The peaceful societies of India, like many people, struggle with the consumption of alcohol since it can promote social instability and violence along with providing a lot of pleasure. Of course patterns of alcohol usage vary among the peaceful societies of just that one country, from the Kadar men of Kerala, some of whom are reportedly becoming alcoholics, to the Paliyans of Tamil Nadu who strictly prohibit drinking—or at least they used to. A news story in The Hindu last week described the efforts of a Yanadi village in Andhra Pradesh to stem alcohol abuse by preventing a new liquor store from opening.

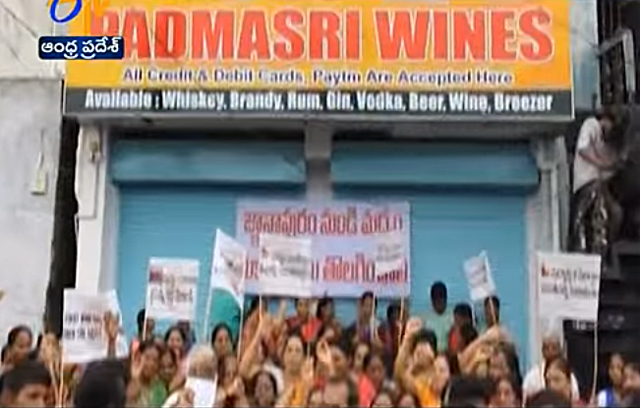

The Yanadi in the village of Marichetlapalem, near the town of Chimakurthy in the Prakasam District of the state, were alarmed when an entrepreneur attempted to open a liquor shop—often referred to as a “wine shop” in India—on a tract of private land near their community. The 50 Yanadi families in the village worried that readily available alcohol would disturb their peace and it would drain their family funds, according to P. Narasimhum, the leader of the village and the organizer of the protest movement.

The reporter spoke with numerous villagers. P. Padma said that the men of the village had a long tradition of abstaining from drinking. P. Kumari added, “we constantly live in fear of a wine shop coming up closer to our locality due to political pressure.” P. Venkayamma said that the people have very limited incomes and they are having a hard time making ends meet.

The people appealed unsuccessfully to the land owner to not sell to the wine shop. Protests to a variety of local officials went nowhere. But their appeal to the highest elected official in the district, the District Collector, Mr. V. Vinay Chand, was successful. He assured them that a liquor store would not be allowed in Marichetlapalem.

The Excise Superintendent for the district, T Srinivasa Rao, told The Hindu that in cases where protests are made against the opening of new liquor stores, he is asking the licensees to seek out alternative locations.

The Yanadi appear to have used less alcohol in the past than they do today, though there are some contradictions among the sources. Raghaviah (1962) wrote that they drank far less than a lot of other tribal societies and they are “a race of teetotalers by tradition (p.92).” Rao (2002), basing his work on the Yanadi of Sriharikota Island in the 1970s, mentioned a 35 year old man who had been left by his first wife because he had spent most of his earnings on alcohol.

It is clear from a more recent book by Agrawal, Rao and Reddy (1985) that changes were taking place. The authors described a group of Yanadi who participated in the festivals of neighboring non-Yanadi people and were frequent visitors to liquor shops. Once the Yanadi were moved off Sriharikota Island, they started earning better wages but they also started drinking liquor, which they did not normally have access to before then.

Stanley Jaya Kumar (1995) provided a still more recent, and a more comprehensive, examination of the Yanadi consumption of alcohol, particularly their fondness for a country liquor called “Saarai.” The beverage was made from thumma chekka, the bark of a tree translated from the Telegu simply as “Acacia wood,” with a sugar substance called jiggery added. The Yanadi frequently concluded their days with some of this preparation, sometimes the women having a drink with the men. During a major festival called “Dubhanku,” in addition to music and dancing, most of the Yanadi became intoxicated.

By the time of his investigation, the author noted that the consumption of alcoholic beverages had become normal for the Yanadi—an essential ingredient of their social milieu, though they normally drank liquor along with a few friends. However, Stanley Jaya Kumar contended, government officials have supported the expansion of drinking by the people, which has increased the revenues of the liquor distributors. The author ranted against the practices of liquor sales.

“Unfortunately, one of the worst forms of exploitation of the vulnerable tribals is the prevalent practice of liquor vending,” he wrote (p.89). He quoted N. K. Bose, who described liquor sellers as “agents of exploitation” of the tribal people. Stanley Jaya Kumar argued that selling liquor to the Yanadi communities “has brought disaster to the tribal economy” and it has “heaped untold miseries” on them (p.89). The liquor shops furthermore serve as conduits for anti-social elements from the so-called advanced parts of the country into the Yanadi villages.

The author argued, however, that an absolute prohibition of alcohol would not meet the needs of the Yanadi since consuming home-brewed liquor has long been one of their traditions. It is part of their religious rituals and it helps satisfy at least some of their nutritional needs. The basic point he made is that if they are aware of the dangers of addiction to alcohol, and if they are to control their consumption, they are the ones who need to take the initiative to do so. In some of the Yanadi tribal settlements, he noted, movements to stop the sale of alcohol had already started. The news story from The Hindu last week appears to be just the latest in a growing anti-liquor movement.