Stanford Zent describes the ethnic boundaries and inter-group relationships of the Piaroa during their pre-colonial, postcolonial, and modern historical periods as generally, though not always, peaceful. His essay, published last year in an edited volume on indigenous mobility and migrations in Amazonia, provides a useful history of Piaroa inter-tribal social relations.

After establishing the theoretical background of his research, he dives into an analysis of Piaroa relations with other Indian tribes during the pre-contact period. He writes that the pre-colonial Piaroa appear to have had a lot of contact with surrounding groups. Evidence found in burial sites, pre-historic ornaments, surviving rock art, and other archaeological bits and pieces suggest that they had extensive inter-group contacts.

After establishing the theoretical background of his research, he dives into an analysis of Piaroa relations with other Indian tribes during the pre-contact period. He writes that the pre-colonial Piaroa appear to have had a lot of contact with surrounding groups. Evidence found in burial sites, pre-historic ornaments, surviving rock art, and other archaeological bits and pieces suggest that they had extensive inter-group contacts.

Their oral histories also imply that they had a lot of contacts with outsiders, but they appear, to judge by the stories, to have been complex interactions, alternately peaceful and symbiotic, then competitive and hostile. At times they traded, at other times they raided. They did have close, peaceful, trading relations with several large, neighboring groups, such as the Maipure and the Atures. Those tribes lived in the floodplains, while the Piaroa lived in the headwaters, of the same rivers. Statements by Piaroa sources differ as to whether they intermarried with those outside groups, some indicating they did and others that they did not.

Their pre-contact relations with other neighboring groups appear to have been not as friendly. The Piaroa may have had some physical conflicts with the Mako, the Yabarana, and the Mapoyo; without doubt they traded shamanistic witchcraft attacks back and forth. There are some records of physical hostilities with those groups before the European conquest.

The Piaroa, during the pre-conquest period, had a complex social organization, which included numerous clans associated with different areas in the Middle Orinoco territory where they lived. While the clans shared the same language, their physical characteristics appeared to have differed a bit. They did trade extensively.

When the Europeans arrived, the newcomers soon destroyed the more riverine societies, peoples who lived in villages that were easily accessible to slave raiding and warfare along the main waterways. The Piaroa were mostly spared from those genocidal attacks because they lived in headwaters areas, far from the Orinoco and its major tributaries, in places that were protected by thick jungles and small rivers with large rapids. The Piaroa also feared raids by traditional enemies from outside the Middle Orinoco region, predatory Indian groups such as the Caribs and the Arawak peoples.

The Piaroa were especially afraid of the diseases that newcomers brought into the forests of Venezuela, epidemics which wiped out other Indian populations. Their fear helped keep them isolated from outside contacts for many years. These fears prompted them to move still farther into inaccessible headwaters areas.

As the downstream tribes, the Atures and the Maipure, were exterminated, however, the survivors of those groups appear to have moved upstream to settle among the Piaroa bands and intermarry. In time, the Piaroa slowly began moving back downstream, occupying territories in the lower streams and river basins that other Indian groups had abandoned, or where they had been exterminated. As the Piaora territory expanded, it assimilated non-Piaroa into their growing communities.

“In any case,” Zent emphasizes, “the territorial expansion of Piaroa was accomplished by peaceful means, essentially through intermarriage and co-residence (p.179).” He argues that violence and destruction during the earlier conquest years fostered a lot of inter-ethnic difficulties, but the settling of the frontier allowed social relations to pacify and the peaceful expansion to take place.

In the modern period, starting about 1960, drastic changes occurred in Piaroa society. Missionaries from the New Tribes Mission penetrated their communities, and the Catholic Silesians established boarding schools in some of their villages. In the 1970s, the Piaroa migrated downriver, to be nearer health clinics, social welfare offices, and economic opportunities. By 1982, when the first census of Venezuelan Indians was conducted, most of the Piaroa communities were located along navigable rivers, and village populations were mostly over 50 people—much larger than the traditional hamlets of 25 to 30. By 1992, the peaceful migrations decreased, as the settlement patterns became more stabile.

