The government of Egypt decided last Wednesday that the Nubians who had been forced out of their homes in 1902 by the construction of the first dam at Aswan were to have legal title to their replacement properties. The construction of the so-called Aswan Low Dam flooded out many Nubians, though not nearly so many as the High Dam did in 1964.

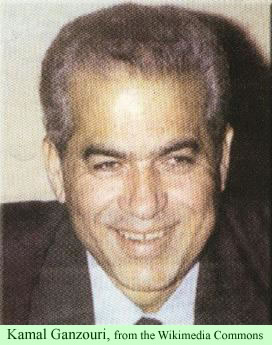

The cabinet of Prime Minister Kamal al-Ganzouri decided that the parcels of land on which generations of Nubians had been living since 1902 should now be officially deeded to the people living there. The properties range in size from 350 to 1,000 square meters.

The cabinet of Prime Minister Kamal al-Ganzouri decided that the parcels of land on which generations of Nubians had been living since 1902 should now be officially deeded to the people living there. The properties range in size from 350 to 1,000 square meters.

Ganzouri had served under President Hosni Mubarak as Prime Minister from 1996 to 1999 before he was dismissed. Last fall, after Essam Sharaf resigned as Prime Minister, the real rulers of Egypt, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, appointed Ganzouri as Prime Minister. He has control over all government affairs except for the military and the judiciary.

Ever since Mubarak was toppled from power in January 2011, the Nubians have been agitating for the right to return to the lands near Lake Nasser, formerly the River Nile, to which they have a strong cultural attachment. In September, Nubian protesters in Aswan set fire to the government building during their demonstrations. They staged a sit-in the office of the Aswan Governor, in protest against government policies of the former prime minister, which were seen as mostly empty promises that did not allow them to return to the banks of the lake.

As a result of their protests, the current Prime Minister met with Nubian representatives and agreed to this latest decision in their favor.