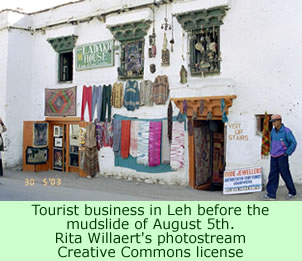

The peaceful Ladakhi culture will certainly survive the winter, but many inhabitants of Leh and vicinity are facing a very difficult time ahead due to the tragic mudslide of August 6th. Freak cloudbursts the night of August 5th caused a huge mudslide to devastate the city very early the following morning. The news media in India are carrying reports of fund raising efforts, personal stories of the tragedy, and problems with replacing houses before cold weather arrives.

Fund raising and charitable giving in India to benefit the victims appear to be developing quite well. Thirty five Indian photographers donated their works for a benefit sale, held the weekend of September 3 – 5 in New Delhi. Called “ SOS Ladakh,” the exhibition included photos of such things as colorful monks framed against backdrops of stunning Ladakhi natural scenery. In addition to breathtaking views, the photos depicted scenes of human suffering and difficult terrain.

The exhibition included numerous popular Indian photographers, and various media personalities attended. It raised Rs. 20 lakh (U.S.$43,000) for the relief efforts.

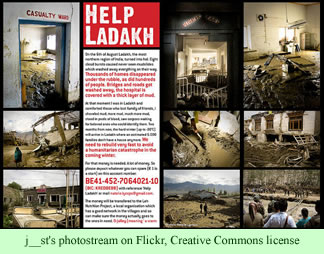

In addition to the displays of photos, the exhibition included souvenirs, accessories, and posters related to the tragedy. A “Help Ladakh” poster depicted on Flickr includes 9 separate photos, including several of buildings filled with and destroyed by the mudslides. The poignant picture in the upper left corner of the poster shows a room in a hospital labeled “Casualty Ward,” which is, itself, a casualty of the mudslide.

In addition to the displays of photos, the exhibition included souvenirs, accessories, and posters related to the tragedy. A “Help Ladakh” poster depicted on Flickr includes 9 separate photos, including several of buildings filled with and destroyed by the mudslides. The poignant picture in the upper left corner of the poster shows a room in a hospital labeled “Casualty Ward,” which is, itself, a casualty of the mudslide.

The Tribune of India reported on Friday that its relief drive has so far raised Rs 1.5 crore (U.S.$3.2 million) for relief. All of the money, according to the paper, is going to the Prime Minister’s National Relief Fund. The Editor-in-Chief of the Tribune concludes his editorial by expressing his gratitude to the readers of the paper for their magnanimity in helping the affected citizens of Leh.

But not all reports about the relief efforts are positive. A story on Saturday indicated that a prominent actor named Rahul Bose, who serves as ambassador for Oxfam India, traveled to Leh along with the director of the agency, Nisha Agarwal, and their comments were ominous. While Ms. Agarwal described the water and sanitation facilities that Oxfam is providing, delays seem to be holding up the construction of new houses to replace the several thousand homes that were heavily impacted or destroyed in the mudslide.

Ms. Agarwal commented that the government, which is responsible for building the new houses, has only a month or so of remaining good weather to erect more permanent facilities in order to protect the people who are still living in temporary tent communities.

Another report on Saturday was even more direct. Many of the victims of the mudslide now appear to be resigned to spending the winter in tents. The largest refugee complex, called the “Solar” camp, houses 230 families in 50 some tents about six km from Leh. The Times of India described the delay in building better housing for the victims as a serious problem. “Living in tents for month[s] while everyone gets their act together, is not a solution. They have to move into more sheltered and secure lodgings and soon.”

Apparently not a single house has yet been built, and the resignation of the tent dwellers seems inevitable. The government needs to bring 900 metric tons of steel, 1,400 metric tons of cement, and 604 tons of pipes, among other massive amounts of supplies, into Leh very rapidly in order to do the construction work. About 2,000 trucks will be needed to haul the supplies over the mountains, and the transportation situation is difficult due to the fact that only two highways lead to Ladakh. One of them, the Manali to Leh road, is closed at the moment, and the Srinagar to Leh highway is unable to carry the weight of large trucks.

