In the run-up to their hard-fought general election, won by Justin Trudeau and his Liberal Party on October 19, Canadians often expressed pride in their toleration for religious and cultural differences. Many Canadian commentators, and to judge by the results at the polls, a majority of Canadian voters, rejected what they felt were politics of divisiveness practiced by the Conservative government of Stephen Harper, and cited the fair treatment of the Hutterites as an example of inclusiveness. Many commentators also referred to the mostly-accepted rights of Hutterite women to dress differently.

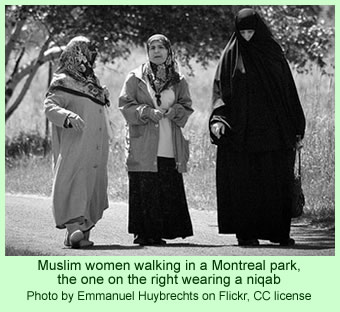

The battle in Canada, which became a major election issue in 2015, started when Zunera Ishaq, a 29-year old woman from Mississauga who is a former English literature teacher and a mother of four, was preparing to take an oath of Canadian citizenship in 2012. She had worn her veil, called a niqab, since she was 15, and she considers wearing it as a basic symbol of her beliefs in Islam. She wears it by choice.

The battle in Canada, which became a major election issue in 2015, started when Zunera Ishaq, a 29-year old woman from Mississauga who is a former English literature teacher and a mother of four, was preparing to take an oath of Canadian citizenship in 2012. She had worn her veil, called a niqab, since she was 15, and she considers wearing it as a basic symbol of her beliefs in Islam. She wears it by choice.

But she refused to take it off to swear in as a Canadian citizen—that would violate her religious beliefs. She deferred her oath-taking until her appeal could be decided in the Canadian courts. In February this year, the Federal Court of Appeals of Canada found the government’s ban on wearing a niqab during the oath taking to be unlawful.

Prime Minister Harper and his Conservative government unleashed a firestorm of political debate over the issue—he tried to have the decision delayed, but the courts denied the move. Ms. Isahq took her oath as a new Canadian citizen on Friday, October 9, ten days before the election. She wore her veil during the ceremony, a right she had won.

Mary-Ann Kirkby, who has written a couple books on the Hutterites and lived in a colony until the age of 10, spoke out about the controversy. She pointed out that Hutterites have endured criticisms comparable to those faced by the Muslim women with their niqabs. She described the not-so-sunny history of Hutterites in Alberta, when laws were passed prohibiting the sale of land for the purposes of developing colonies, which clearly discriminated against the Hutterites. She referred to those laws as “among the most blatant discriminatory pieces of legislation in Canadian history.”

Ms. Kirkby continued, “that is why the niqab issue raises so many red flags for me, personally. Canada is home to the highest concentration of Hutterites in the world, yet even today if a Hutterite woman had to take off her Tiechel [a polka-dotted head scarf] to swear an oath to become a Canadian citizen there would be no Hutterites in Canada.”

She continued that the traditional long dresses, long sleeved blouses, and head coverings of Hutterite females were all she knew as a kid. While she no longer lives in a colony or dresses in the traditional Hutterite garb, she said that Canadians should view the controversy over the niqab in the same light.

Controversy raged in the weeks leading up to the election. For instance, one writer opined that “by elevating the wearing of the niqab to a major election issue, Conservative leader Stephen Harper has fanned the flames of intolerance and bigotry in Canada for the sole purpose of driving a wedge between voters who feel uncomfortable that a woman would hide her identity for the sake of her or her family’s religious beliefs, and those who feel that no matter how strange and ‘un-Canadian’ it appears, it’s her right to do so.” Many editorials and letters to the editor of course defended the Harper government’s approach.

The polling itself on October 19 allowed Canadians to finally express their opinions about the government of Mr. Harper, and the opposition leader Justin Trudeau. Some voters appeared at the polling places wearing face coverings such as a wrestling mask, to vote—and to deride the government for its position on the niqab issue. In one polling place, an Elections Canada person told a protester that he would have to take off his mask, but the man responded by telling him how the regulations do permit him to vote. One man was photographed wearing a pumpkin to his polling place in Ottawa.

In a newspaper opinion piece last week, well after the voters had decided to turn Harper out of office, Alex McCuaig reviewed the history of toleration for the Hutterites as an example of how Muslim women should be treated. But he discussed “a few bumps in the road.” He described the Alberta requirement that driver’s licenses must have photos on them, even for Hutterites who refuse to have their photos taken. The Hutterites at a colony that protested the requirement went to court. That requirement was vetoed by the Alberta Court of Appeals in 2007 but that decision was overturned by the Canadian Supreme Court in 2009.

Mr. McCuaig argues that while that particular decision went against the desire of some Hutterites to have driver’s licenses without photos “there still [exist] a number of avenues in which their religious practices are accommodated that allow for separate schools, language education and rights to live communally. Alberta’s Hutterites are the archetype of religious tolerance and accommodation in this country,” he concludes. The interest in all of this is that, notwithstanding the controversies that have at times surrounded some of the Hutterites and their businesses, many Canadians appear to celebrate the colonies as examples of the toleration they cherish about themselves.

“If Canadians are open enough to accommodate Hutterites—whose first language is not English, French or a First Nations tongue—why is a cloth across a free-thinking woman’s face so distressful?” McCuaig concludes. Zunera Ishaq, he argues, “is more Canadian than most as she fought and won a battle for those who wish to see religious freedoms maintained in this country.”