These recent migrations caused crowding and stresses in the more urbanized communities. In addition, other peoples have settled among them. These conditions have fostered tensions and conflicts over access to land and resources. But as a result of their downstream migrations, the Piaroa have become successful traders of forest products and cash crops. At the same time, they have become consumers—electrical appliances, fabricated clothing, tools, cooking utensils, and the like.

Many other changes have permeated Piaroa villages in recent decades. The authority of the shamans, traditional leaders of the communities, has been taken over by younger and more Westernized leaders. Piaroa business people, civil servants, and political operatives are able to negotiate the intersections of local concerns with national and international forces better than their predecessors could have done. Inter-tribal organizations have sprung up to coordinate the resolution of common problems. Zent effectively summarizes for non-specialist readers the complexities of overlapping, interacting, and sometimes contradictory political organizations and social forces that seek to secure indigenous rights within a broader landscape of Venezuelan politics and society.

Zent, Stanford. 2009. “The Political Ecology of Ethnic Frontiers and Relations among the Piaroa of the Middle Orinoco.” In Mobility and Migration in Indigenous Amazonia: Contemporary Ethnoecological Perspectives, Edited by Miguel N. Alexiades, p. 167-194. New York: Berghahn Books

News stories

News stories  A year ago, after ten years of support, Father Gutierrez felt inundated by the increasing demands by residents of the many different Zapotec communities in L.A. for more celebrations. He resigned and moved to a church in Baldwin Park. Another open-minded priest, Father Arturo Corral, has taken his place. The tradition of accepting, and hosting, the village festivals continues to grow.

A year ago, after ten years of support, Father Gutierrez felt inundated by the increasing demands by residents of the many different Zapotec communities in L.A. for more celebrations. He resigned and moved to a church in Baldwin Park. Another open-minded priest, Father Arturo Corral, has taken his place. The tradition of accepting, and hosting, the village festivals continues to grow.

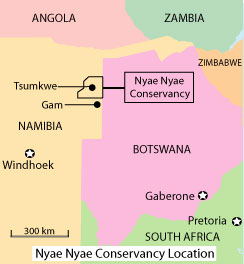

An elderly Herero man reportedly answered, “What will you have us do? Return to Gam to die?” The chief told him that they needed to obey the laws of their country, which do not allow them to move into Tsumkwe like that. “I as a San person respect that law. Why will you not respect that law?” he told him. According to Namibian law—the Traditional Authorities Act 25 of 2000, and the Communal Land Reform Act 5 of 2002—the traditional chief has the sole authority to determine the right to residency in the Nyae Nyae Conservancy.

An elderly Herero man reportedly answered, “What will you have us do? Return to Gam to die?” The chief told him that they needed to obey the laws of their country, which do not allow them to move into Tsumkwe like that. “I as a San person respect that law. Why will you not respect that law?” he told him. According to Namibian law—the Traditional Authorities Act 25 of 2000, and the Communal Land Reform Act 5 of 2002—the traditional chief has the sole authority to determine the right to residency in the Nyae Nyae Conservancy.

The reporter didn’t mind using colorful prose: “Naked youngsters with the tell-tale signs of malnourishment—bulging stomachs and brown tinged hair—sit listlessly in a hut, while others cling to their mothers as they suckle milk.”

The reporter didn’t mind using colorful prose: “Naked youngsters with the tell-tale signs of malnourishment—bulging stomachs and brown tinged hair—sit listlessly in a hut, while others cling to their mothers as they suckle milk.” These families decided that things were getting too crowded in Wisconsin, where they came from, so they found farmland for sale to the west and decided to move. Most are not related to another new Amish community that has been established just over the state line to the south, in Nebraska. The new Nebraska Amish moved west from Michigan.

These families decided that things were getting too crowded in Wisconsin, where they came from, so they found farmland for sale to the west and decided to move. Most are not related to another new Amish community that has been established just over the state line to the south, in Nebraska. The new Nebraska Amish moved west from Michigan.