A Tahitian news source reported last week that two different men had assaulted two different women, one in Papeete and the other on the normally more peaceful island of Huahine. Both women filed complaints with the police.

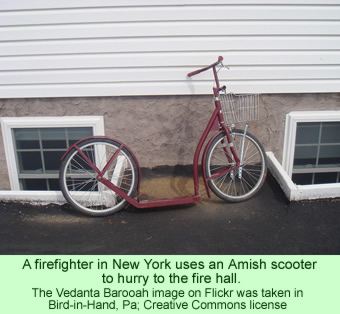

The details serve to challenge the idea that the Tahitians are still able to maintain a peaceful society, so they need to be examined. In Papeete, the capital of French Polynesia on the island of Tahiti, at 7:00 AM on Sunday, October 26, a young couple, both about 20 years of age, returned to a motor scooter after spending a night drinking. As they were driving off, the woman, who is pregnant, complained to the man that she had stomach pains and they needed to stop.

The details serve to challenge the idea that the Tahitians are still able to maintain a peaceful society, so they need to be examined. In Papeete, the capital of French Polynesia on the island of Tahiti, at 7:00 AM on Sunday, October 26, a young couple, both about 20 years of age, returned to a motor scooter after spending a night drinking. As they were driving off, the woman, who is pregnant, complained to the man that she had stomach pains and they needed to stop.

He refused. The woman somehow got him to stop, climbed off the scooter, and sat down nearby due to her pains. The man became angry and started assaulting her. Fortunately, some bystanders witnessed the scene and intervened to protect her. They took her to a hospital. An hour later, she went to the police and filed a complaint. They quickly found the violent drunk and arrested him. He was to appear in court on Monday the 27th.

Meanwhile, on the nearby island of Huahine, the same news report indicated that a woman also filed a complaint with the police there about a man assaulting her. The vahine (Tahitian for woman) was not seriously hurt, but she filed her charges anyway against the tane (Tahitian for man). He too will have his day in court.

A different Pacific news source published a few days later repeated the same stories, but it added more information about how the Tahitians are trying to cope with the growing problem of domestic violence. It focused on a meeting of a group formed to try and combat such violence, called the L’Association Utuafare Mataeinaa.

The President of the association, Alexandra David, called a meeting on Friday, October 24, with stakeholders from other organizations and agencies involved with the issue. The meeting was held at the municipal building of Taravao, a rural community on the island of Tahiti. Ms. David wanted, first, to describe the activities of the association, such as their information campaigns with the general public and their outreach in the schools that seek to stem domestic violence.

The voluntary association has also become active in trying to help the victims of abuse and assault, she said. The discussion turned to the realization that this sort of violence sometimes results in suicides. Henry Perry, the president of a suicide awareness group called SOS Vie, said that three suicides had occurred recently. He referred to suicides as a plague.

Participants at the meeting agreed that in many situations, victims may need assistance in searching for jobs or housing. They may need moral or financial help in order for stability to return to their lives. Everyone agreed on the importance of promoting mediation among couples struggling with violence. Ms. David called for the participants to work together in caring for the victims of abuse as well as their families.

Robert I. Levy provided some useful background on this sort of violence. He wrote that the Tahitians were able to release hostilities that they may have felt toward their spouses, but they did it safely, without harming anyone. The prominent anthropologist did field work from 1962 to 1964, both in Papeete and in a village on Huahine that he referred to as Piri. He wrote (1969) about the ways Tahitian men and women interacted 50 years ago.

Even when they drank, Levy indicated, the Tahitians did not normally act more hostile than at any other time, at least when they were in public. The only time when violence did occasionally occur was during private drinking sessions at home, when fights sometimes did break out. In his 1969 article, Levy added some useful information about the ways the Tahitians, at least in the two communities he studied, conceived of anger—which of course is a major factor in promoting domestic violence.

Levy wrote that the Tahitian word for anger is riri, a feeling that arises in people, they believe, in the abdomen. Once this feeling arises, it is thought over in the head as feruri. They have other words for rage, irritability, and the like, and an examination of 301 words for states of feeling in an early Tahitian dictionary showed that 47 referred to anger, though that number since then has dropped.

Anger is always viewed as bad in Tahitian, Levy reported. Some words have double meanings, such as “to beat up” also means “to kill,” and the word for “unconscious” also means “dead.” He wrote that the Tahitian language did not distinguish a statement such as “He will get mad and beat up somebody” from what, in other societies, would be considered a very different statement: “He will get mad and kill somebody (p.370).” Thus, expressions of violence—to beat up someone—carry the anxiety that the action may get far out of hand.

The Tahitians felt, at least in Levy’s time, that anger needed to be expressed through angry words. One man told Levy, “The Tahitian people say that an angry man is like a bottle. When he gets filled up he will begin to spill over (p.371).”

However, Levy did note in another work (1973) that in Papeete, the urban environment put special stresses on the traditional patterns of nonviolent social life. The challenges of modernity, he wrote, “have dislocated the sense of balance and [sexual] equality striven for in places like Piri (p.237).” It is clear from the news last week that the traditional feelings of equality are much weaker today, but that at least some Tahitians are attempting to deal pragmatically with the continuing problem of domestic violence.

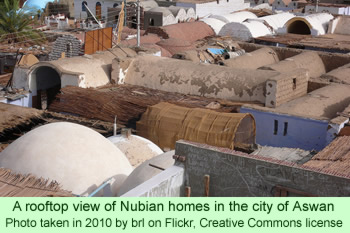

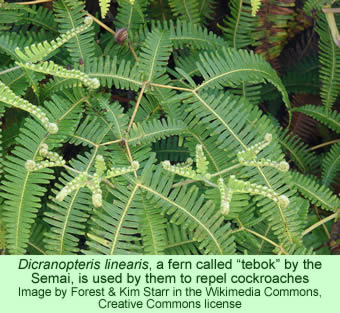

The project was carried out in Kampung Batu 16, a village of 28 households with a population of 278 people at the time of the study. It is located in the Malaysian state of Perak. (The “16” refers to the fact that the village is near the 16th mile marker along a road.) The village consists of houses located on a slope above a river, though they are not too near it to avoid the dangers of high water. The houses are built in what the authors term the “native style,” that is, constructed mostly from plant materials obtained from surrounding forests.

The project was carried out in Kampung Batu 16, a village of 28 households with a population of 278 people at the time of the study. It is located in the Malaysian state of Perak. (The “16” refers to the fact that the village is near the 16th mile marker along a road.) The village consists of houses located on a slope above a river, though they are not too near it to avoid the dangers of high water. The houses are built in what the authors term the “native style,” that is, constructed mostly from plant materials obtained from surrounding forests.