The Ladakhis went to the polls last Wednesday, one of the last regions of India to vote in the lengthy process of electing a new parliament.

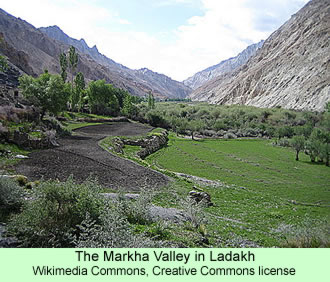

But unlike many areas of the country, providing polling booths and ballots to some of the rugged mountain communities proved to be a challenge. In Anlaythu, at 15,000 feet above sea level, 57 people were expected to vote. The government used helicopters to transport the voting booths to the community. Many other mountain communities, such as Rumbag and the Markha Valley, are just as remote, being accessible only through arduous treks, and they too needed voting booths and election officials.

But unlike many areas of the country, providing polling booths and ballots to some of the rugged mountain communities proved to be a challenge. In Anlaythu, at 15,000 feet above sea level, 57 people were expected to vote. The government used helicopters to transport the voting booths to the community. Many other mountain communities, such as Rumbag and the Markha Valley, are just as remote, being accessible only through arduous treks, and they too needed voting booths and election officials.

Simranjit Singh, Leh deputy commissioner, indicated to a journalist that one remote village, Lingsshet, has 400 voters, but the average for the rest of them is about 60. He said that places like Anlaythu and Dumchuk, with 80 voters, are so close to the border with China that the Chinese will “get to see [the] live Indian democratic process.”

The weather in Ladakh last Wednesday was good, fortunately, encouraging a turnout according to one news story of 65 percent, and 63 percent according to another.

Aljazeera provided an interesting, in-depth analysis on Wednesday of the voting process in Ladakh. The journalist who wrote that story also quoted Mr. Singh on the difficulties—and expenses—of getting the Ladakhis to the polls: one lakh rupees (U.S.$1,667) per voter. The reporter indicated that voting was peaceful, a contrast to some reports of strife in other parts of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, of which Ladakh is a part.

One of the biggest difficulties for the election officials was maintaining the health of the poll workers, some of whom had problems becoming properly acclimatized to the high altitudes of Ladakh. Singh expressed concern about their health and their safe return, since snows in the mountain passes could still block roads and trails.

The Aljazeera journalist spoke with Ramesh Kumar Bhat, a polling officer who hiked for two days to the hamlet of Fastan, located at 12,000 feet. He evidently was exhausted by the climb, crawled on his belly, gasped for air. The group of four, including a police escort, had pills to take to help against the altitude sickness. They had a couple ponies to transport their food, sleeping bags, and, most critically, the electronic voting machines.

Bhat didn’t mind dramatizing his adventure for the reporter. “It was a spectacular view but I did not dare take a photo because the path was so treacherous and we were worn out,” he said. He added, “I was very scared and I prayed a lot. My stomach was bloated, eyes were burning, nose bleeding and I had a thumping headache.” The effort was evidently worth it, however, since 24 out of the 26 registered voters in Fastan actually turned out to vote.