The news about Tristan da Cunha last month was dire. A huge ship had crashed on a reef near Tristan, threatening not only thousands of sea birds but the economy and social traditions of the Tristan Islanders as well.

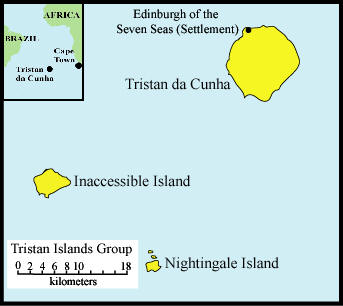

On March 16th, the MV Oliva, a 75,000 ton bulk carrier taking a load of soy beans from Brazil to Singapore, crashed head on into the rocky coast of Nightingale Island, part of the Tristan Group, about 19 miles (30 kilometers) southwest of the main island of Tristan da Cunha. Nightingale and nearby islands had millions of nesting sea birds. Some were soon covered with oil that escaped from the wreck.

On March 16th, the MV Oliva, a 75,000 ton bulk carrier taking a load of soy beans from Brazil to Singapore, crashed head on into the rocky coast of Nightingale Island, part of the Tristan Group, about 19 miles (30 kilometers) southwest of the main island of Tristan da Cunha. Nightingale and nearby islands had millions of nesting sea birds. Some were soon covered with oil that escaped from the wreck.

Most of the news reports since March have focused on efforts to clean oil off the birds. Sean Burns, the Administrator of Tristan da Cunha, issued a comprehensive report last Thursday summarizing the status of many of the issues facing the Islanders as a result of the shipwreck.

Apparently, cleaning efforts for the rockhopper penguins and the other seabirds coated with oil have continued, and will go on after the current flotilla of ships leaves. The lead for the cleaning is being provided by a nonprofit seabird rehabilitation center in Cape Town called the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds (SANCCOB). Burns writes that the SANCCOB team is planning to leave at the end of this week, April 22 or 23, but he indicates that there may be a possibility of extending their stay.

The SANCCOB website says, in an undated news post, that 3,718 oiled penguins have been captured and transferred to Tristan for cleaning. Fortunately, most of the seabirds had just finished raising their young and many had left their rookeries by the time of the wreck. The birds will not return to the Tristan Islands until August to begin the next breeding cycle. If it had happened a few weeks earlier, the disaster for the wildlife could have been much worse.

Burns writes that five ships are, or were when he wrote, anchored off Tristan—a record, he feels. One of the ships has a helicopter which has flown over Nightingale and the other islands. There was little evidence of oil around Inaccessible Island, one of the world’s major seabird sanctuaries, but there was still a lot of it around Nightingale and its nearby islets. The wreckage of the ship has disappeared beneath the waves, but Mr. Burns has been told that as it breaks up, the wreck will probably continue to release pockets of oil into the seas. Burns indicates he is eager for the storms which sweep the region to clean away the oil and soy spilled from the wreckage.

Workers are trying to clean the beaches on the islands, but they are apparently not using any chemicals or dispersants. They are using high-pressure hoses with warm sea water. Any oil they can successfully clean off rocks is being bagged and removed to Cape Town. None of it, he claims, will be allowed to get back into the water.

The fishery around Nightingale and Inaccessible has been closed. Fishery samples are being sent to Cape Town for analysis. Mr. Burns writes that he is working with the owner of the fishing operation, Ovenstone, a Cape Town firm, plus insurers to resolve the insurance issues.

He also says that all islanders who have pitched in to help during the crisis should be continuing to keep records of the time they are spending, since the insurers should be compensating people for their labor. He will be seeking compensation for possible longer term declines in the lobster fishery as a result of the shipwreck.

The Tristan Islanders are quite used to dealing with maritime disasters. News reports earlier indicated that they immediately took in the seamen from the sunken vessel, as they have done for generations when ships wreck on their shores. Burns writes, in that spirit, “many thanks to all of you for pulling together during this crisis. The response from the community has been fantastic.”