Several Semai spoke up at a political convention in a major Malaysian city last week to complain about the lack of services provided by the state for their villages. A report in the news service The Malaysian Insight described the ways the state of Pahang has been ignoring its Semai communities.

After 60 years of government in the state by the Barisan Nasional (BN), a leading political party throughout Malaysia, a convention in the state capital, Kuantan, of another party, the Pakatan Harapan, provided the venue for the expressions of Semai impatience. Several Semai from communities in the Cameron Highlands spoke up for their rights.

Singgol Oleh, a 43-year old man from Kampung Tual, complained about the fact that some Semai ancestral lands in the Cameron Highlands have been gazetted as permanent forest reserves. “This means that the land belongs to the Malaysian government,” he said to the roughly 200 people in the audience. “It also means we have lost our customary land, and our identity as natives is threatened.”

He expressed his fear that their children may be deprived of their homes so they will be unable to take shelter or to feed themselves. He said the community is afraid that future generations will lose their identity because of the loss of their ancestral property. “This has to change,” he said, adding that he hoped a new government would allow the Orang Asli (Original People) to return to their traditional lands. A community center designed especially for the young people in Kampung Tual is attempting to keep alive the Semai culture through its innovative programing.

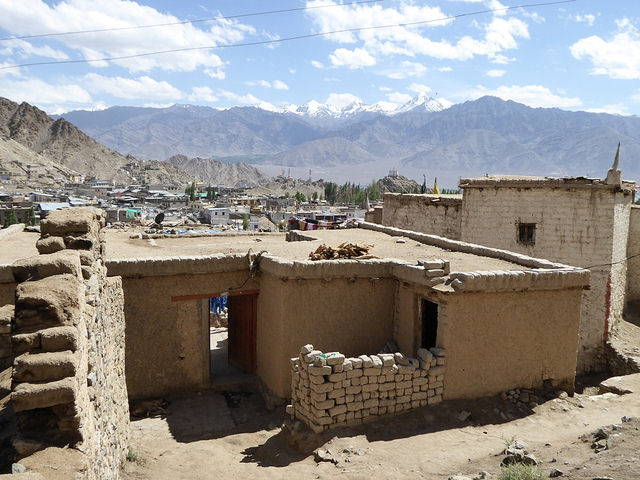

Zainal Kaptar, from a different village in the Semai community of Pos Sinderut, complained about the fact that the lack of electricity makes it hard for their children to study after dark. He told the audience, sarcastically, that Malaysia could hardly claim to be an advanced country, despite all the luxury hotels and skyscrapers in the cities, when Semai villages lack electricity.

Furthermore, some Orang Asli villages are cut off when the rains produce mudslides that close the roadways. “There is a stark difference between the infrastructure given to the Orang Asli compared to other races. Why does this difference exist? Aren’t we Malaysians too?” Zainal asked rhetorically.

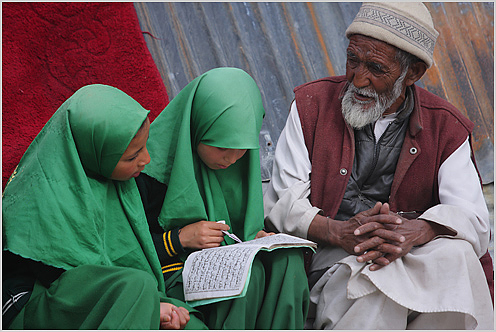

Norhadi Nordin, a 25-year old from the same town, Pos Sinderut, spoke about the difficulty that some Semai young people experience in trying to get an education. He said that there is only one primary school in the community and that some pupils, even after six years of schooling, are unable to read, write, or count properly. He told The Malaysian Insight on the side of the convention hall that their village leaders had spoken to the school authorities a couple times but their appeals had been ignored.

Norhadi added that it is hard for the Orang Asli young people even to get accepted into vocational colleges. He hopes that future governments will take the education of the Orang Asli children more seriously.