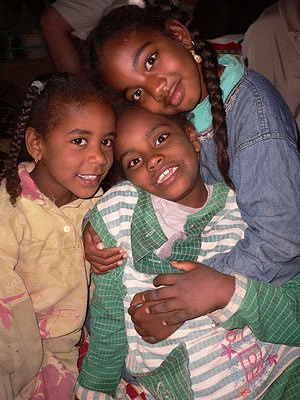

The agricultural productivity of the Ufipa Plateau in southwestern Tanzania may have helped prompt the Fipa in the region into forming a peaceful society. That was one of the conclusions reached by Roy Willis in his 1989 article “The ‘Peace Puzzle’ in Ufipa.” Because of its intriguing analysis of that society, the article is included in the Archive of this website.

Willis carefully described the agriculture he saw when he did his fieldwork among the Fipa from 1962 to 1964 and again in 1966. He noted that a staple crop in the Rukwa Region of that country, where the Ufipa Plateau is located, was finger millet. The people also kept cattle, sheep, goats, chickens, and pigeons, and the farmers displayed their social status by the numbers of cattle they owned.

Prof. Willis argued that since the region is virtually un-forested, slash and burn swidden agriculture could not be used. Instead, the Fipa developed a raised bed compost technique for the production of their food. Their agriculture was perhaps six times as productive as that of the other Bantu-speaking farmers in surrounding regions, but the Fipa had to live in stable villages in order to practice their farming properly. Their peaceful “culture of intense sociability,” as Willis described it (p.134), may have developed as a result of that stable, effective, and productive farming practice.

In late April of 2011, an article in AllAfrica.com, which was described in a news report on this website in early May that year, analyzed the farming practices of the Rukwa Region of Tanzania, an update from the piece by Willis. That article quoted the then Regional Commissioner, Mr. Daniel Ole Njoolay, as saying that the people of the Rukwa Region “are born seeing parents and other members of the family work hard in the farms and they grow up that way. So this is passed on from one generation to another.”

Last week, the same source published an update—a news analysis of the incredible fertility and growing farm potential in the area. The author of the current report, Sosthenes Mwita, does not mention the raised bed farming of the 1960s, but he does declare that the Rukwa Region could become the breadbasket of all Tanzania. It has plenty of rainfall—between 800 and 1,200 mm. per year—but it needs help in developing its farming infrastructure in order to realize its rich potential for more agricultural production. He writes that 90 percent of the economy is based on agriculture; 34 percent of the region is arable, but only about one-quarter of that is under cultivation.

The writer lists the food crops being grown by farmers in the region, which include finger millet, wheat, sorghum, sweet potatoes, cassava, maize, and beans. Farmers also grow groundnuts, tobacco, sunflowers, cotton, coffee, and soya for cash. During the recent farming season, farmers harvested over one million tons of food crops on 529,545 hectares of cultivated land. Farmers earned close to two billion Tanzanian shillings (over US $900,000) in the past couple years from growing tobacco alone.

Mr. Mwita writes that the Rukwa Region has considerable potential for increasing its agricultural production if more land were to be irrigated. About 68,000 hectares in the region are considered to be very well suited for irrigation, according to one report.

One difficulty in further developing agriculture in the Rukwa Region is that very little of the additional arable land is located within reasonable walking distance of the villages. The region is dominated by small-scale subsistence farming, much as it was when Willis was there. Most of the tilling work, about 75 percent, is done with plows pulled by oxen or donkeys. Weeding is mostly still done by hand with hoes. The farmers in the region have very few tractors.

Numerous other factors also hamper the development of agriculture, such as inadequate banking facilities offering few agricultural loans. Also, there are not enough good storage and processing facilities in the region, which sometimes results in the degradation and loss of harvested crops. The author speculates that if companies were to invest in agricultural processing, crops such as finger millet, sunflowers, groundnuts, and others could become much more profitable.

Another factor that limits the growth of the agricultural sector in the Rukwa Region is the absence of good roads. Most of the highways are unsurfaced, which severely limits transportation. Furthermore, farmers lack the capital to improve their means of production. They do not have the resources to purchase farming equipment, so they continue to rely on their animal power, Mr. Mwita indicates.

Despite the detailed descriptions of the benefits to be derived from improving the farming infrastructure in the Rukwa Region, it is not clear whether such improvements would help preserve the traditional peaceful social structure of the villages in Ufipa.