For some of the peaceful societies, glimpses of their traditions can be gleaned from histories of the Europeans who invaded their lands and who subsequently chronicled their own accomplishments. A good case in point would be the Tahitians, whose many customs were richly noted by the 18th century French and English visitors. While stories of lusty Tahitian maidens climbing aboard tall ships for their pleasures with the sailors titillated the European imaginations of the time, most of the visitors came for serious purposes and, to some extent, they recorded interesting details about Tahitian life.

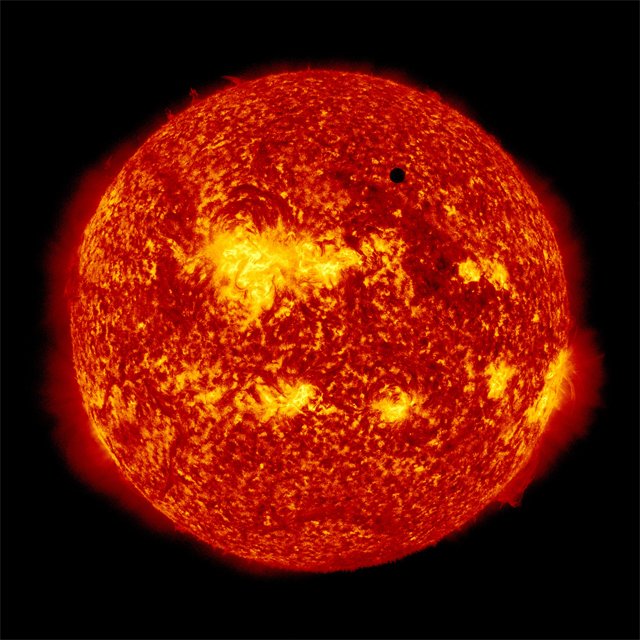

An article published last week in the Otago Daily Times from Dunedin, New Zealand, focused on the scientific aspects of Captain James Cook’s visit to Tahiti in 1769 and the observations by contemporary scientists in the ship of the transit of Venus across the face of the sun. Cook’s voyage to Tahiti and other places in the Pacific was part of a worldwide effort to track the transit by scientists and trained observers.

The author of the article, Neville Peat, visited Tahiti and made a point of celebrating the 250th anniversary of Cook’s astronomical observations by visiting the wooded area along the north coast of the island, called Point Venus. It was so named by Cook and the name has stuck to this day.

In a travel-diary style, Peat writes that he wanted to get away from the narrow streets of Papeete, the small city on the northwest coast of Tahiti that serves as the capital of French Polynesia, and get out into the woods. So he took an old, smoke-belching bus 15 km east out of town along the coast. He got off and walked 2 km to reach the famous point where Cook and the scientists on the expedition had set up their astronomical instruments. Peat summarizes the reactions of the Tahitians to the Europeans as wariness about the firepower on the three-masted vessels, though at the same time the local people were intrigued by the visitors.

Cook and his expedition arrived in the ship Endeavor on April 12, 1769, seven weeks ahead of the transit date calculated by the European scientists. So Charles Green, the astronomer on the expedition, had a fort constructed around the observatory to protect it from curious Tahitians. He posted an armed guard as added protection but nevertheless one day a quadrant disappeared. Green and the chief scientist with the expedition, Joseph Banks, gained some information from a chief and they quickly traced the missing equipment to a village 6 km away.

On May 20, still two weeks ahead of the transit, the Tahitians celebrated with feasting and rituals an astronomical event of their own when the constellation Pleiades, known by the local people as Matari’i, sank below the horizon. That event, to the people of Eastern Polynesia, represented the beginning of winter and a time of food scarcity.

During these events, the two artists who accompanied the expedition, Sydney Parkinson and Andrerw Buchan, were busily recording in their works the scenes around the bay: people, their dwellings, landscapes, vessels, plants, and so on.

Dawn on June 3, 1769, was clear. The scientists were able to see and record the transit of Venus across the sun, a tiny black dot that appeared to move across the surface of the solar disc. However, they were not able to track it as precisely as they had hoped because of interference from the atmosphere of the planet.

The Point Venus observatory and its surrounding fort are completely gone now but one hundred years after Cook’s adventures on Tahiti, a lighthouse was built at the point. Other historical markers have since been added to the park. Mr. Peat completed his tour of Point Venus, observed other visitors in the park, and returned in the afternoon heat to Papeete.