“Among individuals, as among nations, respect for the rights of others is peace,” wrote the great Zapotec president of Mexico, Benito Juárez. Wendy White Polk opined in an El Paso blog post last week that a lot of Americans, as well as many Mexicans, have been influenced by the wisdom of that famous president and national leader.

Ms. Polk, celebrating the memory of Juárez, compares him to Abraham Lincoln. The two presidents were contemporaries in the 1860s, and Juárez has a stature in Mexico comparable to Lincoln’s in the U.S. Both leaders were born into humble circumstances, Lincoln in a log cabin in Kentucky, Juárez in a rural Zapotec Indian village in the state of Oaxaca, in southern Mexico.

Ms. Polk, celebrating the memory of Juárez, compares him to Abraham Lincoln. The two presidents were contemporaries in the 1860s, and Juárez has a stature in Mexico comparable to Lincoln’s in the U.S. Both leaders were born into humble circumstances, Lincoln in a log cabin in Kentucky, Juárez in a rural Zapotec Indian village in the state of Oaxaca, in southern Mexico.

Appropriately enough, Juárez and Lincoln maintained relationships of respect with one another during their respective presidencies, and they supported each other on several occasions. Lincoln sent Juárez a message in 1861 saying that he hoped “for the liberty of .. your government and its people.” In return, Juárez refused to recognize the Confederacy during the American Civil War, and Lincoln supported Juárez in his war against France, which had invaded Mexico and captured Mexico City in 1863.

Both leaders have been memorialized with many statues, though not all are situated in their own countries. The Mexican cities of Ciudad Juárez, directly across the Rio Grand from El Paso, and Tijuana have statues of Lincoln. Similarly, there are statues of Juárez in Chicago, New York, and Washington, D.C. El Paso has not had a monument to the Mexican president, though one is in the works, which is the purpose of Ms. White’s blog post.

Sculptors John Houser and his son Ethan Houser have been working on one, and they visited El Paso to unveil a clay model of the statue they hope to complete for Juárez. Instead of a grandiose monument, with the hero perched high on a commanding pedestal, they plan a statue that will be only slightly larger than life. Juárez will be portrayed sitting on a bench next to a boy, who turns out to be the president himself as a youngster.

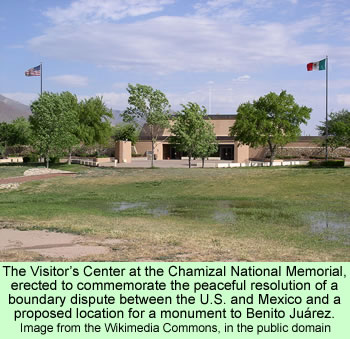

The design is intended to allow visitors to sit beside Juárez and have their pictures taken next to him. As long as funding is made available, the sculptors feel it will take about a year and a half to produce the final bronze sculpture. They hope that the statue will be installed at the Chamizal National Memorial, an urban park in El Paso that commemorates the peaceful resolution in 1963 of an international border dispute between Mexico and the U.S. that had stretched back for a century. It sounds like a fitting spot for a monument to Juárez.

Ms. White’s blog post includes contact information for those who would like to contribute to the costs of the Juárez monument in El Paso.

On July 9, 1993, Pauline Browes, at the time Canadian government minister for Indian and Northern Affairs, flew to Coppermine, now known as Kugluktuk, to attend a ceremony and proclaim that the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement was officially in effect. The agreement had been signed by then Prime Minister of Canada Brian Mulroney six weeks earlier in Iqaluit.

On July 9, 1993, Pauline Browes, at the time Canadian government minister for Indian and Northern Affairs, flew to Coppermine, now known as Kugluktuk, to attend a ceremony and proclaim that the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement was officially in effect. The agreement had been signed by then Prime Minister of Canada Brian Mulroney six weeks earlier in Iqaluit.