Although olive ridley sea turtles are still fairly common globally, they are considered to be threatened because they have few secure nesting sites left in the world.

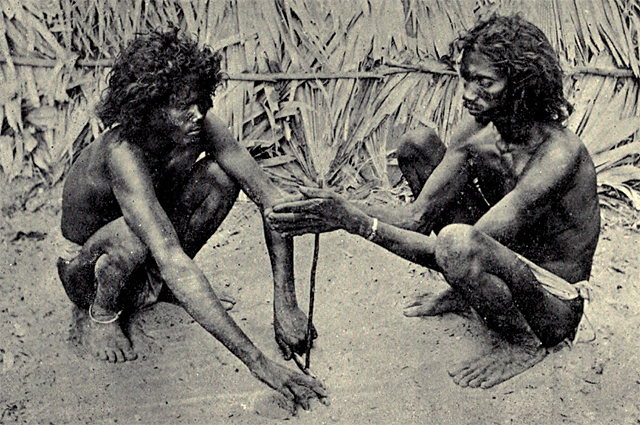

At one of the nesting areas, the beaches of the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh along the Bay of Bengal, Yanadi fishermen have taken a strong interest in helping protect the turtles. A news report in The Hindu last week explained the conservation program and the role of the Yanadi people.

On Tuesday, April 25, a government conservation official, Mr. Ramana Reddy, released almost 800 turtle hatchlings into the sea near the Edurumondi Lighthouse in the Krishna District of the state. So far this year, he told the reporter, T. Appala Naidu, over 33,000 turtle hatchlings have been released into the bay along the state’s coastline. “All … efforts are being made to intensify conservation of the olive ridley turtles,” he said.

The importance of releasing sea turtles into numerous sites along the coast is that when they are grown into adults, they will return to the same beaches where they entered the sea to lay their own eggs. The propagation efforts will help reestablish the former abundance of the turtles. In return for the persistent work of government forestry officials and their volunteer helpers, about 824 adult turtles have returned to the beaches of the Krishna and Guntur districts of the state to make their own nests. In order to assist in propagating the species, over 93,000 eggs have been taken from the turtle nests, from which the hatchlings have been successfully released into the sea.

Mr. Reddy paid tribute to the Yanadi volunteers who participated this year in helping collect and protect eggs from the beach nests. They deserve a lot of credit, Mr. Naidu wrote, for the conservation of the turtles, particularly in the Krishna District. A team of Yanadi families has worked at the rookeries as part of their assistance to the project.

A news story in early May last year described the lives of the fishing Yanadi families living in the coastal beach areas of Andhra Pradesh. The same reporter, Mr. Naidu, interviewed some of them and they made it clear how comfortable they felt about living next to the sea. They were glad to be involved with collecting the turtle eggs and helping release the hatchlings.