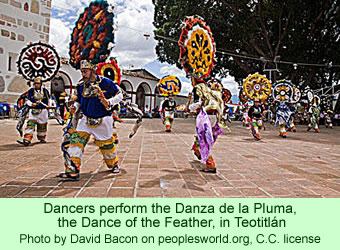

David Bacon considers the Zapotec “Dance of the Feather” to be “one of the world’s most beautiful dances.” In an article republished last week from his earlier piece in the publication Contexts from the American Sociological Association, Bacon argues that the unique dance represents the history and culture of the Zapotec of Oaxaca’s Central Valley.

The Dance of the Feather is performed in numerous towns, most notably in Teotitlán del Valle, a community that is celebrated for its many weaving establishments. The dance represents, in part, the defeat of Moctezuma by Cortes. The author quotes extensively from an anthropologist in Oaxaca, Jorge Hernandez Diaz, who describes three different theories as to the origin of the dance.

The Dance of the Feather is performed in numerous towns, most notably in Teotitlán del Valle, a community that is celebrated for its many weaving establishments. The dance represents, in part, the defeat of Moctezuma by Cortes. The author quotes extensively from an anthropologist in Oaxaca, Jorge Hernandez Diaz, who describes three different theories as to the origin of the dance.

One was that it was first developed by Martin, the illegitimate son of Cortes by the native woman Malinalli (also known as Doña Marina or Malinche) who was his mistress. Martin became a wealthy landlord in the Valley of Oaxaca after the death of his father. The legend goes that Martin invented the dance to dramatize the Spanish conquest of the indigenous people of Mexico. The dancers represent Cortes, Moctezuma, and their respective allies. The dancers today perform the same characters, though with different meanings.

Other versions of the history of the dance exist. In one, the dance was performed before the conquest. The dancers represented various characters in preexisting, warring kingdoms. Hernandez, the anthropologist, also describes a possible symbolic, astronomical, role for the dance, with Moctezuma representing the sun and the other dancers, the planets.

Whatever the history of the dance may have been, it now has considerable impact in Teotitlán; it is an important part of the fiesta celebrated in the town. Hernandez explains, “it is a tradition that can’t be overlooked, given that it’s part of [the] cultural, ceremonial and spiritual identity [of the community].”

Bacon continues that while the intention of Martin, the son of the conquistador, in initiating the Dance of the Feather may have been to justify Spanish rule and to dramatize to the indigenous people that resistance was futile, today it has assumed very different meanings. It now represents a spirit of Zapotec resistance to anything that would try to take away their dance, language, music, or traditional culture.

It is an important element in the Zapotec maintenance of their cultural values, despite the centuries of colonization and national policies that have sought to minimize their identity. The dance is important in communities that treasure their traditions, such as Teotitlán. It reaffirms what the people believe to be a glorious past—before the arrival of the Spanish—and it prevents forgetting their traditions by the way it celebrates the struggle to maintain the native Zapotec beliefs.

In Teotitlán in particular, the dance also celebrates the renewal of the town as a center of the weaving industry. Fifty years ago, it had become quite poor, its weaving craft fading as many residents had left. But remittances sent back by those employed in urban areas of Mexico and the U.S. helped provide materials to revive the weaving business. An influx of tourists looking for carpets filled with traditional Zapotec designs also helped revive the community.

Hernandez indicates that, for Teotitlán, the Dance of the Feather is “a strategy for defense against what they felt were negative influences of the modern world, against the consequences of migration, against the loss of moral values and customs.” He says that the dance has had its ups and downs in the town, at times not being performed, breaking the ancient traditions, but then later it’s been revived—and modified.

Although the photo above gives an impression of the Dance of the Feather, a 12-minute YouTube video of a performance in Teotitlán in 2014 is even better. While the video does not include any commentary, the wonderful costumes and headdresses of the dancers—all men—and their intricate, highly athletic, dance steps are shown in detail. When readers of Bacon’s essay watch the video, they might want to try and spot the historical and cultural aspects that he describes.

He provides careful background in

He provides careful background in

Mr. Harikishore has been able to find the funding to ensure that the children attending the school are given three meals every day, one of the major issues reported last month. Another problem was that promises to provide daily transportation service to and from the school to the other nearby Malapandaram communities in the forest areas of Chalakkayam, Nilackal, and Laha had not been fulfilled.

Mr. Harikishore has been able to find the funding to ensure that the children attending the school are given three meals every day, one of the major issues reported last month. Another problem was that promises to provide daily transportation service to and from the school to the other nearby Malapandaram communities in the forest areas of Chalakkayam, Nilackal, and Laha had not been fulfilled.