Kerala tries to include its citizens in decision-making as a way of strengthening local communities, but it has not succeeded as far as the Kadar are concerned. The Indian state’s Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) has made few attempts to integrate its plans for power generation with the culture of its indigenous communities, a recent research article concludes.

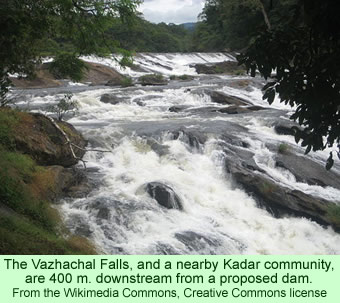

The article, by Tamara Nair, reviews the impact of the proposed Athirapilly hydropower project on two Kadar communities that are near the dam site. The project, initiated by the KSEB in the 1980s, was proposed to be constructed about 400 m. above the Vazhachal Falls on Kerala’s Chalakkudy River. The designers argued it would generate 163 megawatts of electric power.

Nair’s study area encompassed the two Kadar villages most closely affected by the proposed project. The author did her research for a period of five months, in 2010 and 2011, by conducting in-depth, semi-structured interviews among the Kadar and others in the immediate area affected by the proposed dam. She reviews the assessments made of the project and the claims by the Kadar that they were not informed that the assessment was being conducted. They only learned of the proposed project from accounts in the media.

The Kadar told her repeatedly that because they had not been consulted during the planning process for the dam, they felt as if they had been relegated to the fringes of society. They compared their recent treatment with their feelings of being ostracized, which they have felt since before the independence of India.

In Kerala, the policy of decentralization, the official reasoning goes, promotes sustainable development—local people are supposed to form cooperatives that prioritize projects. They become involved in planning processes and sometimes are included in the implementation of projects. State officials feel that this reduces corruption and helps alleviate poverty. However, the way the proposed hydropower project has been managed so far has only marginalized the Kadar, she concludes.

Nair found out during her interviews that the Kadar live up to their name: “people of the forest,” in the languages of that part of South India, Malayalam and Tamil. She learned that the Kadar senses are acute when they are in the wilds; they are expert at collecting honey and other non-timber forest resources, which they bring out to sell to the people of the plains. They have also been employed by several biologists and the managers of important conservation projects over the past decade. They have expert levels of indigenous knowledge, Nair argues, that can be important assets for development planning.

The author describes the two Kadar communities closest to the planned hydropower project. Vazhachal is less than 400 m. downstream and the other, Pokalapara, is about 4 km. upstream. The Kadar felt that government officials attached no importance to them, so their input about the dam was irrelevant. Nair characterized their attitudes as “mostly of apathy and hopelessness (p.402).”

She found that both men and women were resigned to the situation: no changes were likely. When they had to deal with authority figures or government officials, they had little if any confidence that anything positive would come of it. They felt that they were the last people to be considered by officials, and they seemed resigned to their position on the fringes of society. They were used to it.

A few of the author’s Kadar informants, however, expressed indignation at the treatment they had been given, and they desired more and better attention. But those Kadar were the ones who had gotten some education and belonged to social groups. They saw the dismissiveness of their opinions by officials as evidence of a basic attitude that they were primitive, or backward, and thus really unable to discuss development concerns intelligently.

Nair discovered that local elected officials and administrators were often aware of the problems that beset the Kadar communities. For instance, alcohol abuse, primarily caused by men who commute into towns for odd jobs and quickly spend their wages on alcohol, is a serious problem—a point which an earlier news story had mentioned. This alcohol issue came up when the author interviewed local officials, though they tended to blame the Kadar themselves for the problem.

However, the Kadar women Nair interviewed told her that they had informed officials repeatedly about it. They accused the local government of being quite aware that the easy availability of cheap alcohol was causing problems in their communities and of doing nothing to stop it. They even accused local officials of profiting from the illegal sale of alcohol, an accusation the author was unable to verify.

Opponents of the dam construction project generally side with the Kadar. Their displacement out of their forest homes and into the towns because of the dam could cause them to become further marginalized. This might force the state to address new problems if and when the Kadar were forced to try and integrate more fully into the mainstream society. The “knowledge and practices [of the Kadar] might be obliterated should they be compelled to assimilate,” Nair writes (p.406).

In addition to having an impact on the Kadar communities, the project might also harm the conservation of wildlife in the area, Nair has found. She suggests that compromising endemic fish species in the Chalakkudy River, plus riverine vegetation and several species of wildlife, is an issue with global implications.

Nair argues that while no one is actively trying to prevent the Kadar from participating in the planning process, no one is actively fostering their participation either. Development proposals move down from state agencies like the KSEB to local governments to local communities—but the Kadar are left out.

Legal recourse does exist for them. A woman in the Vazhachal colony launched what is called a Public Interest Litigation in the Kerala High Court because her colony appeared to be removed from a map that demarcated the area of impact from the proposed dam. This same woman has registered complaints with various officials on other occasions about the sale of alcohol. Nair concludes, however, that these developments are matters of survival and struggle for the Kadar rather than, what they should be, issues of involvement and active participation.

Nair, Tamara. 2014. “Decentralization and the Cultural Politics of Natural Resource Management in Kerala, India.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 35(3): 397-411