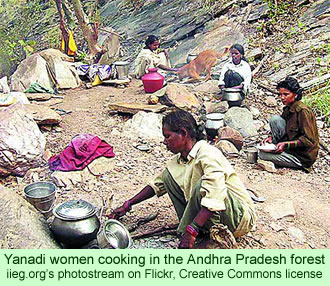

Forest officials in Madurai, in southern India, are preparing to include 16 Paliyan young people in a new eco-tourism venture in the mountains of western Tami Nadu state. According to a news report from the Times of India last week, the youths in the settlement of Kurinji, located about 27 miles west of the city near the Western Ghats, are being trained as trekking guides.

Forest Division officials have laid out three different trekking routes to scenic spots in the nearby mountains. One is to the Kutladampatti Falls 16 miles north of Madurai in the Sirumalai region, another is to Kiluvamalai near Natham, and the third is near Thottappanayakanur, a community close to their settlement. Nihar Ranjan, an official with the divisional forest, feels that with their experience hiking in these mountains, the young people will be well qualified to coordinate the trekking expeditions.

The recent plans fit in well with tribal development schemes and with a Tami Nadu biodiversity project. The new venture will also utilize the talents of physically disabled women who will prepare food packages for the trekkers. The department is planning to launch the project in February. Training began for the youths selected as eco-guides on Monday, January 5th. It focuses on techniques for leading and coordinating groups, interacting with tourists, and taking people out of the forests.

The fees collected from the trekkers will be used to pay the guides. Another news report, also by the Times of India, quotes V. Solairaja, a Paliyan youth who is the leader of the 16 trainees as saying, “We think this effort by [the] forest department will be of great help for us.”

According to Alex Mitham, the British Administrator of Tristan da Cunha, the homemade yacht named Way to Brisbane was sailing from the Netherlands to Australia when it ran into problems in the South Atlantic. It had last landed in Salvador, a city on the coast of Brazil, and was headed for Cape Town, South Africa. Piloted by Willem Klass Merten Van Rij, the sole occupant of the vessel, the yacht had a broken rudder, an engine that was not functioning, and some problems with its rigging.

According to Alex Mitham, the British Administrator of Tristan da Cunha, the homemade yacht named Way to Brisbane was sailing from the Netherlands to Australia when it ran into problems in the South Atlantic. It had last landed in Salvador, a city on the coast of Brazil, and was headed for Cape Town, South Africa. Piloted by Willem Klass Merten Van Rij, the sole occupant of the vessel, the yacht had a broken rudder, an engine that was not functioning, and some problems with its rigging.