Bureaucratic hassles also bedevil the construction efforts. The government has provided money for rebuilding, but it is being made available through the State Bank of India—in stages. However, nearly a third of the legitimate claimants lack accounts, which apparently hampers their access to the funds.

The press reports also include accounts of what people have been actually experiencing, and the losses they have suffered. Stanzin Dolkar, a 27 year old woman, lost three of her cousins in the tragedy, two of whom are still missing, and the body of the third was only found a few days ago. “It wouldn’t be easy to get over the tragedy,” she said. “I rushed to help my neighbours and even pulled three of them out from the collapsed houses. The water damaged my house as well, but the houses that were across the road were washed away.”

At the Solar camp, children are going back to school, but they find it difficult to concentrate due to the situation. Padma Chuskit watched from a neighbor’s house as her own home was swept up by the mudslide.

The farmers around Leh have found their fields filled with boulders, their soil washed away, their tools, equipment, and supplies lost. Many irrigation channels, vital to Ladakhi agriculture, were destroyed, though most farm animals, fortunately, survived. The Ladakhi people will rebuild, and doubtless will benefit from the assistance of many generous supporters—and even, at some point, from the government bureaucracy. The peaceful paradise, as many people romanticize Ladakh, will again become a tourist destination, some day.

One of the major problems for the Mbuti refugees outside Goma, at the eastern edge of the country, is that much of the land is covered with lava from a volcanic eruption in 2002 and is completely unsuitable for agriculture. Mupepa Muhindo, an Mbuti representative from the refugee camp Hewa Bora who was also quoted in the May report, told IRIN that it was not possible to cultivate the soil.

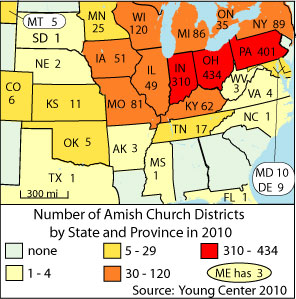

One of the major problems for the Mbuti refugees outside Goma, at the eastern edge of the country, is that much of the land is covered with lava from a volcanic eruption in 2002 and is completely unsuitable for agriculture. Mupepa Muhindo, an Mbuti representative from the refugee camp Hewa Bora who was also quoted in the May report, told IRIN that it was not possible to cultivate the soil. His basic argument is that other societies can provide useful mirrors so we can reflect on our own ways of doing things. This is particularly true of societies that do not fight wars with neighboring peoples. He calls them “peace systems.” He cites seven peace systems from the literature and carefully describes three.

His basic argument is that other societies can provide useful mirrors so we can reflect on our own ways of doing things. This is particularly true of societies that do not fight wars with neighboring peoples. He calls them “peace systems.” He cites seven peace systems from the literature and carefully describes three.

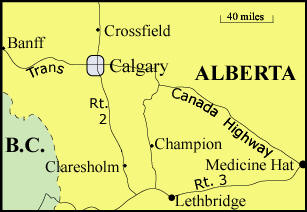

The colony owned about 1,000 hectares of land (2500 acres), which is not enough to allow sufficient agricultural production for a growing population. The Hutterites were unable to buy additional property since they were too close to the expanding metropolitan region. They searched for, and found, a 5,260 hectare (13,000 acres) tract in the prairie two hours south of Calgary, between Champion and Claresholm, two-thirds of the way to Lethbridge, Alberta.

The colony owned about 1,000 hectares of land (2500 acres), which is not enough to allow sufficient agricultural production for a growing population. The Hutterites were unable to buy additional property since they were too close to the expanding metropolitan region. They searched for, and found, a 5,260 hectare (13,000 acres) tract in the prairie two hours south of Calgary, between Champion and Claresholm, two-thirds of the way to Lethbridge, Alberta.