Location. The volcanic island of Tristan da Cunha is located in the South Atlantic Ocean nearly 1800 miles west of Cape Town, South Africa. It was settled in the early 19th century by a British sailor and his family; other sailors, whalers, and women soon joined them to form the nucleus of the settlement.

Economy. About 260 people utilize small, relatively level portions of the island for farming and livestock. The islanders also fish and work at a lobster packing plant run by a South African firm. When the first fishing factory was established on the island in 1950, many of the islanders had a hard time adjusting to the introduction of money into their subsistence economy. It brought increased prosperity, but the islanders at the time preferred to rely on their traditional reciprocal exchange systems for their own social and economic interactions, and they adopted the practice of selling only a small amount of goods among themselves. They expressed resentment at the influence of money on their traditional values and the threat it posed to their relationships, integrity, and security. They have now adjusted to the money economy, though they still venture over to Nightingale Island periodically in their boats to harvest guano from around the penguin nests which they use to fertilize their gardens. Inaccessible Island, the other fairly large island close to Tristan, is strictly maintained as a wildlife preserve. In July 2011, the Marine Stewardship Council certified the rock lobster fishing operation as sustainable and well-managed, and in October 2014 the European Union opened its markets to Tristan lobsters.

Beliefs that Foster Peacefulness. The core values on the island are anarchy, absolute equality, and personal integrity. People who mind their own business gain prestige. Other values of the Islanders—kindness, consideration, peacefulness, and respect for the personal integrity of others—tend to shape their behavior; anyone who might break their code would suffer a considerable loss of prestige in the community. They take pride in their lack of crime, strife, or status distinctions. There is little sense of special privilege, and people lack authority, superiority, or influence over others. Throughout Tristan Island history, survival has meant, and still means to this day, freedom and personal integrity; these are higher values to them than affluence, material comfort, or physical sustenance. After the mass murder in Norway in 2011, the Islanders warmly expressed their condolences, exhibiting their compassion for a much larger, much better known peaceful society. They also display compassion when they generously provide relief for large-scale disasters, such as when a large cargo vessel went aground on a nearby island in 2011 and in 2013 when a typhoon smashed through the central Philippines.

Gender Relations. The family is strongly patriarchal; wives act in a very deferential fashion in the presence of male visitors. Except for a couple of reports of spouse abuse in the 1930s, men generally treat their wives kindly.

Raising Children. Children are expected to obey their parents’ directives, and they are subject to stern corporal punishment if they don’t. From 1961 to 1963, while the entire population of the island was in England due to an eruption of the volcano, the Tristan children interacted with other children in the British schools in a very shy and silent manner, a result of the general tendency of the Islanders to be taciturn. They tended to be passive and to lack aggressiveness, in contrast to the British children.

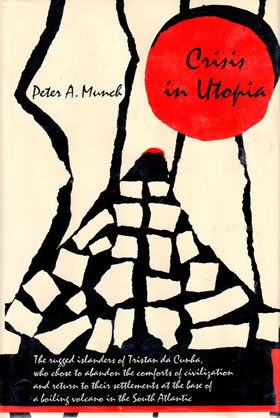

Social Practices. The Tristan Islanders are normally anarchistic and highly individualistic, but their habits were tested in 1962 when the British government decided to keep them in England permanently. They wanted to return to Tristan, but they did not know how to effectively unite, form a leadership group, and take decisive actions. Faced with this crisis, they delegated some leaders to send petitions to the proper administrators, and, when they went unanswered, they held a group meeting. When the administrators realized the Islanders were determined to find their own way home, the Colonial Office backed down and permitted them to return to the island. In effect, the anarchistic values and practices of the Islanders had given way, for the first time in their history, to group action—but they soon returned to their normal ways when they got home.

Sense of Self. The islanders are quite conservative and resistant to change. They relate to others with a mixture of helpfulness and deference. They attach great importance to maintaining their personal dignity, and they used to refuse to drink alcohol, even if offered to them by visitors, because they did not want to lose control. However, Glass reports in his book Rockhopper Copper that the Islanders are now using alcohol to some extent, which worries him. In 2015, an advertisement was posted for an Alcohol Counsellor to help out with problem drinking on Tristan. The Tristanians value their independence, economic self-sufficiency, and personal freedom. They tend to repress self-assertion and evince a strong respect for others.

