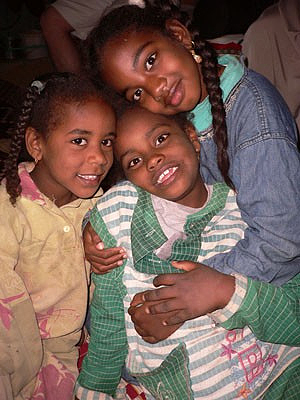

A news website called The Malaysian Insight published a photo story last week about the Chewong mahouts who work with the elephants at the Kuala Gandah National Elephant Centre.

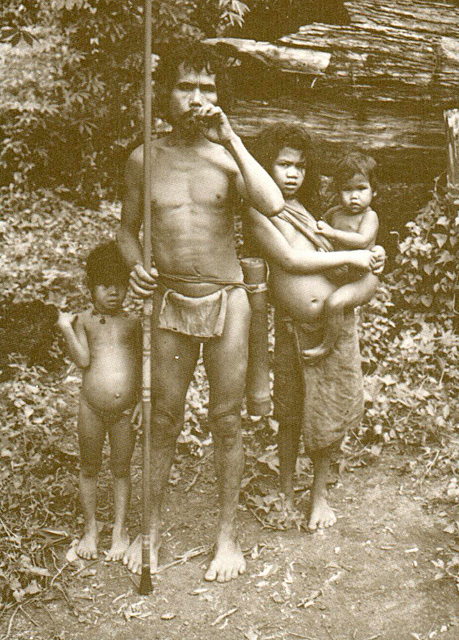

The brief text that accompanies the 10 photos indicates that for 10 years, the Chewong have been trained as elephant keepers and mahouts at Kuala Gandah, located in Malaysia’s Pahang state. The training program there teaches the Chewong how to care for elephants and it gives the employees additional, useful skills. The training program also gives the Department of Wildlife and National Parks insights into working with the Orang Asli people.

Kuala Gandah currently has 25 elephants, some of which the author, Seth Akmal, photographed with their Chewong handlers. The ten photos that accompany the brief story include a Chewong mahout bathing an elephant, mahouts riding their elephants before a show, mahouts bringing their animals close to visitors, and so on.

According to Howell (2015), the National Elephant Conservation Centre was developed by Malaysia in the late 1980s right next to the village that the government had established for the Chewong at the edge of the Krau Game Reserve. The village was designed in an effort to get them to accept a settled, agricultural lifestyle. Elephants were then brought to Kuala Gandah from all over Malaysia as the natural forests of the country were cleared, mostly for palm oil plantations.

Kuala Gandah is widely promoted as a major tourist attraction—as of 2009, Howell wrote, it hosted 150,000 visitors and the numbers were increasing. A paved road leads into the area, ending at the boundary of the Krau Game Reserve where the Chewong have traditionally hunted, fished, and gathered. At the end of the road, the pavement divides, the right fork leading into the elephants, the left into the “aboriginal reserve,” according to a sign.

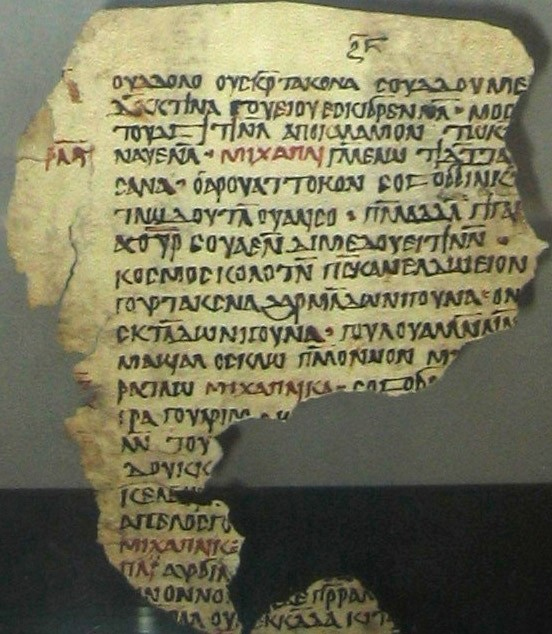

In the early period of the elephant sanctuary, it did not employ any Chewong but as of the date of Howell’s most recent visit, several Chewong men, but no women, were employed as guards or cleaning workers. The government erected a small building as an exhibit space for the sale of Chewong crafts to visitors and as a place for them to sit and listen to lectures about the Orang Asli people, their beliefs and practices.

Howell wrote that she attended the public lectures several times, listening to presentations by a woman that were filled with inaccuracies. The same woman, the wife of another employee, also managed the shop where the Chewong crafts are sold. According to rumors, the Chewong only receive a small portion of the proceeds but, “true to form, no Chewong confronts her about this (p.70).”

Howell (2015) concluded that she has observed many changes in Chewong society over the decades that she has been doing fieldwork among them. Most of the changes are due to pressures from the surrounding, larger society. But she doubts that the Chewong will necessarily end up as badly as many other former hunter-gatherer societies have been doing. They may not become stricken with poverty as others have because of the modernization that surrounds them. In essence, she feels that they may be able to avoid that fate.

The Chewong are motivated by numerous different beliefs and local influences that will prompt them to make a variety of choices. Howell found it difficult to predict how well they will react to each new constraint, but presuming her article is an accurate guide, it is clear that they will make their own best choices for themselves. Ten of their men have chosen to accept employment as mahouts—but others may choose to go into the forest and forage for their food. It will be their choice.