The two Ladakhi districts have passed separate resolutions demanding that the state of Jammu and Kashmir create a separate division for them. A news story in the Indian Express on December 8 indicated that feelings are strong throughout Ladakh for the proposed separation.

On December 1, the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council, Leh, unanimously passed a resolution demanding the separation; a comparable body, the LAHDC, Kargil, passed a similar resolution on December 6. On Friday December 7, Jamyang Tsering Namgial, the Chief Executive Councilor of the LAHDC, Leh, emphasized to the news service that his organization is demanding “complete administrative autonomy from Kashmir.”

He went on to argue that they are demanding separate status because Ladakh has been neglected repeatedly by the state government. Furthermore, it is basically an impossible administrative arrangement—Leh is 400 kilometers from Srinagar, the summer capital of the state. Namgial further maintained that the state has three distinct regions—Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh, but “Ladakh has to constantly fight for resources from Kashmir.”

He pointed out that the central government of India last year approved Rs 50 crore (almost U.S. $7,000,000) for pashmina development, but Ladakh has not as yet seen any of that funding. The LAHDC, Leh, also passed a resolution condemning what it termed as the backwardness of the district in terms of development and education. “The problems of the region have never been addressed,” according to that resolution.

Members of the two councils had separate meetings with the governor of the State, Satya Pal Malik and some of his staff in the city of Jammu to press their demands.

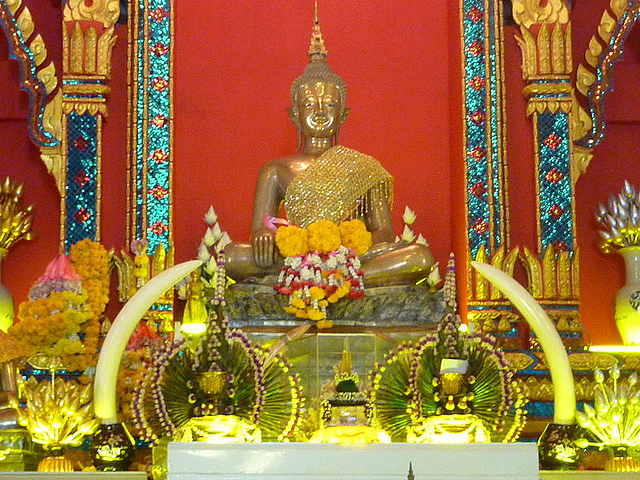

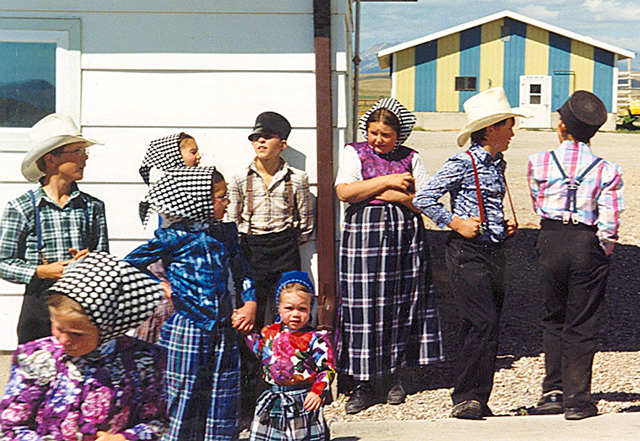

The article in the Indian Express does not mention a fact that would be well known to readers in India—that the two different districts of Ladakh, Leh and Kargil, have very distinct cultures and recent histories. To simplify, the people of Leh are primarily Tibetan Buddhists with a minority of Muslim residents, while the Kargil District is primarily Muslim with a minority of Buddhists. It appears as if they are united in terms of having strained relations with the state.