Cooperation and Competition. When the Tristan Islanders were forced to move to Britain in 1961, they had virtually no knowledge of competition—their peacefulness is based, at least in part, on their highly cooperative attitude toward one-another. While they are theoretically independent of one another, in practice they cooperate in a number of economic endeavors. For instance, launching a long boat into the ocean swells takes a crew of people, and bringing home a heavily loaded boatful of meat or produce from another part of the island can only be accomplished cooperatively. However, a news story in 2012 indicated that the people of Tristan da Cunha have become enthusiastic about competitive sports.

Social Control. Teasing and ridicule are important parts of the socializing process on Tristan—a subtle means for asserting community moral values, informally communicating, and asserting social control. While they constantly gossip about one another, they avoid any open conflict.

Social Control. Teasing and ridicule are important parts of the socializing process on Tristan—a subtle means for asserting community moral values, informally communicating, and asserting social control. While they constantly gossip about one another, they avoid any open conflict.

Strategies for Avoiding Warfare and Violence. One of their primary strategies for avoiding violence and conflict is nonviolent resistance. A good example of this strategy occurred in the 1930s when they had to cope with an imperious, dictatorial minister who tried to run their lives. They could never confront him; they would always buckle under to his will with a meek “yes, Father,” out of respect for his power and high office. But they did perfect the practice of nonviolent resistance by accepting his orders as much as necessary to placate him—and ignoring everything else that they could get away with. They felt that his actions were simply part of the fun he enjoyed in being among them. Besides, in a few years another minister with different ideas would probably replace him.

But How Much Violence Do They Really Experience. The highest level that hostility reaches on the island is that occasionally two people will stop talking to each other, but they normally can’t maintain even that level of tension very long. Quarrels are rare and fights have not occurred in living memory. The person who lost his temper in a quarrel would have that scar on his reputation for life, while someone who diffused a tense situation with a joke would gain general respect. The island policeman, Conrad Glass, was quoted in a news story in 2010 as saying that the most recent fight occurred in the 1970s among the sailors on a foreign fishing vessel.

Scholarly Resources in this Website:

- “Culture and Superculture in a Displaced Community: Tristan da Cunha.” (Munch, 1964)

- “Atomism and Social Integration.” (Munch and Marske, 1981)

- “Return to Utopia.” (Snyder, 2006)

More Resources in this Website:

- The Tristan Islanders enjoy their holidays and festivals, such as the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth in 2012, the Old Year’s Night every December 31st, and an annual “Ratting Day” in May, in which the Islanders spend time reducing the population of alien Norway rats—and make a holiday of it in the process.

- The Islanders have reconstructed a traditional thatched roof dwelling in the settlement on Tristan, both to show visitors and to preserve their traditions for their own future generations.

- The funeral customs of the Islanders were described in a news story in 2014.

- Tristan has a small hospital and a medical doctor, but providing modern health care on the remote, inaccessible island presents challenges.

- The Royal Institute of British Architects opened a worldwide competition in March 2015 soliciting creative designs for a more energy efficient community on Tristan.

Sources in Print: Glass 2011; Keir 1966; Loudon 1966, 1970; Munch 1945, 1964, 1970, 1971, 1974, 2008; Munch and Marske 1981

Sources on the Web: Wikipedia (English Version); Tristan da Cunha; Peter A. Munch/Tristan da Cunha Collection; Tristan da Cunha Association

Updates—News and Reviews:

Selected Recent Stories

January 14, 2016. Tristan Parties in the New Year

July 30, 2015. Tristan Has No Crime

January 8, 2015. Review of the Tristan Year

March 27, 2014. Presentation on Tristan Coming to Toronto Area Library

All Stories

All stories in this website about the Tristan Islanders are listed in the News and Reviews Subject Listing