At a public meeting last Wednesday in the Nellore District of Andhra Pradesh, state legislators alleged that the Yanadi suffer from abject poverty due, in part, to the negligence of government officials.

Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLA), the lower house of the state legislature, and members of the Legislative Council, the upper house, criticized the agency of the district government charged with administering rural areas of Nellore. The legislators argued that the agency, called the Zilla Parishad, had failed to improve Yanadi health and welfare.

The legislators, according to a news report last week, were especially critical of the Integrated Tribal Development Agency (IDTA) and its Project Officer, K. Ramesh, who had not adequately informed the representatives about agency activities and had not generated proper publicity about its welfare programs.

The Nellore District IDTA is responsible for three additional districts in addition to Nellore. Out of the 550,000 tribal people who live in the four districts, 379,000 are Yanadis.

Beeda Masan Rao, a Member of the Legislative Assembly, indicated he resented the ITDA Project Officer not inviting legislators and other appropriate officials to meetings. He argued that better communication might allow legislators to alert administrators about local problems, and he blamed underdevelopment on the official negligence.

Representatives to the Zilla Parishad complained that tribal students lack adequate classrooms, kitchens, and toilets in the schools run by the district. Some schools are quite dilapidated and need to be replaced.

The chairman of the Zilla Parishad, Kakani Goverdhan Reddy, responding to the complaints, directed the Project Officer of the ITDA to invite legislators in the future to government body meetings and to provide adequate information to them ahead of time. The news story does not indicate if anyone is going to investigate the inadequate schools, much less other causes of their poverty.

According to a story in the

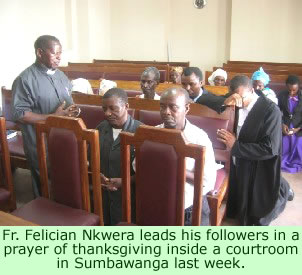

According to a story in the  The story goes back to a young priest named Felician Venant Nkwera, who came from the Iringa Region of southwestern Tanzania, near Lake Malawi, south of the traditional Fipa territory. Born in 1936, he entered the priesthood in 1968 in a southern town, but was soon assigned to Madunda Parish, in northern Tanzania. He baptized a sick infant, who had almost been pronounced dead, and when he poured water on the infant, the child miraculously seemed to be restored to full health.

The story goes back to a young priest named Felician Venant Nkwera, who came from the Iringa Region of southwestern Tanzania, near Lake Malawi, south of the traditional Fipa territory. Born in 1936, he entered the priesthood in 1968 in a southern town, but was soon assigned to Madunda Parish, in northern Tanzania. He baptized a sick infant, who had almost been pronounced dead, and when he poured water on the infant, the child miraculously seemed to be restored to full health.

The idea of such a reconstruction floated around for years in Gangtok, the capital of Sikkim. A foundation stone had been laid by the Chief Minister for the state in 1995, but the project got nowhere due to a lack of funds. The estimated cost—Rs 300 crore ($US 63,700,000)—was much too high. In August 2009, the Roads and Bridges minister, R.B. Subba,

The idea of such a reconstruction floated around for years in Gangtok, the capital of Sikkim. A foundation stone had been laid by the Chief Minister for the state in 1995, but the project got nowhere due to a lack of funds. The estimated cost—Rs 300 crore ($US 63,700,000)—was much too high. In August 2009, the Roads and Bridges minister, R.B. Subba,