A number of Hutterite colonies in Manitoba are hiring non-Hutterites as employees in their manufacturing businesses, which is beginning to change their economic and social relationships. The Winnipeg Free Press explained the development in a news story on May 5.

The largest enterprise cited by the news service is a company called Springfield Woodworking, owned by the Springfield Hutterite Colony, which is located a short distance east of Winnipeg near the town of Anola. The workforce of the company includes 60 people, three-quarters of whom, 45, are non-Hutterites. Springfield Woodworking is a kitchen and bathroom cabinet manufacturing firm, the third largest in the province.

When Pauly Kleinsasser, the general manager of the firm, hired his first employee from outside the colony 15 years ago, he wasn’t even sure how to prepare his paycheck. Members of the Hutterite colony are not paid for their labor and do not have personal bank accounts—everything they need is provided by the group. Since then, Kleinsasser has mastered the techniques for handling the payrolls as well as the benefits packages for the non-Hutterite employees.

Kleinsasser told the reporter from the Free Press, Ruth Bonneville, that the colony could not handle such a large operation with its own people. They have 100 members, farm 7,500 acres of land, and maintain a hog finishing operation. “We’re short-handed on the farm side as it is,” he told her. He said that the manufacturing company is growing rapidly; it may expand its operations again next year. It now makes 13 kitchens per day, roughly 3,500 per year.

He was proud to show the reporter a jersey from the Winnipeg Jets, a professional hockey team from the city. His company installed a kitchen in the home of one Kevin Ceveldayoff, the general manager of the team, a couple months ago. Kleinsasser told Ms. Bonneville, “We’re doing kitchens for a lot of high-profile people.”

It is clear from the article that the success of the enterprise is due in part to the business acumen of Kleinsasser. He and an uncle, the Hutterite minister Ruben Kleinsasser, started the business by making bedroom furniture in the colony shop for outside neighbors. They branched out into making kitchens when a neighbor pressured them into making one for him. Ruben has subsequently left the company but Pauly continues to manage it.

It doubled in size seven years ago when Pauly decided to move the company showroom to an industrial area of Winnipeg. The cabinets are quality products, apparently, with thicker wood for the bottoms of their drawers than the ones made by their competitors, and they have a special, hardened, coated finish on the outsides of the cabinets. An expert in the business credits the success of the company to the workmanship and quality of their products.

Several other colonies in Manitoba are hiring outsiders in addition to Springfield, including the Crystal Spring Colony near Ste. Agathe—it employs up to 10 people to work in Allsons, a welding firm that serves the Crystal Spring Hog Equipment Company on colony grounds. On the Oak Bluff Colony, a company called EcoPoxy has five employees who are not Hutterites. The Acadia Colony near Carberry has five staff member who are not part of that colony working at its Community Truss business, a firm the makes trusses for roofs and floors. Non-Hutterites work in a manufacturing operation at the Heartland Colony near Hazelridge, not far from Springfield.

The reporter mentioned that a common complaint in Manitoba against the Hutterites has been that they do not provide many economic benefits to their rural neighbors. They tend to be self-sufficient, buying what they need in bulk from major jobbers in urban centers. But as the colonies are expanding their manufacturing enterprises beyond the capacities of their own members, they are changing the dynamics by hiring outsiders.

The expanding business enterprises are also changing the population dynamics within the colonies. While they have traditionally tended to form new colonies when they reach a population of 120 to 150, that may be starting to change. Due to economic forces beyond their control, such as the prices of farmland, they have turned to manufacturing, which is allowing them to grow somewhat larger and not subdivide quite so often.

Mr. Kleinsasser made a comment to Ms. Bonneville about the relationship of colony size to keeping the internal peace. “With manufacturing, now colonies can get up to 200 people, if peace can be kept,” he said to the reporter.

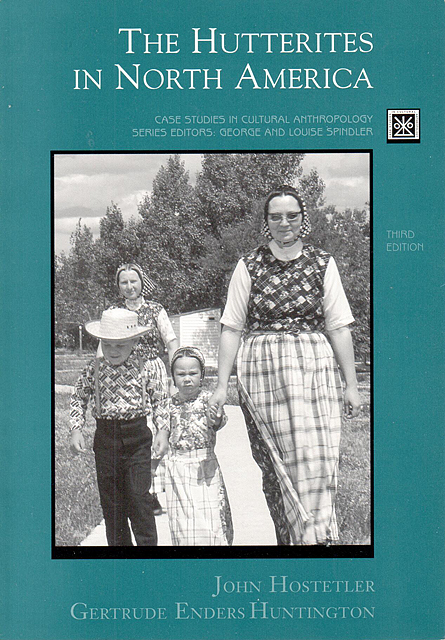

Many books about the Hutterites discuss the issues involved with the expansion of the colonies and the formation of daughter colonies, a good example being Hostetler and Huntington’s classic overview (1996). That work describes how colonies tend to divide about every 14 years: land is purchased, buildings are erected, and a daughter colony is formed. In order for the new colony to begin functioning it should have a minimum of 60 people, half of whom are children under 15. About 15 people selected for the new colony should be working males; of them, 5 may be over 25 years old and able to handle leadership positions. The remaining 10 would be younger, unmarried, and unbaptized.

Many books about the Hutterites discuss the issues involved with the expansion of the colonies and the formation of daughter colonies, a good example being Hostetler and Huntington’s classic overview (1996). That work describes how colonies tend to divide about every 14 years: land is purchased, buildings are erected, and a daughter colony is formed. In order for the new colony to begin functioning it should have a minimum of 60 people, half of whom are children under 15. About 15 people selected for the new colony should be working males; of them, 5 may be over 25 years old and able to handle leadership positions. The remaining 10 would be younger, unmarried, and unbaptized.

The new colony has a lot of work and little competition for major positions. As it matures, however, the colony may have 120 to 130 people, of whom 35 are males over 15; 16 men may be over 30 and have lifetime appointments to all the major positions. But here is where Mr. Kleinsasser’s worries come into play. The five men between 25 and 30 would have no chance for upward mobility. Competitive feelings can and do develop in these larger colonies, especially between families, and fathers will try to get favorable positions for their sons. Competition begins to breed social problems. Factions and cliques tend to form.

The branching process disrupts this competition and channels it into the expansion of the old colony into two new ones, one of which will stay on the old property. When everything is working according to tradition, the entire colony works for several years to find an appropriate site for the new colony and to develop the infrastructure. When it is time to branch, the men divide the families into two groups, balancing all known preferences and abilities, with the two groups headed by the preacher and the assistant preacher. Everyone packs and the choice is made by lot as to which group will stay and which will move. Thus the peacefulness will be maintained. Mr. Kleinsasser is wise to be concerned about the future.