Photojournalist Tanmoy Bhaduri provided an upbeat assessment last week of an Anganwadi center, located in a Birhor community in a remote corner of India’s Jharkhand State. He met a Birhor woman who is trying to improve the health and nutrition of the women and children in the village, the primary mission of India’s Anganwadi centers.

Pinky Birhor is employed by the Anganwadi center at the unnamed colony, which has about 100 families living in it. Her biggest challenge has been to get pregnant women and lactating mothers to come into the center for health exams. The women are scared of medicines and injections because of their beliefs, Pinky said. She added that Birhor rituals require pregnant women to stay in their leaf huts, cut off from the world, and to deliver their own children.

“I would say my biggest achievement has been to get the women to the hospital for their delivery. There was a lot of resistance but once a few women came back with healthy babies, they started believing in me,” Ms. Birhor told Mr. Bhaduri.

One of the pregnant mothers confirmed the value of Pinky’s work. She told the writer that part of the problem is that workers from other sectors of Indian society may have strong prejudices against the untouchable adivasi people. “The worker who was here before Pinky wouldn’t even touch the children. How can you take care of them if you can’t even touch them? We trust Pinky because she is one of us. She wouldn’t do anything to harm our kids or us,” the woman said.

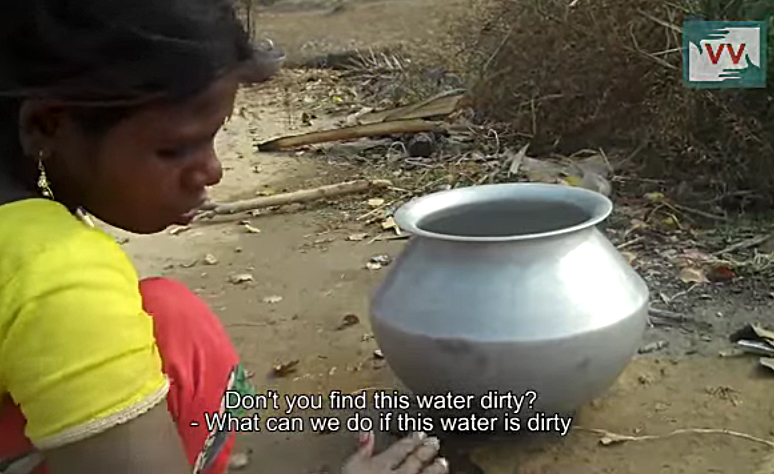

Pinky also has made a successful beginning in her campaign to convince the Birhor in the community about the importance of cleanliness. She says it is easier to imprint new ways of acting on the children. She insists that the kids take baths before coming to the Anganwadi center and she requires them to wash their hands before eating breakfasts, habits that the adults don’t have, at least not yet.

Another cause that Pinky has taken up is getting enough food for the colony. The Anganwadi program provides only a minimum amount of food for the residents; with help from a local NGO she has gotten the Birhor involved in gardening so they can grow their own vegetables. She tells Bhaduri, with obvious pride, that the children are now getting enough nutrition. “You can see it helps because they fall ill less often,” she brags to the journalist.

He is clearly impressed by Ms. Birhor. Despite not having enough financial support for the needs of the preschool children and the mothers in the colony, she does not give up. “These are our kids. They will grow up to become the future of this community. I cannot let their future be affected,” she asserts.

The author generalizes about the Birhor in this colony that they are “still surviving on their hunting and gathering skills,” though the only additional information he provides about their economic pursuits is his brief narrative about the recent gardening venture that Pinky inspired. An Indian anthropologist, Rajesh Pankaj (2008), provided more details about the economic activities of the Birhor in Jharkhand. He found during his fieldwork from 2002 – 2005 that representations of the Birhor as simply hunters and gatherers are no longer correct.

A few have taken up agriculture but not too many. However, it is safe to say that many are shifting at least some of their economic pursuits to part-time laboring on farms, to working in local industries such as brick kilns, and to pulling rickshaws. While hunting and gathering remain the primary source of food for most of them, they are not exclusively foragers any longer.