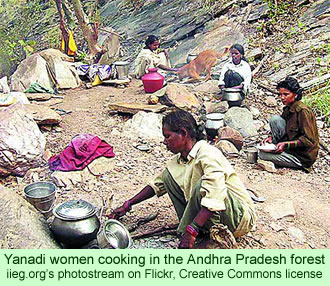

Some very poor Yanadi families in India’s Andhra Pradesh state seem to be getting more welfare support, but others are losing out due to official corruption. Two articles last week in The Hindu, a major paper in India, provided details about the situation.

An article on Thursday, the more hopeful one, indicated that over 10,000 Yanadi families in the Nellore District of the state were going to be receiving much more generous ration allotments, called Antyodaya cards, which will allow the recipients to receive 35 kg. of rice per family per month. Those amounts are not varied depending on the sizes of the families.

An article on Thursday, the more hopeful one, indicated that over 10,000 Yanadi families in the Nellore District of the state were going to be receiving much more generous ration allotments, called Antyodaya cards, which will allow the recipients to receive 35 kg. of rice per family per month. Those amounts are not varied depending on the sizes of the families.

Apparently, officials in the district led by District Collector B. Sridhar carefully studied the very poor living conditions of the Yanadis and came to the conclusion that a large number of them needed additional assistance. They tend to subsist on rice and the fish that they catch in canals and roadside ponds. They eat the fish with their rice and sell the excess for income.

An earlier ration card that allows only 4 kg. of rice was clearly inadequate, so they were forced to buy rice from others at a cost of Rs. 10 per kg, money which was difficult for them to raise. Mr. Sridhar said, “more rice allotment is going to be a big relief for them. The Antyodaya ration will be given to them from March 1.”

Out of nearly 84,000 people classified as members of Scheduled Tribes in the Nellore District, about 65,000 are Yanadis. A project officer for the Integrated Tribal Development Agency (IDTA), Y. Venkateswarlu, was quoted as saying, “a little change is being seen now.”

That same day, last Thursday, The Hindu carried another story by a different journalist from another area in Andhra Pradesh, the West Godavari District, where the news about relief for the Yanadi was not as positive. A group of tribal peoples, including Yanadi, demonstrated outside the local offices of the IDTA, protesting corruption in the agency that prevented them from receiving the benefits that had been allocated to them.

Sodim Venkateswara Rao, a representative from Girijana Samakhya, a tribal support organization, said that welfare funds were not reaching the people. They were being skimmed off by people in the ITDA. Despite large amounts of money being allocated by the government to help the living conditions of the Yanadi and the other tribal peoples, their conditions, at least in that district, have not changed due to the corruption.

D. Prabhakar, the local District Secretary of the Communist Party of India (CPI), pointed to the recent suspension of two ITDA officers due to charges of graft as an indication of the high levels of corruption in the agency. This situation has a severe impact on the tribal people. Corruption helps prevent appropriate health care, road networks, and mobile health units being provided for the Yanadi, Prabhakar alleged.

A spokesperson from the Yanadi community in the district, Ravuri Syambabu, said that the ITDA was not extending the proper welfare assistance to his community. He argued that out of the 200 people from 30 families living in one Yanadi colony, Balusumudi, only five to ten were able to write their names, and only one child, a girl, had studied up to the intermediate level of schooling. Poor literacy is a hallmark of the Yanadi people in the district, he complained.

Other recent news stories have similarly focused on corruption in Andhra Pradesh and its effect on the Yanadi. One, in March 2010 reviewed how corruption was affecting the construction of new housing for Yanadi families in the Nellore District. Another, in July 2010, described corruption by the IDTA office in the same district and its affect on the Yanadi people.