Curiosity about the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic to the peaceful societies led to a news report in a major Indian newspaper on April 10 which indicated that as of that date Sikkim had not yet reported any cases of the coronavirus. Sikkim, a small state in northeastern India, is the home of the Lepcha people. All of India is coping with the pandemic by lockdown orders from the national government.

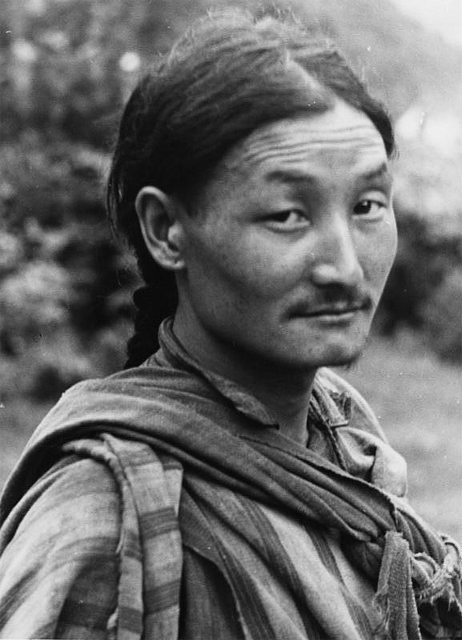

A more informative piece about the ways the Lepchas are handling the crisis appeared in a different news story the next day, April 11. That report indicated that they are turning to their traditional religious practices for support. Olley Lepcha, a bongthing, their term for a traditional priest, performed appropriate rituals in his village, Naga, in North Sikkim, a district with a lot of spectacular scenery. His rituals sought to expel the coronavirus demon and keep Sikkim, the rest of the Himalayas, and all of India safe from the aggressive disease.

The news article goes on to report that the bongthing is the head of a school for bongthings located in the village and that his students helped him perform the “wonderful ritual.” He chants, offers prayers, and performs rituals to help people cope with various social issues and calamities. The bongthings, the article concludes, are traditional healers who appease the gods and chase away the demons that cause the suffering of humanity.

More information about bongthings turns up in the literature on the Lepchas. These priests of their faith, referred to as “Bon” or “Bone,” are representatives on earth of the Mother Creator. The bongthings used to be present at all Lepcha rituals to appease the demons and gods and make proper offerings. The shamans retain all the sacred knowledge of the people and they serve as the keepers of Lepcha culture and tradition.

The virtual disappearance of the shamans in recent times is one of the major factors that is causing the abandonment of the Lepcha’s localized knowledge and ritualized life, which is weakening their society and culture. A news story from November 2011 indicated that the performance of the rituals at Mount Kanchenjunga would soon be lost since the bongthing there, Sandup, had discontinued performing them in the mid-1970’s. In fact, the rituals were preserved, recorded by the Danish scholar Halfdan Siiger, who had gained the confidence of Sandup’s father, the previous Kanchenjunga bongthing, in 1956. The elder priest had allowed him to record the rituals.

The rituals that Samdup used to perform at Nung, his village, were the basis for Lepcha nationalistic pride. Other bongthings also offered rituals to Kanchenjunga, but the one at Nung was the most important. The secret ritual, and its accompanying processional song, would now be lost except for the recording that Siiger made and transcribed into his book The Lepchas: Culture and Religion of a Himalayan People.

The gradual influx of Buddhism into Sikkim had begun to dilute the Bon nature worship several hundred years ago. The annual Kanchenjunga rites at Nung were the strongest surviving relics from that earlier era. The bongthing from Nung used to process to the seat of Sikkim power, the capital at Gangtok, where the Chogyal, the Buddhist king, would honor him with many gifts and a symbolic yak, obtained from much higher mountains. The bongthing would take it all back to the altar at Nung with great ceremony.

So while the bongthings now may not be much involved in grand ceremonies, it is interesting to learn that in these times of great stress, a low-key, peaceful society such as the Lepchas can still turn to their traditions for help. And that at least one surviving priest and his students will respond.