An Amish couple has settled a lawsuit against the U.S. federal government with guarantees that their freedom from being photographed will not be abrogated. The Indianapolis Star published an account of the historic agreement on May 29.

Since Old Order Amish religious beliefs prohibit self-promotion, they were listed in the lawsuit only as “John and Jane Doe.” Their situation is that John, the father of 11 children and a U.S. citizen, lost his first wife when she died due to complications in childbirth. In 2014 he married Jane, a Canadian who had entered the U.S. legally. The couple has since had two more children. The 15 members of the family live in an Amish community in Southern Indiana.

In January 2015 Jane decided to apply for permanent residency status so she could continue living with her large family. She and John submitted all the paperwork and documents as needed except for the personal photographs the forms required. The couple also completed the required immigration interviews. But they refused to supply personal photographs, which would violate the biblical prohibition against making graven images of oneself (Exodus 20:4). They deeply believe in that stricture—it’s prohibited by the Bible and it might lead to self-promotion.

Her application was denied despite the fact that she had willingly provided other biometric information such as her finger prints. Being denied residency, Jane faced leaving her husband and family and returning to Canada or her family moving up to Canada to live with her.

The newspaper contacted Michael H. Sampson, one of the attorneys for the couple. He said that the Amish are highly opposed to fighting in court. “They never wanted to go through this,” he said. He expressed the hope that as a result of the court settlement, other Amish people would not have to go through what the Doe family has experienced. He added that initially the government officials “didn’t pay attention or take the matter seriously.”

After their initial negotiations with the agencies involved—the Department of Homeland Security and the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service—failed, the couple decided to sue them in the US District Court for the Southern District of Indiana. They complained that the agencies and the officials in them were violating their rights to freedom of religion, of speech, and of association.

Subsequent negotiations handled by the pro bono efforts of the Reed Smith law practice in Pittsburgh secured a waiver from the government of the requirements for the photograph. Ms. Doe has now been cleared to have her permanent residency approved. Procedures for her to travel back and forth between her Indiana home and her extended family in Canada have also been agreed upon. The settlement stipulates that she will only have to show her permanent residency card and the agreement signed by the government in order to cross the border.

Attorney Sampson concluded for the newspaper that John and Jane are just like any other parents—they want to care for and love their children. “My clients are just thrilled to have this resolved” he said. “It means they can be a family — that’s what they wanted.”

The news story suggests that the Amish refuse to be photographed not only because of the Bible but also in order to promote personal modesty. Avoiding self-promotion with the goal of strengthening a peaceful social order is not unique to the Amish, however: social scientists have noted a number of similar strategies among other peaceful societies. A few selections from the literature will illustrate how comparable strategies can help people minimize discord in order to achieve reasonably conflict-free societies.

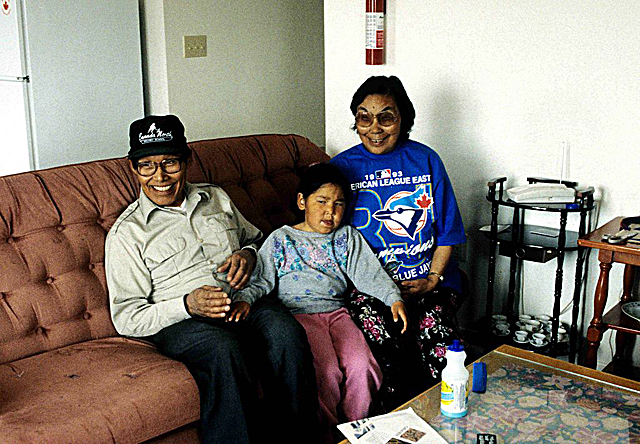

For instance, the Inuit strategy is for individuals to be very modest, cautious, and reticent about their own accomplishments. Also, they avoid making direct requests. According to Briggs (1994), if they have to request something, they turn it into a joke so that a confrontation is avoided and a denial is part of the joke. Furthermore, they do not make invitations or promises; they do not ask questions of other people, particularly the question “why,” either about the way others feel or what their plans may be.

Munch (1945) wrote that the Tristan Islanders repress self-assertion and evince a strong respect for others. The major principle guiding the relationships of the islanders with one another is a strong sense of self-respect and mutual helpfulness. They attach great importance to maintaining their personal dignity, and refuse to drink alcohol even if offered to them by visitors. Their considerate, kind behavior toward one another justly earns them a reputation as being “one of the most peace-loving people on earth,” Munch wrote.

Several anthropologists have written about the way the Ju/’hoansi avoid self-promotion, though Lee (1978) may have captured it best. He wrote that leadership qualities vary among them: some leaders are excellent speakers, some have strong personalities, some have gruff personalities, some are charming, some are mellow and some are soft-spoken. They share no common traits except that they are never aloof, boastful, overbearing, or arrogant, characteristics that they can’t accept.

The traditional leaders recognize the absolute equality of everyone and exert their leadership through indirect and subtle means. However, according to Lee, contact with the larger political realities of dealing with outside groups and representatives of modern southern African nations have required them to accept leaders who, in order to deal effectively with the outsiders, must be aggressive and articulate. The characteristics of the new leaders have thus become completely different from, and represent a denial of, the traditional leadership qualities of generosity, modesty, and egalitarian behavior.

And finally, the Paliyans maintain order and resolve conflicts through the use of several social and personal mechanisms. The first mechanism is self-restraint—the repression of anger and expressions of hostile feelings. In order to achieve this, they avoid the consumption of alcohol, which they feel would make them aggressive. According to Gardner (1972) they dissipate anger by applying to their foreheads sirupani pu, or “laughing flower.”

Whether people apply special flowers to their foreheads or refuse to allow photos of their faces, societies that have a strong desire to avoid conflicts and anger that might lead to violence have evolved a variety of methods of fostering personal restraint. The Amish are not the only people with unique approaches to building peacefulness.