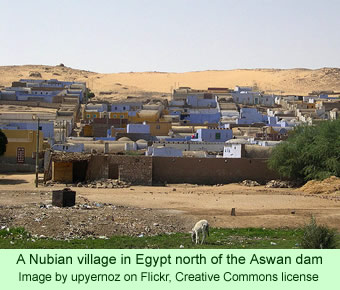

Ever since the completion of the Aswan High Dam in 1964, successive Egyptian governments have ignored promises made to the Nubians that they would be allowed to return to farming villages along the Nile. For 51 years, the Nubian people have cherished the promise—the hope—of returning to the peaceful ways of their rural villages.

Last week, Al-Monitor, a prominent, Web-based, news and analysis service focusing on Middle East issues, carried a story by reporter Khalid Hassan on the right of return issue and its continuing importance for many Nubians.

Last week, Al-Monitor, a prominent, Web-based, news and analysis service focusing on Middle East issues, carried a story by reporter Khalid Hassan on the right of return issue and its continuing importance for many Nubians.

He begins with the facts and figures. The dam is massive: over 2.3 miles (3.83 km.) long, 131 feet (40 m.) wide, and 364 feet (111 m.) high. It generates 10 billion kilowatt hours of electricity per year. But to achieve that, over 135,000 Nubians had to be evicted from their homes more than 50 years ago and resettled into new communities, many with inadequate homes that lacked roofs.

The journalist reports that at a Nubian sit-in on July 10, they decried the racism that they feel persists in the broader Egyptian society. “I am a Nubian and I am proud,” a sign said at the demonstration. The demonstrators made many demands: the need to teach Nubian history in Egyptian schools; the criminalization of public racism.

Hassan visits Nubians in their communities and interviews a number of them in order to convey their thoughts and feelings. He talked with Nader Ibrahim, a 72 year old man who was just 20 when he was forced to leave his village. His bitterness comes through in the interview. After describing the eviction and the false promises, he joined the Egyptian armed forces, served during the October War as a translator, and was awarded a medal for his work. Then he was left to take care of himself, without any shelter or community to return to.

Mohammad Hamed, a brigadier general and former Member of Parliament, castigated all of the governments of Egypt since 1964 that have allowed the Nubians to be marginalized, to be viewed by the majority society as non-Egyptians. Ashraf Osman, the head of the Nubian Supreme Council, pointed out that the current national constitution guarantees the right to return. The inaction of the present government in that matter is therefore contrary to the constitution.

Badr al-Din Chellali, from the Egyptian Democratic Party in Aswan, said his group submitted a draft law to the Ministry of Transitional Justice 11 months ago to help resolve the situation. It contains 25 articles about the right to return and resettlement of Nubians on the banks of the river. So far, the ministry has not responded and refuses to say why.

Mr. Hassan, the reporter, went to the ministry himself to find out why the delay. Fatima Siraj, a member of the committee that had been charged with drafting the law about the right of return, told him, “the ministry made all efforts for the return of the Nubians, and we recognize their rights of return to their areas of origin.” After the committee had several sessions consulting with the Nubians to hear their demands, the draft law was now finished, she said.

It provides for the return of Nubians to the areas where they originated, and the development of villages for them. The government is determined to give them what they want. The holdup? The government is waiting for a newly-elected parliament to approve the draft law. Parliamentary elections got underway in Egypt on Sunday, October 18.