cloth fabricated from trees. He learned about the traditional bark cloth art from his interactions with the Mbuti, and in return he is attempting to assist them in more effectively producing their own art for sale to tourists.

A news story last Wednesday, published on a website that focuses on news from the D.R. Congo and neighboring African countries, is a French translation, with modest changes, of the original English version published by Agence France-Presse in May 2014. The story described the way Mr. Mbugha, himself a Nande, prints fabric creations that are then turned into scarves, jackets, skirts and dresses to sell to tourists. Working in a small shop in Kinshasa, Mr. Mbugha draws his creations on a computer, the news story reports, before transferring them to fabric.

A news story last Wednesday, published on a website that focuses on news from the D.R. Congo and neighboring African countries, is a French translation, with modest changes, of the original English version published by Agence France-Presse in May 2014. The story described the way Mr. Mbugha, himself a Nande, prints fabric creations that are then turned into scarves, jackets, skirts and dresses to sell to tourists. Working in a small shop in Kinshasa, Mr. Mbugha draws his creations on a computer, the news story reports, before transferring them to fabric.

Mbugha, who is 33, was born into a Congolese family living in eastern France, one of four children of a father who was a nutritionist and a mother who was a housewife. When he was six, the family returned to the D.R. Congo, then called Zaire. The Nande, who live in the same general region of Congo as the Mbuti, traditionally had a close relationship with the Efe, another pygmy people.

Mbugha’s parents were not happy with his inclination, at first, to express his creative gifts in dance, then in styling. He studied computing for three years before enrolling in the fine arts at the Higher Institute of Arts and Crafts in Kinshasa. He became convinced that there is a connection between protecting the forest and fashion.

At that point in his life, in 2007-2008, he met an Mbuti family that had fled to Kinshasa from the militias, abuses and violence in the Epulu area of the Ituri Forest, in northeastern Congo. The family shared a book of photos with Mbugha that showed their traditional bark cloth drawings. He wondered why he couldn’t use those motifs on his fabric creations.

In 2011, he was able to visit Epulu and discovered that the Mbuti express their worldviews on the fabrics they make from the bark of the Ficus trees. Using red, yellow, and black pigments, Mbuti women depict on the bark cloths images based on the local flora and fauna. They are used in rituals and ceremonies, and the bark cloths are popular sale items to tourists and outside collectors. Mbugha felt that if the Mbuti could use fabric instead of bark cloth, they could make better money from the tourist trade.

He launched a brand of clothing in Kinshasa in 2012 called Vivuya, the funds from which he hopes will support his plans to launch a project called “Ndura,” which means “forest” in the Kibila language of Congo. He expects the project to give the Mbuti an additional way of earning money. He prepared an exhibition in Kinshasa at the French Cultural Institute and hoped, later, to have one in Kisangani, a large city in eastern Congo and nearer to Epulu. The exhibitions will hopefully promote an awareness of the arts of the Mbuti.

The bark cloth made by the Mbuti has been the subject of a fair number of publications, such as one in 2007 that analyzed the artistic merits of 14 different bark cloth paintings. It described the techniques the Mbuti use for making the cloth out of fig trees, the preparations of their pigments, and the ways they paint the cloth.

A book reviewed in 2006 described the role of the bark cloth art in the research work of Colin Turnbull, a famous American anthropologist, and Anne Eisner, an American woman painter who lived at the same time as Turnbull in Epulu, then called Camp Putnam. For both people, studying the Mbuti bark cloth paintings was an important facet of their work.

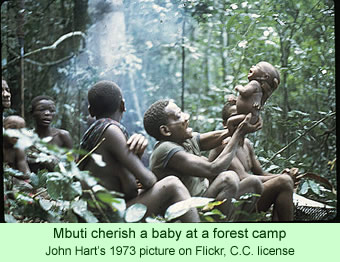

Turnbull went so far as to describe the importance of bark cloth in their society. More than an artistic endeavor, bark cloths were an essential element in introducing their infants to the peacefulness of forest life. In one of his articles, Turnbull (1978) maintained that a few days after birth, which normally would take place in the forest, the Mbuti mother would bring her infant out of her hut enveloped in some fresh, sweet-smelling bark cloth which she had made just a few days before. It was designed to be pleasing and smooth enough for comfort, but rough enough to introduce the child to the protection of the forest.

“Some Mbuti assert,” Turnbull (1978) writes, “that the first Mbuti were indeed born out of trees, so what could be more reassuring to the child than the smell and texture of a tree?” The anthropologist continues, “Once made, the mother may decorate the cloth with free-flowing designs painted with a twig dipped in the dark juice of Kangay, the gardenia fruit (p.170).”

The nature of the whole pregnancy and birth cycle, Turnbull continued, was a critical component in developing peacefulness in the child, since it initiated him or her into a strong faith, reinforced continuously throughout life, about the goodness of the world. The child would grow, in the traditional environment of the Ituri Forest, in total confidence that he or she would have support from both the human and the natural environments. Aggressiveness is not learned at the breast in a situation such as that, particularly when the child is swaddled in decorated bark cloth.