A sit-down strike begun in April by 46 Lepcha paraprofessional teachers protesting their treatment by Gorkha authorities in India’s West Bengal State ended peacefully last week when a face-saving compromise was announced. The strike by the teachers, called a dharna in India, had been in effect for 109 days. They were pleased to receive a letter from the West Bengal Education Department that assured them an interim arrangement for their employment had been devised.

The conflict was an important news story back in April and early May in the Indian media. The basic issue was that the Lepchas wished to have their children receive instruction in their own Lepcha language in the public schools. Officials in the state government agreed and appointed 46 people, para-professional teachers, to teach Lepcha in the 46 schools of the Darjeeling District of West Bengal.

The conflict was an important news story back in April and early May in the Indian media. The basic issue was that the Lepchas wished to have their children receive instruction in their own Lepcha language in the public schools. Officials in the state government agreed and appointed 46 people, para-professional teachers, to teach Lepcha in the 46 schools of the Darjeeling District of West Bengal.

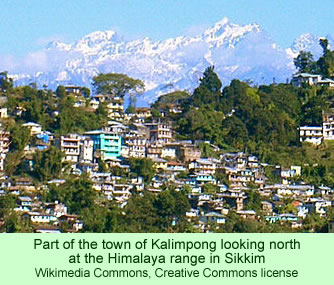

The Gorkhaland Territorial Administration objected, claiming it alone had the authority to hire teachers. After a series of maneuvers with various administrators and the courts, the newly-appointed teachers launched their strike in the town of Kalimpong to dramatize their treatment at the hands of the GTA, a group with administrative powers with whom they have had rocky relations for years.

The news last week was positive—a compromise that will allow the 27 men and 19 women to start teaching Lepcha to the children. The letter from Mr. A. Roy, the West Bengal State School Education Department Secretary, told the teachers that the education ministry had arranged for them to teach in the Lepcha medium schools, organized under the auspices of the Mayel Lyang Lepcha Development Board (MYLDB), which was formed in 2013.

Peter Lepcha, one the 46 teachers, commented, “The State government has resolved our issue in a wise manner and our dharna did not go in vain. Our problem of unemployment has been addressed and now we can earn our livelihood.” According to another news report carried by Facebook, Mr. Lepcha added, “this is a victory of our agitation, and even though schools under MYLDB might be unrecognized, at least we are happy that there will be some reduction in unemployment in the hills.”

A petition from the GTA is still pending in the courts, so until that is resolved, the paraprofessional teachers will be teaching in non-recognized medium schools and night schools that the Lepcha board administers, rather than in the regular schools. They will be paid salaries from the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, a movement aimed at promoting universal elementary education administered by the government of India. The state department of education has approved this arrangement, according to the letter.

Several officials from the All India Trinamool Congress (TMC), the ruling political party of West Bengal state, expressed pleasure at the compromise resolution. Bhupendra Lepcha, the district youth president for TMC, said that the future of the 46 teachers was now secure, and Chawang Bhutia, the TMC Hill secretary, congratulated state officials for effectively resolving the situation. He thanked the teachers for being patient.

She and her family have spent three months on Mann and they are nearing the time when they will be returning to Tristan. A reporter for a

She and her family have spent three months on Mann and they are nearing the time when they will be returning to Tristan. A reporter for a

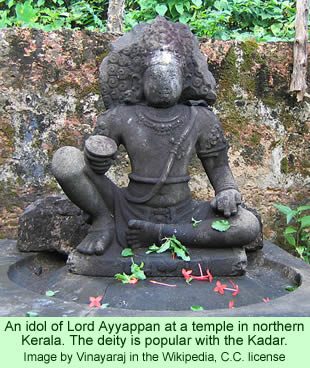

The local Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA), Raju Abraham, joined the festivities in opening the new school. Attathode is the second largest tribal settlement in Kerala. Children from some of the other Malapandaram settlements along the road from the district administrative center, Pathanamthitta town, to Sabarimala attended the opening. The huge temple complex of the prominent god Lord Ayyappan is located in Sabarimala.

The local Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA), Raju Abraham, joined the festivities in opening the new school. Attathode is the second largest tribal settlement in Kerala. Children from some of the other Malapandaram settlements along the road from the district administrative center, Pathanamthitta town, to Sabarimala attended the opening. The huge temple complex of the prominent god Lord Ayyappan is located in Sabarimala.