The economic situations of two separate groups of Yanadi were described in starkly differing terms last week, as one community has been suffering extreme privation while the other is beginning to prosper.

A news report in The Hindu described a group of 16 bonded Yanadi laborers, people who, with their families, had been held in servitude for decades by unscrupulous upper caste people. The news report does not name the caste or family who “owned” the laboring people. Several NGO representatives reported the situation to local government officials in the Nellore District of Andhra Pradesh, and the local official ordered an immediate inspection of the remote Yanadi village.

Representatives for the two NGOs involved, the International Justice Mission and the Association for Rural Development, found that the laborers, including children, were required to work 18 hours per day, 6 a.m. to midnight. They had to walk into forests and collect branches to be sold by their owners. They were forced to produce bundles of the branches amounting to hundreds of kilos every day. For their work they were paid Rs.500 (US$8.00) every two weeks, far below a living wage.

The victims reported that even children as young as eight years old, who were born into bondage, were forced to gather the sticks. They had never attended school. One child was afflicted with seizures, so the family was pushed further into debt in order to pay for the child’s hospital care.

The NGOs discovered the situation and, upon further inquiry, they were told that some of the laborers had been loaned Rs.13,000 in 1994 and had become bonded laborers as a result of those debts. The man who had originally lent the money later sold the laborers to the recent owners. Those people would not permit the Yanadi to leave the premises or to work for others. On occasions when men were permitted to return to their native villages, they could only do so if they would leave behind family members who would serve as collateral.

Abishek Joseph, the team leader for the International Justice Mission, reported on a conversation with a Yanadi. “I talked to a man in his twenties who said his family came there when he was only a small boy. I cannot imagine what it is like to grow up like that, but at least now his kids won’t have to.”

As a result of the intervention by the NGO staff members, the government officials issued release certificates for the 16 indentured Yanadi, which entitle them to Rs. 1,000 each for support. An additional three children and their families were also rescued from the situation.

The Hindu has also covered the implementation of an innovative program from India’s National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) in the state of Andhra Pradesh (AP), an effort which was designed to help poor tribal people become more successful in agricultural endeavors. The agency began what it called the “Maa Thota” program in a rural AP village in May 2011.

According to a news story at the time, the project would ultimately benefit 30,000 tribal families over the course of seven years. The point of the effort was to provide agricultural facilities and training for the tribal farmers. It also assisted in bee keeping, dairy production, and various kinds of horticultural efforts.

Another report in The Hindu just two months ago about Maa Thota indicated that it has already improved the lives of 2,100 tribal families in AP, many of whom live in infertile, hilly areas of the state. The newspaper reported on the training given to tribal people on advanced technologies that would foster higher yields from their crops. Some of the farmers were reporting up to Rs.30,000 (nearly US$500) income per year from growing vegetables, amla fruits, cashews, and bananas.

Finally, a news report last week described the successes of the Maa Thota program among some Yanadi farmers in the Chittoor District of the state. A Yanadi man named Doraswami is described by the reporter as proudly owning, along with 50 other Yanadi families, a successful orchard of mangos and amlas, developed with the assistance of the program.

Doraswami worked as a contract laborer for 20 years in various places but he finally sold everything he owned in order to buy a few acres of land and settle in the village of Thimmayagaripalli in 2007. Along with the other Yanadi in the new settlement, he tried to cultivate land around the community, but he failed. However, in 2008, he planted 43 mango and 44 amla trees on his acre and began to investigate more advanced horticultural techniques.

Officials representing the Maa Thota program offered their assistance in 2009, if the 54 families were willing to pool their labor and work as a team, raising one acre of crops per family. They bored four holes for water and the program provided the mango and amla plants for the entire community orchard. They also planted, on the edges of the orchard, agave, teak, seethaphal, and curry leaf plants. According to the reporter, out of 60 Yanadi farming families now, 50 of them have half an acre of mangos and half an acre of amlas.

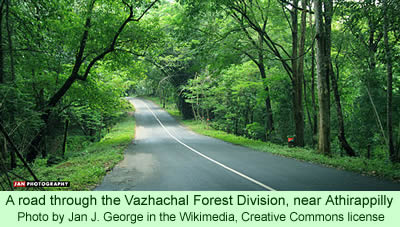

However, as the plants are getting to the point where they are starting to produce fruits, the Yanadi are becoming worried about the fact that there is no road to their orchard. Their concern is that they are expecting to harvest 50 to 60 tons of fruit this season. They are asking officials to develop a 1 km road into the orchard so they can transport their produce to markets. They are also requesting electric power for their four bore holes so they can upgrade their water sources from hand pumps to a better, drip irrigation system.

Doraswami has evidently led the local Yanadi people into accepting and developing this new orchard, and he and his wife have been recognized for their successes.

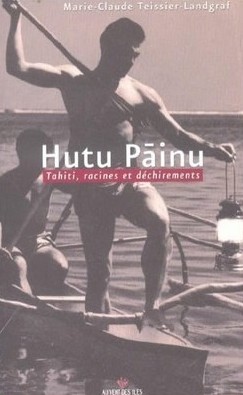

The opening of Hutu Pāinu describes the arrival in Tahiti of a young girl, Sophie, with her French mother, Amélie, on a ship from war-torn France immediately after World War II. They have come to Polynesia to be with the girl’s Tahitian father. Contrasts between the cultures of France and of Tahiti quickly become apparent in the different ways the major characters understand humanity.

The opening of Hutu Pāinu describes the arrival in Tahiti of a young girl, Sophie, with her French mother, Amélie, on a ship from war-torn France immediately after World War II. They have come to Polynesia to be with the girl’s Tahitian father. Contrasts between the cultures of France and of Tahiti quickly become apparent in the different ways the major characters understand humanity.