Mark Sicoli is using a path-breaking linguistics analysis technique to better understand the ways that gestures and behaviors used by speakers of a Zapotec language affect their speech. He and a team of student assistants at Georgetown University are examining 40 hours of videos of people speaking Lachixio, one of the Zapotec languages, as they socialize, interact with visitors, or just eat dinner. In essence, the team members are analyzing the social contexts of speech in Zapotec villages.

“These are not setups,” Professor Sicoli says in an article published about his work last week. “This is just what people would be doing if they were just going about their normal stuff. Through all this work, we get the flavor of the language—not just the words and rules but also the flavor of how it gets used in social life—which are, in a sense, another level of rules for the use of language.” Sicoli is a professor of linguistics at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

“These are not setups,” Professor Sicoli says in an article published about his work last week. “This is just what people would be doing if they were just going about their normal stuff. Through all this work, we get the flavor of the language—not just the words and rules but also the flavor of how it gets used in social life—which are, in a sense, another level of rules for the use of language.” Sicoli is a professor of linguistics at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

The Linguistic Society of America considers Lachixio to be an endangered language. It is spoken by about 3,000 speakers, concentrated in four towns in the state of Oaxaca in southern Mexico. Prof. Sicoli’s group, named the Multimodal Interaction in Meso-America, is analyzing the videos, dating from the summers of 2008 and 2009, to determine the ways the language, gestures, and other behavior patterns interact in everyday usage. This is referred to as multimodal analysis, and it is based on the theory that language is broader than just speech.

Prof. Sicoli was introduced to Lachixio while working on a masters degree project in that part of Mexico. He then learned the language. “I found the people fascinating and the languages very fascinating to me,” he said. He explained to the reporter from The Hoya, the Georgetown University student newspaper, that the rising importance of spoken Spanish is symbolic to the Mexican people of their nationalism, but this threatens the continuing importance of local languages.

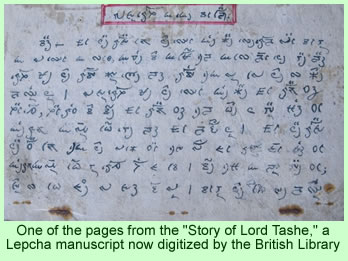

Sicoli’s work is part of the Documenting Endangered Languages Program, an archive of 2,500 phrases spoken in the 103 towns where people speak one of the Zapotec-Chatino languages. Lachixio is one of about 26 languages in that language family. But documenting the languages “doesn’t capture language in its natural ecology,” Sicoli contends.

Researchers have focused on documenting words and phrases, he says, but “looking at language in use and how people are using that to coordinate their activities in everyday life has been mostly absent, but it’s a growing area. It’s a cutting-edge area of linguistics,” he argues. His work is supported, and encouraged, by both the U.S. National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Science Foundation.

“This is really the future of documentation—how language is used to do all of the things that we do as people—because it’s such a part of everything we do,” the professor says. But he emphasizes that he does not think he is saving the language. That is really up to the people in the Zapotec communities. He trains native Zapotec speakers to do linguistics work and develop their own teaching materials. He hopes his work will help facilitate their own efforts to use and maintain their languages—which will presumably strengthen their cultures.