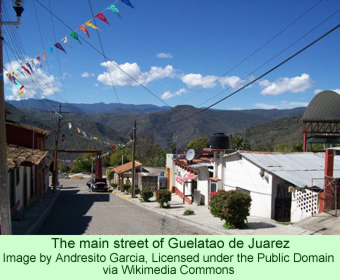

The Zapotec woman spoke insightfully: “I feel that we have deep roots as an indigenous town, which has changed over time, it’s true, but [it] is still very rooted in our values, in solidarity, brotherhood, in community work.” Carmen Alonso Santiago, director of the Zapotec NGO Flor y Canto (Flower and Song) in Mexico’s Oaxaca state, added that their culture is transmitted through education, and that women are the major teachers.

Ms. Santiago was quoted extensively in a lengthy article last week in Truthout.org, the latest in their series of articles on the indigenous people of the state, with a special focus on the Zapotec. A piece last month described the ramifications of the traditional, indigenous social and political system in Oaxaca called “uses and customs.” The current article extends that analysis to explore the effects of emigration, primarily of male workers to the United States, on the people left behind in the indigenous communities of Oaxaca. That is, the effects on women of the absence of many men.

Ms. Santiago was quoted extensively in a lengthy article last week in Truthout.org, the latest in their series of articles on the indigenous people of the state, with a special focus on the Zapotec. A piece last month described the ramifications of the traditional, indigenous social and political system in Oaxaca called “uses and customs.” The current article extends that analysis to explore the effects of emigration, primarily of male workers to the United States, on the people left behind in the indigenous communities of Oaxaca. That is, the effects on women of the absence of many men.

The figures the article opens with are startling. Oaxaca has a population estimated at 3.1 million; 2 million people from that state live in the U.S. The majority of the emigrants from the state come from indigenous communities and they work as laborers in industries such as agriculture, construction, restaurants, and domestic service. About 98 percent of the emigrants work in the U.S., especially in California, Arizona, and Texas.

The reason that the men leave is to find work so they can send remittances back to their home communities and support their families. Oaxaca is second from the poorest state in Mexico, and while migrants from the state have been moving north since the 1960s, the North American Free Trade Agreement, which went into effect in 1994, made matters worse for the indigenous communities. Imported corn became cheaper than the locally-grown grain, undercutting the local farming economy and resulting in the partial abandonment of the rural countryside.

The thrust of the current article is to explore the effects of this economic transformation on rural, Zapotec society, particularly on the social lives of the women with the men largely gone. Ms. Santiago argues that it is the cargos—the voluntary responsibilities assumed by citizens within the uses and customs system—which the women are assuming in the absence of men that is altering the gendered nature of their society. The departure of the men is forcing the women to assume greater obligations, but it is also offering them more opportunities to strengthen their roles in their communities.

Truthout interviewed Pastora Gutiérrez Reyes, a woman who has been a leader in the Zapotec town of Teotitlán del Valle for many years. Lynn Stephen devoted several pages in her book Zapotec Women (2005) to a portrayal of her, and the current news report provides an update on Ms. Gutiérrez Reyes’ perceptions of the roles of women in the community, which is very well known for its weaving.

Ms. Gutiérrez Reyes describes graphically how the women coped, as wives and widows of men who had emigrated, by forming a cooperative group called Vida Nueva. Even the boys were leaving as soon as they finished middle schools, she said. “Our group formed as a way to find options for work. That’s how we started to work in the fields and to weave.”

Gutiérrez Reyes describes how one thing led to another. At first, the point of the cooperative was to help the women get fair prices for their weavings but it led to their working together to promote other common concerns: opposition to drug use, health issues, sexuality, and self-esteem. She tells the journalists that a lot has happened in the 17 years since the formation of the cooperative.

At the beginning, the women received a lot of criticism from the men, just for organizing the cooperative. Her spunk comes through clearly in this current article: “Can you imagine a group of women organizing ourselves 17 years ago? Women couldn’t even leave the town,” she says.

She continues by relating how the women have gradually taken initiatives in Teotitlán del Valle, pressuring the male authorities to allow them to participate in the assemblies. As some women began to participate, others saw what they were doing and decided to try and take a more active role in the town also. She says that the women whose husbands are away, or deceased, tend to be the most active, and she seems proud that they are now invited to official or political events by town leaders.

Furthermore, women now can assume the voluntary cargos. More than that, the men in Teotitlán are seeing positive results of the growing activity of the women, and they are accepting it. Today, Gutiérrez Reyes concludes, “there is a little more equality.”

Ms. Santiago cautions that the situation in one Zapotec town should not be generalized to others, for the conditions of indigenous women vary widely. The reason is that the uses and customs vary from one town to the next. In some, women are still not permitted to run for political office, while in others they are. In some, women are not allowed to speak out in the municipal assemblies, but in others, they not only vote, they participate.

The investigation by the authors bears out her contention. A publication from the National Human Rights Commission of Mexico indicated that of the 361 municipalities in Oaxaca that governed themselves by the uses and customs conventions, 62.7 percent allowed women to vote, but 15.8 percent did not. In others, only married women, or only single women, or only widows could vote.

Truthout summarizes the situation: women are slowly taking roles in their communities, but more as members of committees than as leaders in official positions. One prominent exception cited by the article is Eufrosina Cruz Mendoza, the young Zapotec woman who was elected to a local political office in 2007 but the male authority figures in her town vetoed the election results because she was a female, an action that received widespread publicity. She is now serving in a prominent state office as the President of the Directive Body of the State Congress of Oaxaca.

This excellent Truthout.org article concludes with more wisdom from Ms.Santiago, who says that, within the well-defined cultural roles of the traditional Zapotec communities, “It is [the] women who are pushing a process to raise their level of participation.”

Bessi, Renata and Santiago Navarro F. 2014. “As Men Emigrate, Indigenous Women Gain Political Opportunities and Obligations in Mexico,” translated by Mirriam Taylor. Truthout (Monday, 18 August).

Signe Howell describes the Chewong concepts of reality in the forests of Peninsular Malaysia in an essay she included in the work The Handbook of Contemporary Animism, published last year in the UK. She analyzes the role of animism in their society, which is at the center of their system of beliefs. Her explanation helps clarify why the Chewong are so highly nonviolent.

Signe Howell describes the Chewong concepts of reality in the forests of Peninsular Malaysia in an essay she included in the work The Handbook of Contemporary Animism, published last year in the UK. She analyzes the role of animism in their society, which is at the center of their system of beliefs. Her explanation helps clarify why the Chewong are so highly nonviolent. Sharma did her field research in the Dzongu Reserve in northern Sikkim, the heartland of Lepcha country, from September through November 2003. One major topic she reviews is their traditional approaches to resolving conflicts, and the ways they handle disputes today.

Sharma did her field research in the Dzongu Reserve in northern Sikkim, the heartland of Lepcha country, from September through November 2003. One major topic she reviews is their traditional approaches to resolving conflicts, and the ways they handle disputes today.